News and Articles › Cave of Apelles

If the embodiment of the fundamental idea of our age were to be found in Victorian architecture […] then our age would undoubtedly be called the ‘age of kitsch.’

— Hermann Broch, author

Top list

View the entire list

What happens when galleries close down one after another and aniconism becomes the new status quo in Western countries? Kitsch painter and musician Boris Koller joins the Cave of Apelles for a second conversation with Jan-Ove Tuv.

Did you watch it? Boris Koller on Kitsch, the Art Police, and Art as the New Religion

Would you like to get premium access?

Become a patron

The Vatican’s Role in the Development of Art

Koller presents his view of the development of Art with a capital A, meaning the concept that was invented in the West in the eighteenth century. According to Koller, not only the philosophers Immanuel Kant and G.F.W. Hegel have been crucial for the modernist conception of Art, but also the Vatican and the French Revolution.

– With the Vatican in the 1700s, you have one of the strongest structures behind the term, says Koller.

Boris Koller points to J.J. Winckelmann who established the modern concept of Art while working for the Vatican. Illustration: Portrait of Winckelmann (1764) by Angelica Kauffmann.

The term Art was a new concept developed in the Vatican, to be used against the Jesuits, according to Koller. In particular, he points to J.J. Winckelmann who worked as a prefect of antiquities and scriptor for the Vatican at the time when he published his famous work, The History of Ancient Art (1764).

– Was Art an attempt to go back to the classical values?, asks Tuv.

– Certainly it was. In documents and the Pope’s opinion, answers Koller.

– So was it later perverted and turned into what we know it as today?, Tuv follows up.

Koller plays the devil’s advocate: – What do you want to call perverted?, he asks.

Tuv explains how the term originally meant knowledge, while the term Art today means non-knowledge. He calls this a perversion, or at least an inversion.

The French Revolution’s Role in the Development of Art

What would have happened if the original vision of Winckelmann had persevered and the ideas of Kant and Hegel had gone unnoticed? Would the situation for classical figurative painting have been much different?

Koller points to another aspect of the development of Art:

– You had Winckelmann, and then you have the French Revolution, he says, explaining how French noblemen travelled to the U.S. and tried out how a revolution could be organized. Then they returned to France.

– They tried to get it right, but then you have a problem with the things that remain: people and artifacts. What are you doing with these people and artifacts and paintings that represent these artifacts?

While orders were sent out to destroy everything that represented the old regime, the revolutionaries realized that there was a problem: They had to rescue something.

– They found a tool for this form of iconoclasm: The museum.

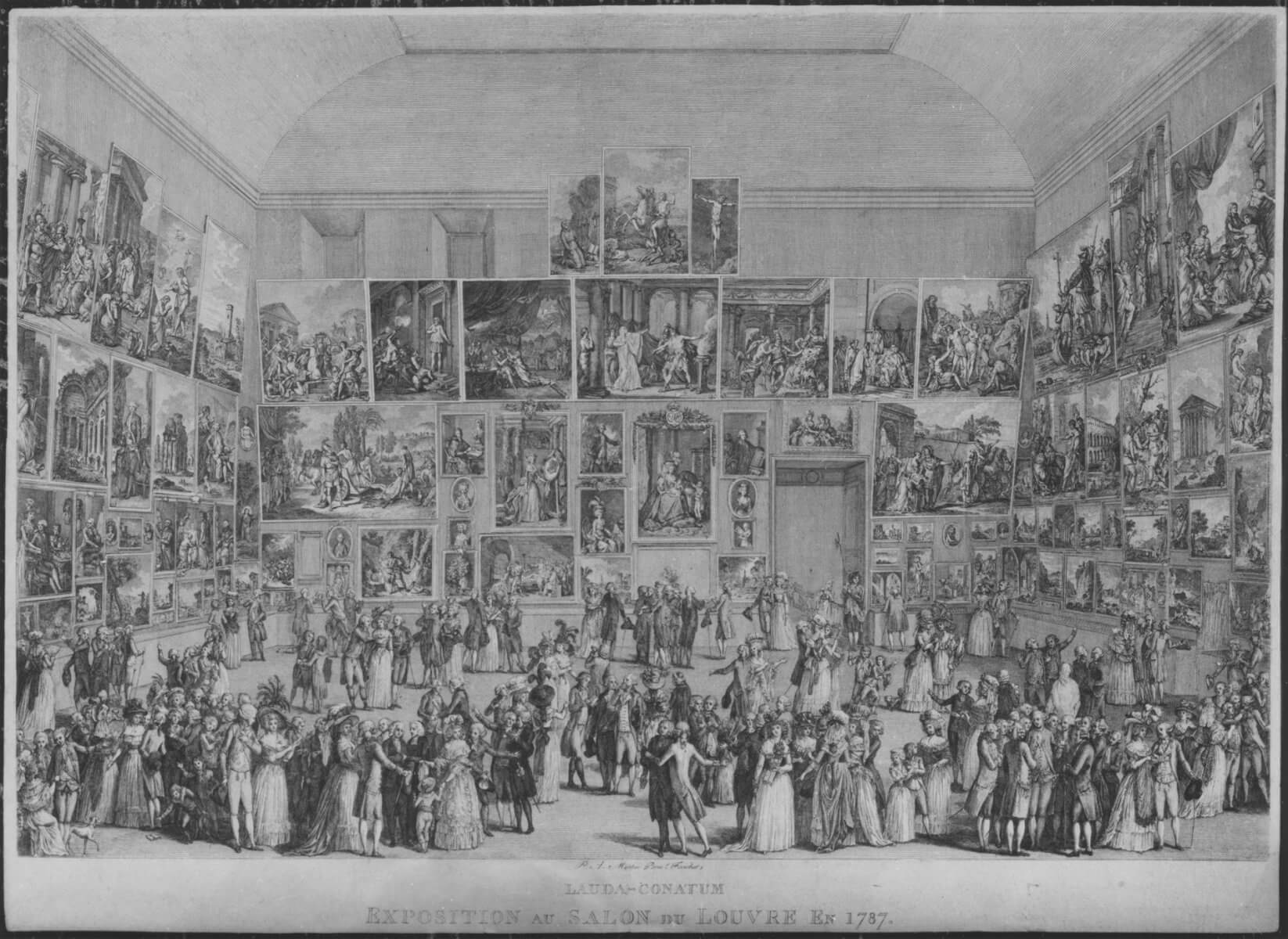

– The museums are not only protecting the old artifacts, they are also protecting you from painting new stuff, says Boris Koller. Illustration: The Grand Gallery of the Louvre, painted by Hubert Robert.

The Museum: Iconoclasm Without Destruction

Pointing to the article “Iconoclasm during the French Revolution,” Koller explains how museums constitute a way of achieving iconoclasm without destruction.

Tuv brings forth the argument of his former guest on the show, the art sociologist Dag Solhjell, who talked about how the museums saved artifacts from being destroyed. Koller does not buy this argument wholeheartedly.

– What is the use of museums today?, he asks, rhetorically. – It is a safe space for old artifacts and tourists. People from the wrong place and artifacts from the wrong time.

– The museums teach you what not to do, Tuv adds.

– The museums are not only protecting the old artifacts, they are also protecting you from painting new stuff. This has a double meaning. This is why I have always advocated for closing all the museums from public view. You should conserve the old artifacts and the old paintings, but common people should not have — as in the old times — access to it. Not even in print, Koller argues.

He explains his view further:

– Then people are demanding something. When they want to have it and when they want to pay for it — and it has to be new.

Aniconism: The Athena-Allāt from the temple of Al-Lat in Palmyra, Syria, was first decapitated by the ancient christians and then further destroyed by ISIS in the 21st century.

Aniconism

Jan-Ove Tuv points to another challenge: the similarities between the principle of aniconism in Islam and the value system of Art, such as the lack of sensuality and figurative representation. – It’s not really a culture crash at all, he says.

Koller calls this the symbiosis between certain developed kinds of religions.

– Art is a religion, and the Muslim belief is a religion. They absolutely work together. And in Europe, Christendom is no longer relevant.

– Is the problem monotheism, or is Christianity a solution?, asks Tuv.

Koller argues that religion is not necessarily a problem, but it might end up taking too much space in people’s lives. He illustrates this by pointing to religious illustrations in the old Egyptian dynasties. In the beginning there were depictions of a large prince (monarch) and a little falcon (god).

– Then, the falcon over time became bigger and bigger. And in the last dynasties it was the falcon with a little prince. It was the same development with religions in Europe. [In the beginning] it was reality with a little bit of symbolism. In the 1800s it became an obsession for religion — with a little bit of realism, Koller says and continues:

– I’m not advocating against it, but you have to do your work, that’s the most important thing, and then you can have your religion too.

Boris Koller says that the gallery system killed off the salon and created a worse situation for painters. Illustration: The salon in Louvre, 1787.

Which System Is Better for Painting?

Is the gallery system an outmoded mechanism for painters to present their works to collectors and the public? asks Tuv, reading out a question from the audience.

– Indeed it is outdated as a system, Koller says, before stating how the gallery system killed off the salon.

Tuv points to the centerpiece, Vermeer’s The Allegory of Painting, and asks: Opposed to the gallery system, opposed to the salon, the situation Vermeer was in, how was that different in terms of selling?

– When people think of Leonardo as an artist, I would like to see him in the art system today as a classical figurative painter, coming with his Mona Lisa, says Koller and continues:

– After contacting thirty or forty galleries, one accepts it. But they would have asked him “Can you make twenty of these, and make them cheaper?” Leonardo could not have survived as an artist.

According to Koller, the system of commissions is a better option. At least one does not have to “pay for the prosecco” at the galleries.

State Propaganda

On a final note, Koller points out how the state can influence good and bad taste in aesthetics. He mentions the example of emperor Wilhelm II’s installation of a new group of sculptures in Berlin — a state investment in neo-renaissance style.

– It didn’t stand that long because some decades later the war came and then in the 1950s a local conservator decided to bury the sculptures in order to protect them. They were not dug up until 1970s and have not been restored, says Koller and concludes:

– It is an example of something that was good taste, which now is considered bad taste.

According to Koller, the main problem is what to do with the old paintings — the old masterpieces — especially as the demographics change and old families no longer protect their treasures.

– I do not see that the structure will come to protect the older paintings for all time. Figurative paintings from 1890 to the 1950-60s will come onto the market unprotected. This is cultural heritage. There are no families there any longer to protect them. […] New populations in Europe are not interested in protecting the old stuff in the long run.

Koller asks the questions: So what are we doing now? What could we do to build another structure?

He has a rather grim outlook on the future of classical figurative painting. As he sees it, there are no real solutions. The only thing one can do is to prepare for survival.

This article was first published at the Herland Report.

Published on Saturday, April 25th, 2020