News and Articles › Cave of Apelles

The imitation of beautiful nature becomes kitsch, because physics as embraced by infinite subjectivity cannot be imitated by thesis, by artifice, or by technology.

— Agnes Heller, philosopher

Top list

View the entire list

Vegard Martinsen guests this month’s Cave of Apelles. Martinsen is an author and lecturer belonging to the Objectivist field of thought. He has written several books and articles on Ayn Rand’s philosophy and the influence of Immanuel Kant.

In this episode, Jan-Ove Tuv and Martinsen discuss how Ayn Rand and her Objectivist philosophy offers an alternative to the Kantian aesthetics.

While Immanuel Kant values a disinterested approach to art and the artist’s spontaneous originality, Ayn Rand emphasizes how painting, sculpture, music, but primarily how literature portrays an ideal to strive for, as well as the importance of an eternal perspective.

– The only major figure that is not Kantian is Ayn Rand, says Martinsen and elaborates:

– That is why people look down upon her and why she has this difficulty in getting through to be regarded as a serious philosopher, because she does not share the Kantian basic standpoint. She is completely non-Kantian. In a field and culture where Kant rules everything, of course it is difficult to get on the inside.

Would you like to be credited as a supporter in future videos?

Donate now

Immanuel Kant is everywhere

Martinsen initiates the conversation by explaining the basis of Kant’s philosophy.

– Kant says that we cannot really know anything about what really exists. We can only know what it looks like for us, says Martinsen and continues:

– If we cannot know reality, we cannot know anything.

Jan-Ove Tuv remarks that such a mindset results in the situation we see today, where people say “You cannot learn art”.

– Empiricism, says Tuv, has been completely discredited.

Martinsen agrees and adds:

– And this leads to subjectivism, where people say “It may be true for you, but it’s not true for me”.

Vegard Martinsen, interviewed by Jan-Ove Tuv. Photo: Cave of Apelles

Tuv asks Martinsen how Rand goes about to rectify the influence of Kant. Martinsen replies that Rand was a system builder, creating a system of philosophy. He explains it as follows:

Epistemology: Rand bases her epistemology on the senses and reason alone with no opening for faith, intuition, or revelation.

Ethics: Rand has a pure egoistic ethics: You have one life, live it well by being honest and productive, and do not initiate force.

Politics: Rand recommends pure unregulated capitalism: The government should do only the police, the courts, and the military – nothing else.

Aesthetics: Art is, according to Rand, a selective recreation of reality in accordance with the artist’s metaphysical value judgments.

Previously: Learn How to Paint From Daoism

The Romantic Manifesto

Most of Rand’s aesthetic theories are presented in the book The Romantic Manifesto, which was published 50 years ago.

Tuv asks: – Why does she use the term “romantic”?

– There was a period in the 19thcentury, where you had writers who were called romantic. She defines this school of writing more fundamental than other writers, answers Martinsen explaining that the romantic school put weight on the emotional state of the characters.

Ayn Rand was inspired by Aristotle and his Poetics when she wrote The Romantic Manifesto.

But Rand is more fundamental, according to Martinsen, stating that Rand focuses on volition.

The focus on volition is important, according to Rand, because the artist’s philosophical value judgments is “pushed” into the work. When you paint something, Martinsen explains, you paint “this is how I see the world”.

– The most respected and admired author in the world today is William Shakespeare. […] In his plays, there’s no connection between how good and moral the persons are and how their fate turns out during the play, says Martinsen and elaborates:

– Shakespeare is a nihilist. That is why he is so popular today – because we have a nihilist culture.

As an opposing example, Martinsen points to Victor Hugo, whose characters are good people doing the right thing. Not coincidentally, Hugo was Rand’s favorite author.

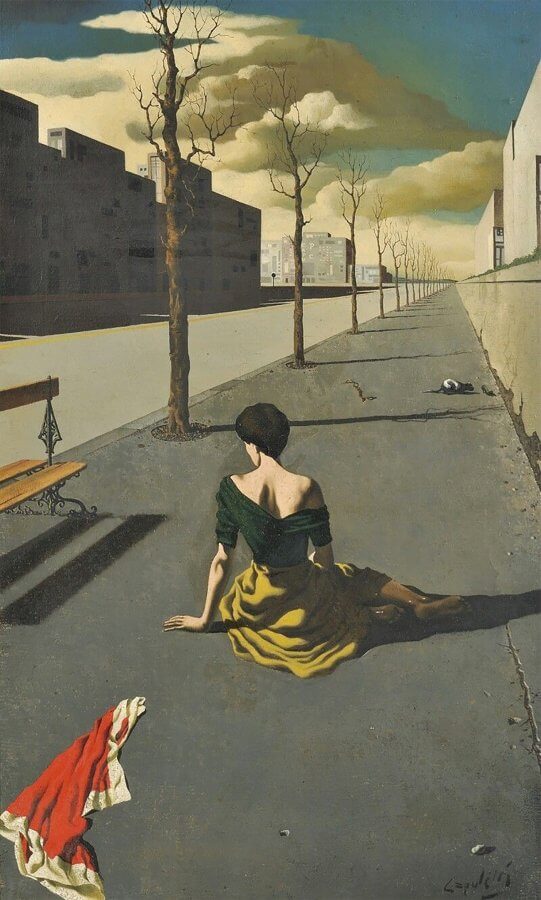

Jose Manuel Capuletti: Le Dernière Heure, Oil on canvas, 43 x 30 in. (109.2 x 76.2 cm). Capuletti was Ayn Rand’s favorite contemporary painter. Photo: Skinner

The Importance of Art

– We need art because every human being has a philosophy. But philosophy is a big and abstract thing, and we need something that can keep this philosophy as an object, almost. We need art because it concretizes philosophy and keeps our philosophy alive. Without art, we couldn’t keep our philosophies alive, says Martinsen and argues that Hegel’s argument saying that maybe it will come to a society where people no longer would need art, is “complete BS”.

Ayn Rand defines art as “a selective recreation of reality in accordance with the artist’s metaphysical value judgments.” Tuv encourages Martinsen to explain this somewhat complicated definition.

– Metaphysics is about the fundamental, most basic elements of reality, and an artist has an idea of what reality really looks like. For instance: Is it possible to achieve happiness? Should I follow my own wishes? Does God exist? Everybody has an opinion on matters like these. These are metaphysical questions, says Martinsen and continues:

– What a painter or author does is that he includes these things in his paintings in order to show that if he includes them in his work, they are the important things to him. And you, as the reader or the person who looks at the painting, should consider these things.

– You mentioned the term “sense of life,” and I think that is such a beautiful term, says Tuv, before giving an example:

– The Greek Hellenistic figure is a good illustration of the view of man that Ayn Rand wants to see more of. “I know I’m good and I will treat you with respect” – that’s the kind of hero Ayn Rand is after!

Bronze cast of an ancient statue of the Greek god Dionysius. Photo: Cave of Apelles

The Ideal to Strive For

Tuv and Martinsen discuss an aspect that Rand borrows from Aristotle, namely that fiction is more important than history because history deals with particulars, while fiction or poetry deals with universals, that is to say how things could be and ought to be.

Jan-Ove Tuv points out an argument by Rand that impressed him: she talks about how romantic art is criticized for being an escape from reality, but then she eloquently turns the point, saying that romantic art gives an ideal to strive for.

Continuing this line of thought, Tuv asks: – What is the difference between romanticism and naturalism?

Martinsen answers: – Romanticism, Ayn Rand said, focuses on that people have free will. […] In naturalism, people don’t have choice. They are just poured in the circumstances. What happens around them influences them in major ways, and they don’t choose.

– A major problem with the naturalist works is that there is no lust for life, no drama, argues Tuv and points to the paintings by Lucien Freud, who portrayed lifeless, indifferent characters.

– There’s no ideal. There’s nothing to enjoy. Just some horrible sight, adds Martinsen.

Clarifications

Although Tuv is impressed with Rand’s philosophy, there are some areas in her aesthetics he finds problematic.

For one, Tuv finds it odd that Rand seemingly argues against the inclusion of “ugly” aspects in a painting. Considering her emphasis on narrative, he points to her example of painting a pretty woman with a mouth sore.

– In reality, a cold sore doesn’t mean anything, answers Martinsen, but why has the artist included it in the painting? I think if an artist includes that, he’s saying: “She is trying to look so nice, but she cannot fight reality.”

– What, then, about Quasimodo?, Tuv asks inquisitively.

– But he is not the only person in the novel, and Hugo has created him because he wants to show that Esmeralda is unavailable to him, says Martinsen.

– So, it’s okay if it has a function in a narrative? asks Tuv.

– Yes.

*

A second point Tuv finds problematic with Rand’s philosophy is her criticism of blurriness in painting. She idealized Vermeer’s (her favorite painter) use of pure colors and pure lines, equating those features with a pure mind and clear thoughts.

– And she criticizes Rembrandt for blurring the outlines and for distortions, because that is sort of irrational, says Jan-Ove, arguing that this argument becomes rather simplistic, almost a bit childish.

Jan-Ove Tuv, from his conversation with Vegard Martinsen. Photo: Cave of Apelles

Tuv elaborates: – I think what she misses are some really fundamental issues. For example, Rembrandt’s blurring is a known technique: To blur outlines, so that you don’t get cutout figures in painting, so that you can get a three-dimensional form, and then the figures become more alive, they can react to each other, and you get a stronger narrative. So she seems to completely fail to understand the function of that technique.

– I don’t know much about painting, but I tend to agree with you. […] I think your criticism is valid, Martinsen answers.

*

Although he is somewhat surprised of Martinsen agreeing completely with his criticism, Tuv presents the last point of disagreement with Rand, namely that of architecture.

Tuv calls Rand’s novel character Howard Roark “the perfect Kant-Hegelian poster boy,” arguing that Roark talks about creating “out of himself, and is concerned with originality, rejecting old formulas.

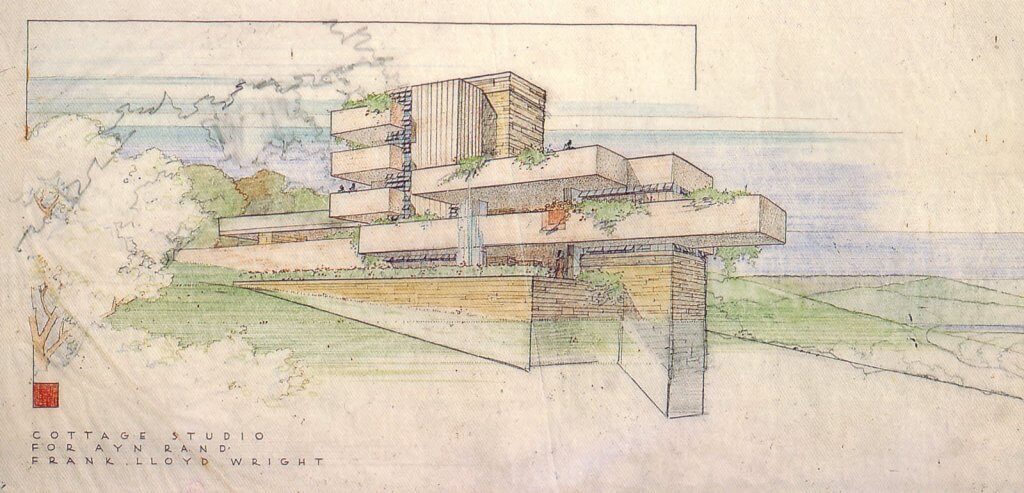

“Cottage Studio” for Ayn Rand (unbuilt), designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright was the main inspiration for Rand’s architect hero Howard Roark in her novel “The Fountainhead” (1943).

– I think the point there is that you should use the technology and the materials available at your time, and not imitate earlier constructions with newer material, Martinsen replies in Rand’s defence.

– Well, this is Kant and Hegel!, exclaims Tuv.

– Well, in that case, they were right. It’s not so that if Kant and Hegel says something, it is necessarily wrong, Martinsen answers.

Tuv argues that Rand’s view of architecture becomes somewhat subjective, as she criticizes large cathedrals because it makes people feel small, while she admires the tall skyscrapers. – It seems like she looks at the symbol behind the building, not the quality of the building itself, Tuv says.

Also read: Why is Ayn Rand so Wrong About Architecture?

Martinsen does not agree:

– The inside of a skyscraper is completely different than the inside of a cathedral. […] You can say that it is an achievement to make both, but the point of the cathedral is to make the man feel small and insignificant, and that’s not the point of a skyscraper.

– What about her point of literature being larger than life – doesn’t that apply to architecture?, asks Tuv.

– Yes, but not so large as a cathedral. Jean Valjean is larger than life, but he is not twenty meters tall. […] The point is that a building should be a place to work and live that fits humans. That it is a good place to be in. And that says something about the size and design and the plane structure. That is what the objectivist theory of architecture is. It doesn’t say that you have to build skyscrapers and you can’t build things that have ornaments. It should fit humans, Martinsen states and continues:

– Taj Mahal is an attempt to create heaven on earth. It’s a beautiful place. I don’t think that’s something an objectivist architect would not have created if you wanted to create something like that.

– Because you can see that as creating an elevated existence?, Tuv asks.

– Yes.

This article was first published at the Herland Report.

Published on Friday, August 16th, 2019