News and Articles › Cave of Apelles

The essence of kitsch is the confusion of ethical and esthetic categories; kitsch wants to produce not the “good” but the “beautiful.”

— Hermann Broch, author

Top list

View the entire list

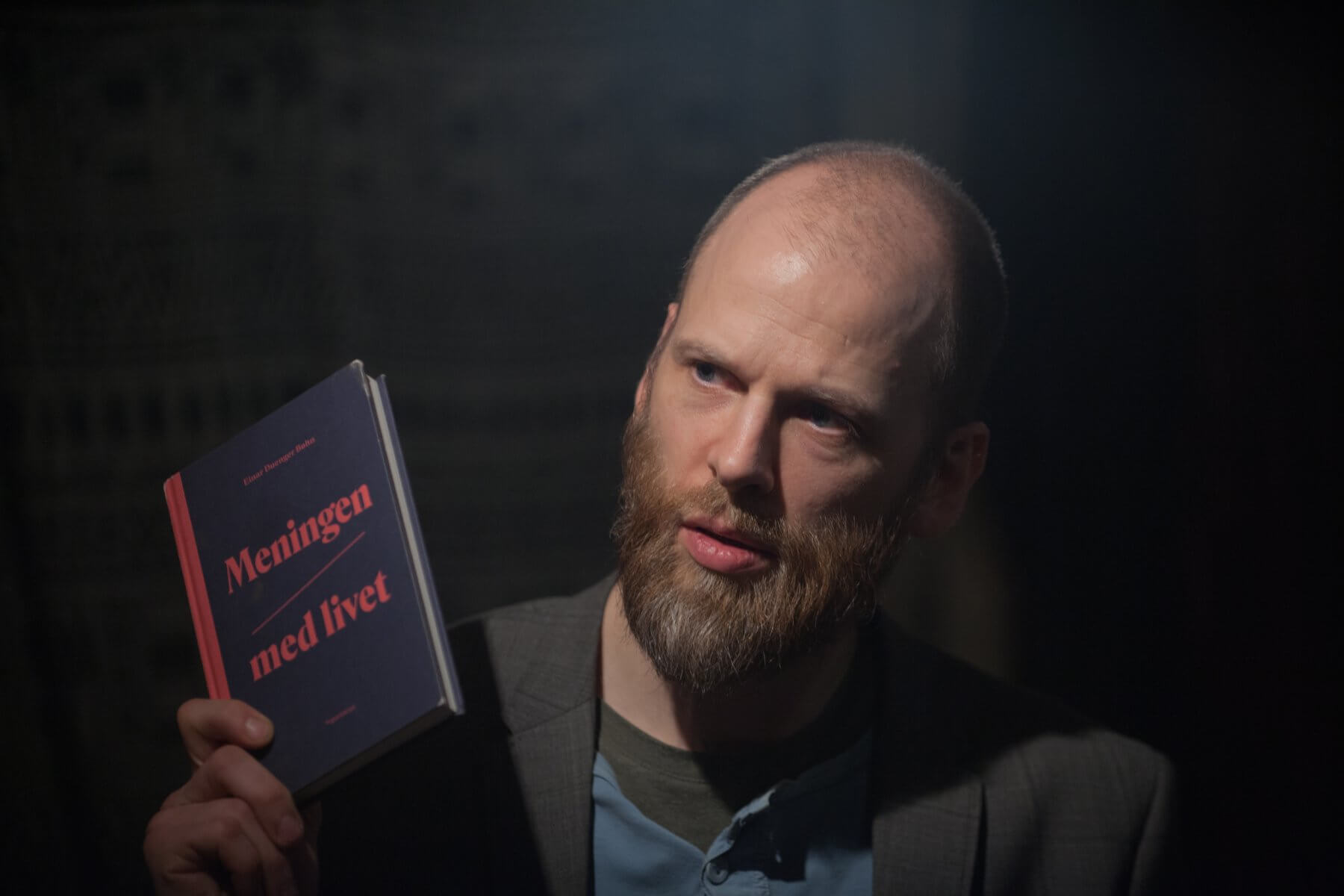

Norwegian philosopher Einar Duenger Bøhn is searching for the meaning of life. He argues that only the potential of improvement can give your life meaning.

Bøhn joins this month’s Cave of Apelles to discuss some of the topics related to his newest book The Meaning of Life, such as the existence of objective values and criteria, Aristotle’s techne, and how one with modernism loses some of the greatness of humankind.

Would you like to get premium access?

Become a patron

Sisyphus

There was a reason why Bøhn originally wanted Titian’s Sisyphus on the cover of his book The Meaning of Life. The tale of Sisyphus is a story of one who loved life on earth so much that he tricked the gods several times in order to stay on earth longer. At last, the gods lost their patience and punished him to roll a large rock up a hill, only to witness it rolling back down again. And he has to do this for eternity.

– The reason we are interested in this myth is that it is a picture of a meaningless existence, or a meaningless labor, explains Bøhn

The question philosophers have asked is: “How much does Sisyphus’ work look like our life?”

Comparing a human life to Sisyphus’ work, Bøhn finds it natural to ask a follow-up question: “What do we have to add to this existence in order to make it meaningful?”

In other words: If life is meaningless, how can we make it meaningful?

Titian’s depiction of Sisyphus, one of the four sinners of Hades in Greek mythology.

The Meaning of Life – What does it Mean?

Bøhn begins with clarifying what questions he is actually asking when searching for the meaning of life.

He says that he does not ask about the cause of our existence. The question of why we are here, is a different question.

Also, he does not ask “What is the intention behind our existence?” This too is a different question.

What he does ask is “Why should I continue living?” Or, in other words, he wants to know what the point of going on with life is. Bøhn does not think that happiness or morality are reasons to go on with one’s life, nor that they are the sources of meaning. He uses the story of Vincent van Gogh to illustrate his point. Van Gogh was neither very moral nor very happy, what drove him to wake up in the morning was his obsession with improving his paintings.

– What this illustrates is that you can be really unhappy, and you can be immoral, but the reason or the point for you to keep doing what you’re doing could be that it is very meaningful, says Bøhn.

Watch the bonus material with Einar Duenger Bøhn

Priest Shunjō Chōgen (Buddhist monk), 12th century AD by an unknown Japanese sculptor

The Potential for Improvement

The point of going on with life is the potential for improvement, according to Bøhn. Going back to the myth of Sisyphus: The reason we find it pointless is that there is no potential for improvement. The rock has to be rolled up for all eternity, with no room for improvement.

Jan-Ove Tuv brings conflict of values into the discussion, using the example of a kitsch painter who does what he considers meaningful, but meets obstacles all the way.

Bøhn acknowledges the conflict of values, and generalizes Tuv’s example: An activity is meaningful, but does not give you money. There are many values that may conflict, such as monetary needs, tradition, happiness, and morality. However, Bøhn emphasizes the importance of realizing meaningfulness as an objective, and thus fullworthy, justification:

– I think it is really healthy for your psychology to realize this: That there are actual justifications for doing this. It is not just an illusion, he says and elaborates:

– There are actual justifications for pursuing a meaningful project. I think we should recognize that. I think it is a shame when people don’t recognize the actual objective justification that lies in meaning for pursuing something. I think it hinders our cultural development, to be honest.

A bronze figure from the period of the Euroba people in 14th century Nigeria.

Subjectivity versus Objectivity

Some may say: “Well, what’s meaningful to you can be different from what I find meaningful”.

– Subjective experiences of meaning, differ from person to person. That’s not my interest. Take that with your shrink, says Bøhn, laughing.

His interest is what the actual meaning of going on with life is — the objectivity of meaning. Not only what we experience as meaningful. He explains the inconsistency of subjective experiences by mentioning that he had some experiences when he was a teenager, which he now thinks are wrong.

– Meaning is much like true love. Not just the kind of passionate desire for someone that you have in the beginning, but true love that you have for your family or for your children. What that involves is that it is a relation I have towards another person. I have love for my son, for example, and that involves that I sometimes go out of my way to make sure my son is better off, Bøhn says.

According to Bøhn, a crucial aspect of meaning is to feel that one is part of a project that is bigger than oneself. For example pursuing the skill of painting, and having one’s attention directed towards making the painting better.

– That’s a true dimension of meaning, I think. There’s actual potential for improvement, and you’re pursuing it, and it’s not about you, but it’s about the thing you’re actually pursuing, he says.

Japanese sculpture (12th century), “Sisyphus” by Titian (16th century) and a Nigerian Ife figure (14th century) on the shelf for the 17th episode of The Cave of Apelles.

Techne

Techne is a term discussed thoroughly by Aristotle. According to Bøhn, techne is an intellectual virtue that has great potential for being meaningful.

– Aristotle defines [techne] as an intellectual virtue, actually. It is a kind of skill that you have. It is a skill to produce something. Not only to produce it, but also to produce it with what he calls a true concept.

There are two degrees of techne, Bøhn explains.

The first degree is when a person who knows how to make a house, for instance. But he doesn’t really know the principles or the reason why he does everything he does. It is much like a carpenter who does what he has learned, but he doesn’t really know why he’s doing what he’s doing. This person has techne to some degree.

But there’s also a higher degree, according to Aristotle, where you know how to build a house well, for example, but you also know why you put everything where you put it when you do it. In other words, you know the principles behind why you are doing it.

– I think that’s what is meant by having a true concept of, or the knowledge of, what you’re doing, says Bøhn.

Einar Duenger Bøhn is a professor of philosophy at the University of Oslo who argues that the potential for improvement — through objective values — can give life meaning.

Instrumental Objectivity

Tuv points to the pictures on the shelf of a Nigerian figure from the 14th century, a Japanese sculpture from the 12th century, and Titian’s painting of Sisyphus, as well as the centerpiece, a portrait by Odd Nerdrum.

– These are from completely different times, from different cultures, but they base themselves on certain objective criteria. Proportions, for instance. Most cultures have been doing this, says Tuv.

Tuv mentions the example of the Chinese painter Li Cheng who used many of the same techniques to create form and depth as the Norwegian painter Lars Hertervig who lived almost a thousand years later on the other side of the globe.

– Instrumental objectivity, I would call it, says Bøhn.

Tuv brings forth the objectivity of the motif, namely the basic psychological need for archetypal imagery. He challenges Bøhn’s thesis of meaning being found in the potential for improvement: The painters who portray archetypal imagery do not attempt to improve the human condition.

Bøhn clarifies: It is not about improving the human condition per se. It is about the potential for improving the way you do something, such as improving the way one portrays archetypal images.

Jan-Ove Tuv invited Einar Bøhn to talk about his book “The Meaning of Life” in the 17th episode of the Cave of Apelles.

“I Rather Want to be an Unhappy Human than a Happy Pig”

Tuv continues by asking some questions to Bøhn from the audience.

Is it so that we can possess knowledge without having learned it from some talent or genius?

– Yes. If it’s knowledge in the sense of techne. I don’t think genius has anything to do with it. I think it has much to do with practice and hard work, and knowing what to achieve, and to explore ways to achieve it. But it would be good to look at people who have done it before you, answers Bøhn and continues:

– Hard work tends to be ignored when it comes to this concept of genius. I think geniuses are often people with a certain talent, who actually work insanely hard.

How does our time, the 21st century, compare to other times when it comes to individual happiness and meaningfulness?

Objectively speaking, the potential for meaning is the same across all times and cultures, Bøhn states, while acknowledging that the question also can be read as being empirical:

– There’s a difference to what extent we’re realizing that potential, to what extent we’re achieving that meaning, and living in accordance with that meaning. I think there are some aspects of like the renaissance culture that achieved and lived in accordance with meaning to a greater extent than we do today, he says before concluding:

– The realization differs across cultures. Which culture achieved it the most? I don’t think that is our culture…

Aristotle says that taking pride in one’s achievements is the crown of all virtues. Is it not so that this pride and the potential for improvement, result in happiness, and thus happiness is the meaning of life?

– I don’t think happiness is the meaning of life even if pursuing meaning results in happiness, because I think we can imagine scenarios where the two concepts come apart, and just imagining possible scenarios where they don’t coincide shows that they are separate, answers Bøhn before citing Socrates: “I rather want to be an unhappy human than a happy pig.”

Modernism – The Decay of Humankind

Tuv refers to an article Bøhn wrote, where criticism is directed towards modernism, using the example of portraiture. Although Bøhn finds it difficult to define modernism, and is sceptical towards isms in general, he wants to describe a tendency that kicked in within culture in general: The tendency of questioning the tradition of painting – the way of doing things.

When the tendency to question everything takes over, that’s when things start to happen, Bøhn explains. He means that in order to be corrected in a tradition, one needs to have reference points over time. As a painter, one can be corrected towards Rembrandt style, for instance.

– I think it is important to separate whether the painting is good from whether I like it. If the trend becomes that we all evaluate it in terms of whether we like it or not, or if it is “interesting” – these are very general terms that has nothing to do with techne – the objectivity in value judgment sort of fall apart, he states.

– When subjectivism comes in, then you have no ability to say whether something is good or bad, Tuv adds, before asking:

– You’re saying that with modernism, the improvement potential withers?

– Yes, it becomes harder to evaluate how to improve, basically.

Bøhn points to another problem with the modernist tendency:

– If you go away from the craft/techne aspect and only play with ideas, we lose something that makes humans a great thing. We are losing the ability to show that we can actually make some really impressive stuff, he says and elaborates:

– When we all want to just provoke, do creative things, have fun, be entertained, it’s sort of a decay of what we can actually do.

He points out that an analogy to the modernist tendency is being a teenager: Wanting to provoke, find oneself, being original. It’s dangerous when the teenage attitude becomes mainstream.

“Caroline” by Odd Nerdrum decorated the wall for the 17th episode of the Cave of Apelles.

Which One is Better?

– I think it is very simple; you compare two scenarios, Bøhn says giving examples of two painters:

One of them exhibits great skills in the sense of knowing how to paint what he wants to show, and he exhibits universal human values that are eternal that everyone can recognize across time and cultures.

On the other hand, you have a painter who also has skills, but is trying to improve his work according to other local interests and values. In 100 years, no one would recognize what it is about.

Bøhn concludes:

– Compare the two and ask yourself: “Which one is better?” And not just which one do I like the most, but which one is actually better, which one exhibits more of the greatness of mankind? The one with amazing skills and eternal values, or the one with creative or original skills and local values? Independently of what we prefer or like, which one is better? I think it is pretty obvious.

This article was first published at the Herland Report.

Published on Friday, March 20th, 2020