Modern art was an 18th century invention.

Dr. Larry Shiner, author of The Invention of Art, 2001

Before understanding Kitsch, one must look to its antithesis, Art, which came to life in the 18th century — just a little more than a 100 years before Kitsch.[1]

Wait a minute... the history of art is only 250 years old?

Let us back up a bit and look at the origin of “Art” as an aesthetical expression. A key moment was the year of 1746, as Charles Batteux arguably invented the modern distinction of Art and Science through the grouping of fine arts (painting, sculpture, music, gesture, dance and poetry).[2] There had been debate since the Renaissance about including painting and sculpture in the class of liberal arts, but these disciplines had remained restricted to the category of mechanical handcraft.

The freedom granted to painters and sculptors through “fine art” distinguished itself by exclusively recognizing the freedom of the artisan, which consequently lead to the divorce of craft from aesthetic expression.

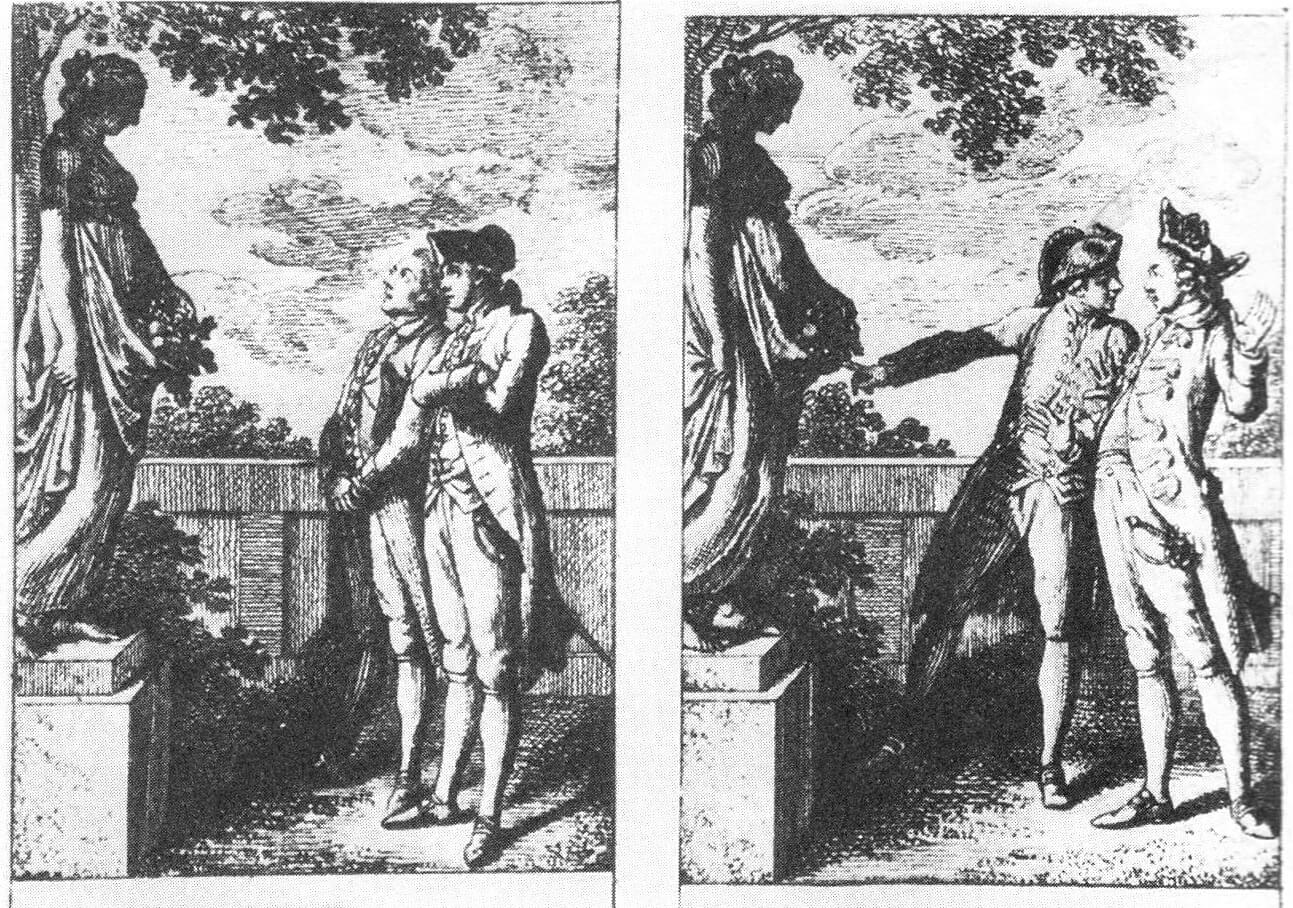

18th century Europe was subject to extensive discussions about aestehtics as examplified in this illustration of "natural" and "affected" semtiment. ILLUS. Daniel Chodowiecki (1780).

In 1790, Immanuel Kant added to Batteux's “liberalization” by providing his third critique, The Critique of Judgment. Although many of the ideas presented in this publication were fashionable in high society at the time, Kant's book would prove to be the ultimate change in course for aesthetics.

Renaissance painters had no relationship to the aesthetic terms "art" and "artist". Rembrandt, for example, was simply called a master of depiction (Schildermeister). ILLUS. Michelangelo: The Last Jugment (detail)

The Renaissance, or Antiquity for that matter, did not have expressions such as “a work of art.” Back then there was the science (ars or art) of painting, but the autonomous label of “art” did not exist, as the pre-modern understanding saw painting and sculpture as a means to an end in opposition to the concept of art as an end in itself.

But “art” is not the only term alien to painters before the Age of Enlightenment. “Artist", in its modern sense and usage, did not exist. Before the 18th century, the term was reserved for students of liberal arts, and was not a synonym for “free self-expression.”

The designation of painters and sculptors as “artisans” emerged in the 1750s, following the advancement of an exclusive group of “self-important fellows” as noted by Rousseau, which put claim to the title of “artist.”

Within short time the term widened to include composers and authors.

Art as an aesthetic expression, then, has its roots in the 18th century. Why does this matter?

Now we will throw these mediocre kitsch-mongers into slavery, and teach them to venerate the German spirit and to worship the German God.

Arnold Schönberg (denouncing the music of Bizet, Stravinsky and Ravel, in a letter to Alma Mahler, 1914)

Art is not just a new word for any kind of craftsmanship. Its philosophy is much more diverse than that, and springs out of the romantic period in Germany.

Unlike most artists and art historians of the 21st century, Schönberg and many big shots of his time were well aware of their ancestry, an awareness which probably caused Schönberg to embrace atonality in his music and proclaim exclusivity in art.

But who gave him those ideas?

Who instructed Picasso to say that it had taken him a lifetime to “paint like a child?”

And what inspired the notorious multi color palette of Cézanne or the metaphysical triumph of Duchamp?

To understand this, we need to look at the thoughts of men whose ideas have long ago been indoctrinated into everyday language in the form of meaningless clichés.

Lazarus Sichling: The portrait of G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831)

Through the ideas of these two thinkers, the painter was no longer to be an artisan, as craft was labeled “mechanic” and inferior. Further, the effect of Kant's propagation of disinterestedness had a strong effect on the Greco-Roman ideal of storytelling, which necessarily requires drama, intensity and sentimentality.

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed a gradual establishing of these ideas. Realism and naturalism emerged as the first Art styles, with their “sober” miming of everyday life.

But Kant and Hegel's philosophy would take more than a hundred years to fully realize, as they were fighting against an old world still influenced by a thinker from antiquity (see Philosophical Basis).

Let us for now take a look at the term Kitsch, how and why this word came into being and its relationship to Art.

There are different variants as to why, how and where the term “kitsch” originated, but it is said to have come into being in the 1880s, in Munich ateliers.[5]

Its function was to burn mark sentimental or dramatic storytelling, and anything considered of non-modern taste.

A brief summery of the shift from Greco-Roman to Art mentality within crafts:

The Greco-Roman values, which are also the values of Aristotle, were thus devalued by recognizing them as kitsch.

A similar method was used by the Christians almost 2000 years ago when they identified pagans with The Devil.

It was through kitsch that the modernists could belittle anything made in the classical figurative style.

At a certain point in history monuments became associated with kitsch, (it had never previously been so) and one might well ask why this unforeseen aesthetic and ethnic debasement of their values came about, or why monuments have not adapted to the times.[6]

Gillo Dorfles, art critic, painter and philosopher

The Neuschwanstein castle in Germany, also called the King of Kitsch was built over a few decades and completed in 1892. Contemporary critics saw it as nothing more than kitsch.[7]

Academic kitsch critique surfaced in the 1920s and '30s, disgracing architecture and music of unavoidable grandeur.

Witness Tchaikovsky, a “kitsch of genius,” according to Hermann Broch, or the Finnish composer, Sibelius, whose encounter with similar accusations seems to have birthed the fumbling with disharmony in his last symphonies.

Another example is the Victor Emanuel II Monument in Rome - marked by Moira Jeffrey in the Glascow Herald as “a giant piece of nineteenth century kitsch masquerading as classical architecture.”[8]

The late American painter, Andrew Wyeth, was subject to similar kitsch synonyms. His paintings have been labeled “sentimental magazine illustrations,” he has been accused of romanticizing the American rural life and for being “caught in old master trappings.”

But sociologist Elias Norbert rightly predicted in 1935 that the inevitability of kitsch could lead to its reevaluation as a positive concept.[9]

Must one become seventy years old to recognize that one's greatest strength lies in creating kitsch?

Richard Strauss, in a letter to Stefan Zweig (January 23, 1934)

In 1996, Odd Nerdrum read Hermann Broch's essay on kitsch, which describes the kitsch producer as someone solely concerned with effect, negligent of his own time and concerned with learning from past masters.[10]

To Nerdrum, the identification was immediate, as he had always identified with these values.

In 1998, at the opening of his retrospective exhibition at the Astrup Fearnley Museum in Oslo, Odd Nerdrum announced his reevaluation of kitsch as a positive concept and later wrote the book On Kitsch in cooperation with Jan-Ove Tuv and others.

Nerdrum's reevaluation of "kitsch" was discussed at the Representational Art Conference in Ventura, California 2014:

By now, you should know that the idea of Art is barely 250 years old and that its antithesis, Kitsch, represents the values that were cast out of Art.

But what exactly are the core values of kitsch?

Ref.: [1] Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art (2001) - [2] Charles Batteux, The Fine Arts Reduced to a Single Principle (1946) - [3] Immanuel Kant, The Critique of Judgment (1790) - [4] G.W. Friedrich Hegel, Introduction to Aesthetics (1835) - [5] Reimann, Hans (1936). "Das Buch vom Kitsch". Piper Verlag, München - Odd Nerdrum et al., On Kitsch (2000) - [6] Gillo Dorfles, Kitsch: The World of Bad Taste. New York: Bell Publishing Co., 1969, pp. 79-82. - [7] Wikipedia, Neuschwanstein Castle - [8] Moira Jeffrey, Herald Scotland:Belinda Guidi Project Room, Tramway, Glascow (March 2005) - [9] Elias Norbert, The kitsch style and the age of kitsch in Early Works (1935) - [10] Hermann Broch, The Evil in the Value System of Art (1933)