If you read the previous topics then you might have noticed the recurrence of one thinker.

Beside Immanuel Kant and Plato - Aristotle has had the biggest impact on painters, sculptors and writers throughout history.

The aim of the last two topics is therefore to recount aesthetic influence since antiquity and show how kitsch coincides almost flawlessly with Aristotle's philosophy.

The Renaissance was the intellectual result of Aristotle's philosophy, which in effect destroyed the Middle Ages.

- Ayn Rand, novelist and philosopher

In the 1540s Aristotle’s treatise on poetry called Poetics becomes the major topic of discussion in Venice's intellectual circles. Titian’s friend, Pietro Aretino, who up to this time had only written comic plays, would now work on his first tragedy, “Orazia”, and Lodovico Dolce came to debut in 1547 in the same mode of representation.

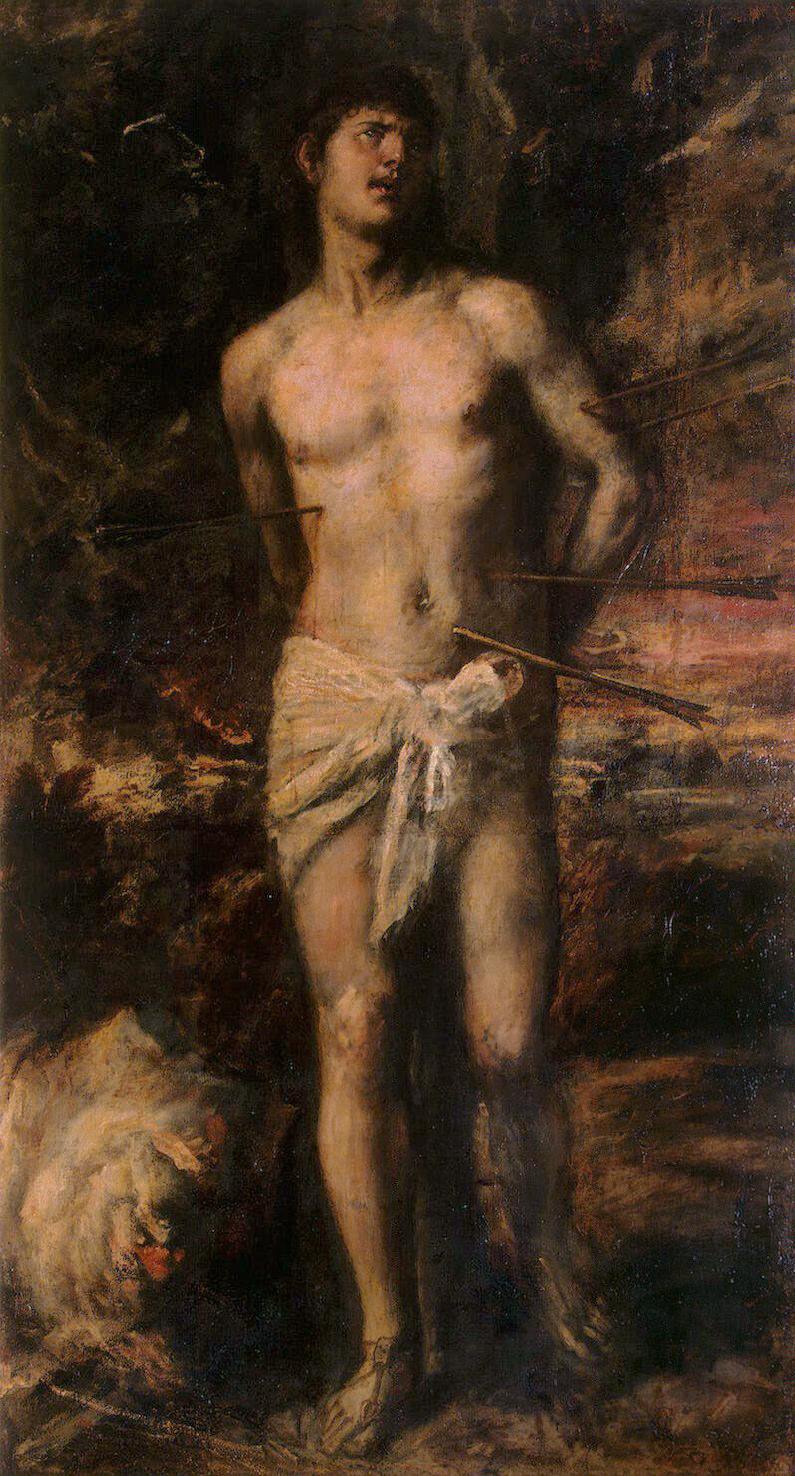

In his book Titian and Tragic Painting, Thomas Puttfarken suggests the influence of Aristotle's underworld on Titian's work. ILLUS. Titian: St. Sebastian (1570)

Titian's contemporary colleagues likewise went from referencing biblical stories to depicting mythological motifs incorporated with drama and pathos, drawing inspiration particularly from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Why?

Let us take a close look at Aristotle's ideas - not only expressed in his Poetics - but through a wide range of his surviving work.

Aristotle argued that...

Since the re-discovery of Aristotle (c. 1000 A.D.) the idea of imitation has had significant impact on the development of European culture. Study of the Ancients began with Romanesque architecture in the 11th and 12th centuries - a trend that saw its peak in the High Renaissance when architects, painters and sculptors literally aimed at re-creating the Golden Age of ancient Greece.

Ironically, this movement birthed several masters that are today praised by art historians for their "originality."

Poetry utters universal truths, history particular statements. For this reason poetry is more philosophical and more serious than history.

- Aristotle, philosopher

Brunelleschi imitated ancient building techniques to create the massive dome for the Cathedral in Florence - Michelangelo copied The Belvedere Torso (c. 1st-century BC) into several figures in "The Last Judgment" - Rembrandt used the same palette as the Hellenistic painter Apelles - and the list goes on.

Perhaps the best example of Renaissance revival is the late works by Titian.

Titian arguably reached the closest resemblance to the lost paintings from antiquity because he followed advice by Aristotle - literally - and more than anyone else.

In the mid 1550s, Titian began working on The Four Sinners for Mary of Hungary. This cycle depicts Sisyphus, Tantalus, Tityus and Ixion in the ever-repeated tortures of the underworld, and it is believed that Titian was inspired by Aristotle's four kinds of tragedy.

Later work is often dark - with theatrical figures glowing out of a murky background - as if they were "staged in the underworld" described by Aristotle.

Left: St. Margaret and the Dragon (1559) by Titian. Middle: Juan Rexach (c. 1456). Right: Benvenuto Tisi (16th century)

Another example is the story of St. Margaret of Antioch and the Dragon. The legend, told by Jacobus de Voragine, describes the Saint as fearless in her meeting with Satan (shaped as a dragon) because of her unshakeabe belif in God.

Compared to his contemporaries, Titian gives a rather realistic account of the story. In his version, the background is covered with stormy weather over a city, reflecting the deadly fear in St. Margaret's face as she makes the sign of the cross, seemingly God-forsaken and left to her own fate.

This interpretation of the Christian legend correlates with Aristotle's principle of probability and the achievement of evoking pity and fear in the audience.

Art for art's sake is far removed from Aristotle's aesthetic theory.

- Sir Anthony Kenny, translator of Aristotle's Poetics (Oxford World's Classics 2013)

A "modern" person in the High Renaissance was an "up-to-date" man who rejected Medievalism and cherished the revitalized values of Ancient Greece. The term "Modernism" from 1737 means the exact opposite — literally defined as that which deviates from "the ancient and classical manner." When Kant wrote The Critique of Judgment in 1790, the world of painting and sculpting had already changed drastically in Europe. Works made in those times consisted mostly of portrait commissions and similar assignments, but people, and especially the intellectuals, believed in the autonomy of art:

That art could be viewed without being presented in a particular way – that freedom was the formula for great art, not craft.

Kant's influence on aesthetics, however, is of no less significance.

Where an author owes a product to his genius, he does not himself know how the ideas for it have entered into his head, nor has he it in his power to invent the like at pleasure, or methodically, and communicate the same to others in such precepts as would put them in a position to produce similar products.

- Immanuel Kant, philosopher

While earlier 18th century thinkers emphasized the treatment of painters and sculptors and the utility of their work, Kant's main interest was to unveil the false and the true judgement of “beautiful things.”

His philosophy on beauty would come to be the philosophy of modernism/art and the Genius.

Immanuel Kant's first point is that the judgment of beauty is an aesthetic undertaking and not a logical one. Beauty can only be experienced and not explained, we can therefore not conclude with what is beautiful and to create beautiful things from a formula is impossible.

Since “beauty” and similar expressions must be applicable to everyone (according to Kant, the words and their meaning are otherwise without purpose), viewing the beautiful object must be a contemplating experience devoid of interest. Interest in the object would be partial, and Kant describes a pure judge as a person who in silence watches an object and has no interest in sharing this experience with others. He cannot discuss this object with his friends, since the experience of the object is subjective. Beauty is also beautiful regardless of what it represents and ought to be judged without any knowledge of what the thing is. Kant writes that a beautiful building is beautiful until you see that it is a church, and a human body can never be beautiful because of our sexual desire for it.

Kant's idea of viewing works of art devoid of interest resulted in motifs with less depictions of dramatic events and storytelling. Kant's aesthetics broke through in the early 20th century as art became autonomous in the very sense of the word. ILLUS. C. D. Friedrich: The Wanderer above the Sea of Clouds

Kant calls this “nature beauty”, which is falsely believed to be the evidence of Kant's support of art that represent nature.

“Nature” or “natural” for Kant and the majority of philosophers after him, means “by nature” or “true.” Opposite to “nature beauty” is “art beauty” which is not truly beautiful as it deceives.

True, beautiful art is like it is “of nature,” as original as “nature,” not a copy of nature.

The maker of beautiful nature art (fine-art) is and must be a genius, and without man's knowledge, the genius gives the rule to art. The genius is the maker of true beauty, sublime art. The genius inhabits man from birth, it gives him validity as a superior artist without any learning involved – the genius simply acts upon its own whim.

While Kant says that any criteria for great art would be to dismiss beauty at all, he has some preconditions for it to become beautiful art:

Considered formally, even a useless notion that enters a man’s head is higher than any product of nature.

- G. W. F. Hegel, philosopher

Being an anti-materialist, Hegel believed like Kant that something non-material always presided the world. He called it spirit.

As opposed to Kant, Hegel thought that nature beauty could never be as great as that created by man – because a man-created object has spirit. He wrote that earlier practical writings on aesthetics, like Aristotle's Poetics, were prejudicial because they referred to the ideal form. But now, as Hegel wrote, we have the Genius with the spirit, which transcends the form of the work – which can make all works of art great, regardless of its form.

Hegel actually goes so far as to suggest that a work made by spirit is more worth than any nature scenery no matter how ugly the artwork is and how beautiful the scenery is – and that an artwork actually is not the highest form of spirit there is, because it has a form.

Is this the birth of performance art?

Like Kant, he believed in an autonomy in art. Beauty, Hegel said, comes from the substance and not from what it represents (if it represents something). In art, as opposed to other things, we search for comfort and something new.

And this new is a glimpse of the truth. According to Hegel, truth is synonym with beauty, and the greatness of art during the years is that it has had the ability to show us through spirit: the truth; and it has covered the immediate sensuous, which is the opposite of what an artwork has the righteous ability to do.

Conclusion

Immanuel Kant and G.W.F. Hegel introduced the following ideas which has been maxims for artists and art-historians since the late 19th century:

One of Hegel's most influencing ideas is Zeitgeist, history of art as a continuous line of pre-determent ideas. This means that, impressionism was destined to succeed naturalism and expressionism was destined to follow after that. In this mindset, creating something so called “Old fashioned” in the 21th century is outrages, it is not right – it is not the time for that now - it is kitsch.

In terms of the values of Art, Aristotle has been criticized frequently the past century for his book on poetry. According to author Joe Sachs, translator of several writings by Aristotle, people claim the ancient Greek philosopher to be “an unpoetic soul” and that storytelling, a keypoint in the Poetics, is the least significant poetical element.

Some twenty five years ago it was rather the fashion among commentators to deplore that Aristotle should have so much inclined to admire a kind of tragedy that was not, in their opinion, "the best." All this stress laid on the plot, all this hankering after melodrama and surprise – was it not rather unbecoming – rather inartistic?

- Dorothy L. Sayers, author (5. March, 1935)