The Winner of Jury’s Choice 2018 — a Peak at the Dynamic World of Breton’s Paintings

By Bork S. Nerdrum

News and Articles › Contests Paintings and drawings

Kitsch is certainly not “bad art,” it forms its own closed system.

— Hermann Broch, author

Top list

View the entire list

Scott Breton (b. 1982) lives in Brisbane, Australia. Working in traditional drawing, painting and sculpture, he is interested in the interface of the modern human experience with the timeless human condition. Lately, he has traveled to US and Europe to study with classical painters, an experience which has enhanced his view of the relevance of Renaissance thinking in the 21st century.

In 2016, Scott cofounded TIAC (The International Arts and Culture Group). In 2018 he won the World Wide Kitsch Competition.

We seized the opportunity to interview Breton to hear his thoughts about painting and philosophy.

Long Timber by Scott Breton

The perspective in your works is distorted, bordering on improbability, and there are movements going in all directions, creating a vibrating, living image. What are your sources of inspiration?

SB: Primarily, the human body. I was 16 when I began classes with a very good draftsman drawing the model from life, and have continued cultivating this skillset for many years since. In Australia, sessions of short poses from 1 minute to 30 minutes are quite popular, and lend themselves to dynamic poses. As I have continued to practise, and look at the work of the Masters, I suppose I have evolved towards an Italian Renaissance tendency of focussing on the energy and gesture of a pose through an emphasis of rhythmic relationships, and a sense of the volume of the whole figure in space. I have a great fascination for how a static image can feel like it is moving – as though the painter is able to transmit to the viewer the sensation of the gestural and volumetric quality that is so palpable when observing the figure or landscape from life. What I mean is that when I am in a landscape, there is a sense of potential paths all around me, by which I could explore this vast sculpture: we know the landscape by walking through it, similar to how the sculptor gradually moves around the sculpture to apprehend it in the round. The paths call to you, and you have the sense of being a perceiver at a specific position, of a first person perspective.

You always seem to create a breathing space where the warm rays of the sun can shine through?

SB: Thank you, certainly I am trying to. I think that to attempt to compose with light and space rather than only area and tone is one of the things that distinguishes a classical or traditional compositional approach.

Scott Breton at work in his studio.

Inspired by Bastien-Lepage

Breton says that his prize-winning work “The Sea has many Voices” was inspired by the painting of Joan d’Arc by Jules Bastien-Lepage. The martyress of the Medieval Period became a patriotic symbol when the French ceded the territory in Lorrain to Germany after the Franco-Prussian War. Lepage, a native of Lorraine, depicted the moment when Saints Michael, Margaret, and Catherine appear to the peasant girl in her parents’ garden, rousing her to fight the English invaders in the Hundred Years War.

Unlike Lepage, however, Breton did not have a political motivation for making his painting.

SB: The pose is closely related to the pose in his picture. My picture is not specifically Joan of Arc though: we might say that the protagonist is simply at the “calling” stage of her Hero’s Journey. She is young and vulnerable but has a sense of strength. The epiphany has come, and she can not go back. She is afraid to go into the unknown but she is also excited. There is a grandness and a sadness in the humble yearning for meaning.

Going to the beach at dusk seems to tap us into questions of meaning and purpose. We look out to sea and wonder about what we should be doing, at the grand forces going on around, and within us, that we may have no control over. Or that we might.

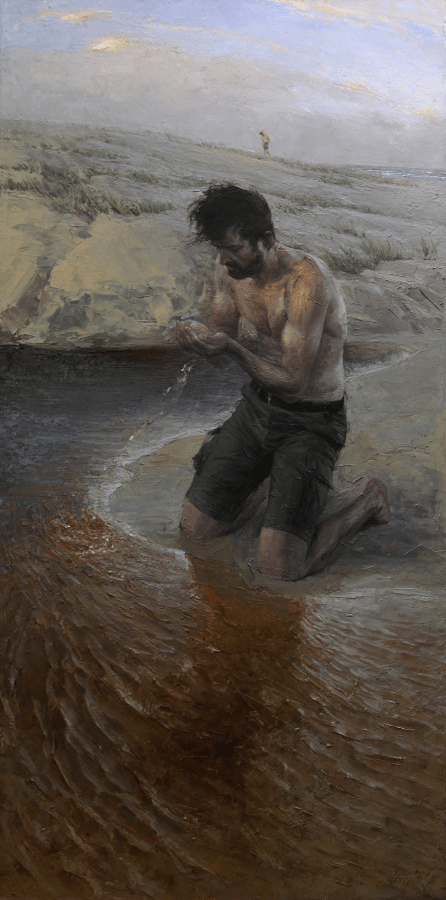

Winner of Jury’s Choice Award in the WWK Competition 2018: The Sea has many Voices by Scott Breton

Joan of d’Arc (1879) by Jules Bastien-Lepage. Gift of Erwin Davis to the Metropolitan Museum, New York in 1889.

Your recent work is rendered in a loose manner?

SB: I am interested in brushwork as part of the visual experience – not as artifice but as the natural result of efficiency in the craft. I think it implies the intentions and thought process of the painter. So, for instance, if one paints broad relationships and movements and proportions to begin, and gradually resolves into higher resolution important areas such as faces or hands, there is logic that emerges, a hierarchy of importance. I think this hierarchy can be stimulating to the eye, in the way it simplifies and amplifies but can also veil and make mysterious. Like the way a singer performs a piece, it is sometimes hard to define why one particular application of paint sparks magic. But in my experience, it is better for the painter to set the intention on the form, light, emotion, gesture etc and let the brushwork emerge out of this intention rather than seeking interesting brushwork as a contrivance.

Scott Breton at work in his studio.

What do you do to stay focused on classical painting — to not loose yourself to the many trapdoors of the modern world?

SB: When I was younger I experimented with abstract painting and so on, and I was influenced by modernist aesthetics to some extent. But I have gradually found that the work that really means something to me, that I keep going back to, is work that is primarily some form of sincere representation. It has been a case of coming home to what I always loved. I also think it is important to cultivate internal awareness to distinguish between when something is appealing in its own right, and when something has an appeal out of the desire for social acceptance, out of fashion. What do you really want to look at/ create, if you were really honest with yourself? Humans are complex animals and we delude ourselves easily. I think self knowledge via introspection is really important.

Scott Breton: “Finding Freshwater

How is the situation for classical figurative painting in Austrailia?

SB: There are some very good classical figurative painters in Australia. However, as in other countries, where representational painting is concerned, the tendency seems to be towards either undisciplined expressionist type work or carefully copied photographs. Carefully, plastically crafted images based on cultivated and fluent skill are rare.

If they are rare, how come that you are currently crafting those images yourself — did someone influence you from early on?

SB: Yes, I suspect that the inclinations that have led me to this point are partly due to being exposed to great artwork as a child, for example Rodin and Michelangelo, that my mother had books about. There were other influences – such as in Australia we have these folk poets (often called “bush” poets) from the 19th century who had this sad romance about life in the frontier areas of the past. I grew up on a cattle farm and there was always a sense of the grandeur and simplicity of nature, and something magical in riding a horse through the bush. For as long as I can remember, I have had a kind of romantic yearning for meaning, for something beautiful in human beings, and I have found cynicism distasteful. I think this sensibility exerts a kind of gravitational pull towards to wanting to shape something to contain and share these feelings, and the classical composition seems like the only form big enough. It can be scary to expose these feelings in a work, but I don’t want to pull my punches.

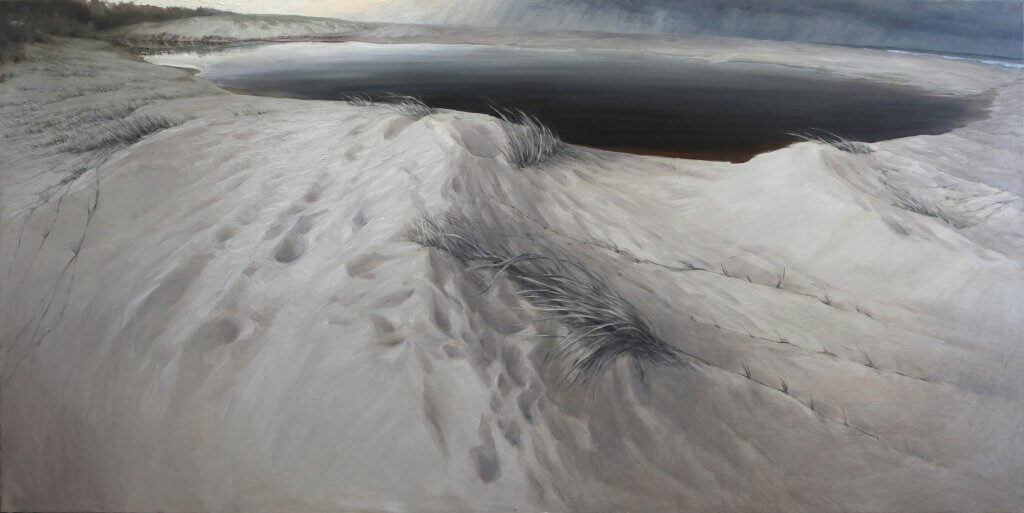

Scott Breton: “Black Water” (Tea Tree Creek, 61 x 122 cm, Oil on Linen

In a few words, what are you aiming at in your work?

SB: Excellence of craftsmanship, a spirit of vitality, and a truth of the human condition. To make the invisible internal experiences of the human being manifest and comprehensible by the audience.

Sort of like Aristotle’s statement that poetry utters universal truths, which for that reason makes it grander and more serious than a strictly historical image?

SB: Yes I think so. But I suspect that the nature of the truths being uttered are hard to define intellectually only – they involve subtle subjective states of mind, of being – and this is why we use images, why we use the expression of the human face and the gesture of the human body. These things can communicate directly between human beings. So we can talk in words about values and other ideas, and this is useful, but the representational painter or sculptor can transmit more directly what it feels like to be in a state that is living these values.

Published on Saturday, December 8th, 2018