News and Articles › Architecture

Artists now decline to go to bed with beauty, fearing they’ll wake up with kitsch.

— Michael Curran, author

Top list

View the entire list

Ayn Rand is perhaps the greatest philosopher since Aristotle. She put reason on a pedestal and argued that the empiric understanding of reality is paramount. She founded the philosophy of Objectivism, which is best described in her own words:

My philosophy, in essence, is the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute. — Ayn Rand , Appendix to Atlas Shrugged

Objectivism holds that one needs to live by objective principles in order to achieve happiness. This is an important point and serves as the reason for why I have come to the conclusion that there is a serious inconsistency in Rand’s philosophy. That inconsistency is architecture. She wrote a whole novel on the subject called The Fountainhead (1943), which is a great story, rich in characterization. But who is the hero? The modernist Howard Roark who criticizes the flutings on the Parthenon columns because they serve no obvious function.

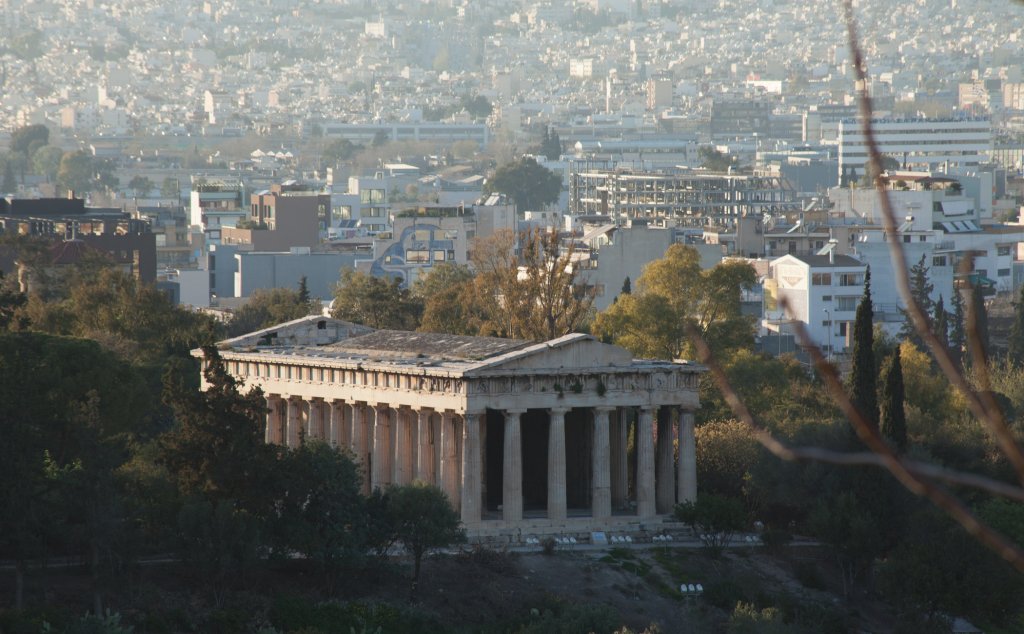

Columns with flutings at an archeological site in Athens, Greece. Photo: Nerdrum Pictures

To be sure, Ayn Rand had a love for almost anything classical. In music there was Rachmaninoff, in literature; Victor Hugo. She was a fervent follower of Aristotle’s Poetics and praised the elevated spirit of the greek statues. She recognized imitation of nature as a vital necessity for great sculpture and painting.

Tragically, nowhere in Aristotle’s surviving texts is there any dedication to the study and understanding of architecture. I call it tragic because of his strong influence on Rand, as well as countless others, and because he certainly would have hailed the supreme position of classical building techniques.

Rand’s modernist shadow

In The Romantic Manifesto, Rand separates architecture from painting, music, literature and sculpture, arguing that “Architecture is in a class by itself, because it combines art with a utilitarian purpose and does not re-create reality, but creates a structure for man’s habitation or use, expressing man’s values.”

This is a peculiar statement and the question one would have to ask is: how do you build a house that does not re-create reality and at the same time expresses man’s values? If the moral purpose of a man’s life is his own happiness, as Rand preached, then he would certainly be more happy with a building that reminded him of — not alienated him from — nature.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water. Photo: Getty Images/Walter Bibikow

To illustrate the issue at hand: Ayn Rand’s favorite architect was Frank Lloyd Wright (the real life Howard Roark). He believed in something he called “organic architecture” which supposedly harmonized with humanity and its environment. A quick glance at Wright’s buildings shows that nothing could be further from the truth. The houses he designed more often consist of straight, brutal lines that look like they are knife stabbing their surroundings.

Its lines were hard and simple, revealing, emphasizing the harmony of the steel skeleton within, as a body reveals the perfection of its bones. It had no other ornament to offer. It displayed nothing but the precision of its sharp angles, the modeling of its planes, the long streaks of its windows like streams of ice running down from the roof to the pavements. The Fountainhead (1943), Ayn Rand

Nature is circular

Callicrates and Ictinos’ Parthenon, as a counter example, has not a single, perfectly straight line and neither does nature. Instead of trying to overcome nature, as modernists do, one should follow nature and become its master.

The city developers of the Renaissance knew this all too well. In the mid 1400s, Pope Pius II turned his birth city Corsignano into the ideal Renaissance town, Pienza. What is so astounding about Pienza is that the streets and buildings were curved and bent purposefully to make a greater impression of movement and grandiosity.

The curves of Pienza’s streets. Photo: Jaromatik

Modern human beings might ridicule these crooked old villages, yet they swarm to them. They feel at home among curves and bevels because nature is circular, not linear. There are certain proportions in regards to scale and order as well as mathematical procedures that appeal more to man’s conception of reality than others. This would be the basis for the objective position on architecture.

Now, consider the following quote from The Fountainhead:

A building creates its own beauty, and its ornament is derived from the rules of its theme and its structure,” Cameron had said. “A building needs no beauty, no ornament and no theme,” said the new architects. It was safe to say it. Cameron and a few men had broken the path and paved it with their lives. Other men, of whom there were greater numbers, the men who had been safe in copying the Parthenon, saw the danger and found a way to security: to walk Cameron’s path and make it lead them to a new Parthenon, an easier Parthenon in the shape of a packing crate of glass and concrete. The Fountainhead (1943), Ayn Rand

The notion that a building creates its own beauty is subjective and mystical. Although nature is in constant flux, this world is constructed on invariable principles. Harmony within architecture is not arbitrary and it is certainly not something that relies on a building’s personal expression.

Rand would never say about a Hellenistic sculpture that it creates its own beauty or that a work of literature is in no need of a theme. She makes a bizarre exception for architecture to be smudged with the clichès of modernism.

Did Ayn Rand break her own rule?

Her view of architecture is so out of touch with the fundamental principles of her philosophy, that one has to assume that something went wrong somewhere in her early life.

The Canadian philosopher Stefan Molyneux often ties the thoughts of great minds to their childhood experiences. His presentation on Ayn Rand’s life and philosophy of Objectivism highlights an interesting example: in 1917, following the confiscation of his pharmacy, Rand’s father went on strike and refused to work for the communists. He fought a hopeless cause, but the teenaged Rand admired him so for his steadfastness. Decades later she wrote a book with the working title “The Strike” which would come to be the most widely read book in America after The Bible. The long-length novel was published in 1959 under the title Atlas Shrugged.

“So much of what we do in life has a lot to do with attempting to save parents’ agony in the past”, says Stefan Molyneux, emphasizing that we want to re-write our parents history so that they end up as winners.

This would explain Rand’s disdain for collectivism, but what about her disdain for classical architecture?

When the young jewish girl Alisa Rosenbaum (Ayn Rand) moved to America in 1926, she left behind an anti-semitic, communist Russia that had put her family in a devastating situation. Russia and Europe were certainly broken civilizations, but they also represented a long tradition of richly ornamented, classical buildings dating back to antiquity. Alisa herself grew up in the beautiful city St. Petersburg.

On the boat to the promised land, young Alisa must have stood in awe as she reached the New York City harbor. The home of the brave, the land of the free, the cities of skyscrapers. In her own words she “cried in splendor”, amazed by the skyline of Manhattan.

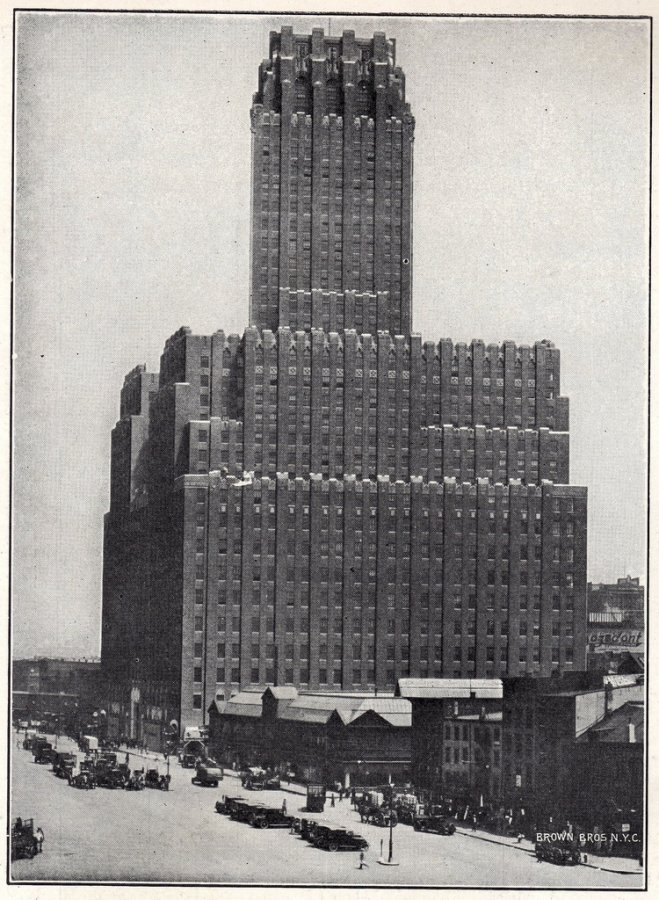

At the time, architects were still building skyscrapers in a classical manner. But the times of impressive, over-dimensioned churches, such as the Woolworth Building (1913), was over. Interestingly, 1926 was the year when the first Art Deco buildings were introduced in NYC, such as The Paramount Building.

Aerial photo of Lower Manhattan, New York City, 14th May 1926. The Woolworth building is the tallest building on the left.Source: Reddit

Voorhees, Gmelin and Walker, 1926. One of the first buildings in NYC in the style of Art Deco. Source: Favrify.com

“Form follows function” declared the creator of the modern skyscraper, the American architect Louis Sullivan (the real life Henry Cameron), who died two years short of Rand’s arrival. Sullivan’s most prominent student was Frank Lloyd Wright.

I think it is a strong case to be made that Rand broke one of her most important rules, namely that she connected her view of architecture, not to her reason, but to her emotions — specifically her emotions about escaping the Soviet Union and being liberated by the New World and all its functionality.

There is a passage in Atlas Shrugged where the heroine Dagny Taggart and Henry Rearden are driving on an empty highway in Wisconsin. She tells him that the people she hates the most are those who complain about road signs ruining the appearance of the countryside. What she seems to forget, however, is that they do not disapprove of road signs as such — they disapprove of road signs that do not harmonize with their surroundings.

If man cannot create harmonious cities and roads — is he than living or is he just surviving?

Ornaments are not meaningless, useless details, as Ayn Rand claimed. Ornament represents the abundance of human productivity. It connects man to nature and gives life higher value.

To unveil the transitory layers of one’s time is far from easy and even great philosophers are not flawless, although they come close. The rise of functionalism went hand in hand with the salvaged, americanized Ayn Rand.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with her view of architecture, one ought to recognize that there are practical defects in Rand’s aesthetic philosophy. You cannot place the Laocoön sculpture group, in all its baroqueness, in a house designed by Howard Roark. It is a conflict of interest. It does not work.

The future for architecture

Considering that this century hungers for harmonious city-planning more than any other time in history, I shudder to think of all the objectivists out there that have blindly followed Ayn Rand’s architectural vision.

On a positive note, there are tendencies in places such as England and Eastern European countries towards reviving classical architecture. But the movement lacks an intellectual backbone to gain momentum.

The controversial building project in Macedonia’s main capital is a good example. Almost ten years ago, the Macedonian government decided to renovate an entire district in Skopje with Greco-Roman-inspired buildings and monuments in honor of Alexander The Great and other historic figures. The project received fierce criticism and was dismissed as “nationalistic”, “faux-baroque”, “megalomaniac” and “historicist kitsch” (quite right). It has become an “architectural headache” for the modernists and the current government wants to and has already ordered monuments to be removed, claiming that they were “unlawfully built”.

One man can change quite a bit in this world, but if he does not change the minds of those that come after him, he changes nothing in actuality.

This is the very conclusion in Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead and she is right. People will not all of the sudden realize that they have created a society full of rubbish. One needs to entertain the minds of the young.

Published on Monday, June 24th, 2019

I stop reading with “Ayn Rand is perhaps the greatest philosopher since Aristotle”, God! Rand was only a jerk that wrote long horrible books

I think you’re wrong. I think modern architecture simply achieves harmony with nature in a different way, one that I might add is more honest. There are many instances of this but I will provide 2 of what I think are most significant. For one, the natural motifs depicted in Art Deco windows before (the international style, for instance) were only removed to make way for larger, more transparent windows that could frame the real thing, rather than a depiction. Likewise, both the reflectivity and translucency of glass can be used to the same effect. I witnessed the latter first hand on a visit to Mies’ workshop building next to Crown Hall, where a passing elevated train‘s shadow roared spectacularly across the 20 ft frosted glass wall and brought the whole space to life.

Second, Wright proved to me on that same trip to Chicago the unmistakable impact of line and geometry on our perception of space. While I was well aware of the original efforts of pioneering skyscraper architects to over emphasize horizontality in an effort to reduce the apparent height of a building, it was never so apparent as it was at the Robie house, whose monumentality struck you like a brick upon entering the courtyard, because it’s exaggeration of the horizontal made its true height incomprehensible from a mere 10 meters away. In the same way that you referred to as “stabbing”, falling water similarly uses line and geometry to extend the limits of buildings whose lines traditionally pointed upward (Away from nature) to extend outward into nature. To envelope nature, to literally pull it into the domain of the built as he does by extending falling water over the river. Material palette constitutes yet another example but no need to get into that.