News and Articles › Cave of Apelles

Kitsch tends to wallow in beauty – its shortcoming is not aesthetic, but ethical.

— Hermann Broch, author

Top list

View the entire list

Markus Andersson joins Jan-Ove Tuv in the May feature of The Cave of Apelles to share his bizarre story of how the media and the art establishment managed to drag his painting “Swedish Scapegoats” (Svenska Syndabockar) all the way to the Supreme Court – a story of character assassination and judicial murder.

Andersson is a Swedish figurative painter influenced by painters such as Anders Zorn, Prince Eugene, Carl Larsson, and Bruno Liljefors, all of which have nature as a central part of their paintings.

We need your support. Donations are tremendously important for the continuation of this show. Make a donation to Cave of Apelles for more quality conversations.

A Succès de Scandale

Around the year 2005, Andersson complained to a jury for an exhibition that the field of contemporary art was too narrow. One juror, The Romanian conceptual artist Dorinel Marc, agreed with him and half a year later, Andersson exhibited 22 paintings at the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm as part of Marc’s installation.

“Did you have a name at that time?” Jan-Ove Tuv asks.

Markus Andersson shakes his head.

“This exhibition at the Modern Art Museum,” Tuv continues, “what kind of status does that have?”

“They say that in this exhibition – they have it every fourth year – they invite the fifty most important contemporary artists,” Andersson says.

Markus Andersson and Dorinel Marc posing in front of Andersson’s 22 paintings that were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm, Sweden in 2006 as Marc’s installation. Photo: Anna Bergqvist

Most of his paintings were Swedish landscapes. But his exhibition wall also included works that depicted politically charged people – a series he called “Swedish Scapegoats” – which was different from what he normally painted.

At first, the figurative wall received good reception among some critics who, according to Andersson, praised Dorinel Marc for his “interesting paintings.” Andersson says that one critic even wrote that the paintings were “wonderfully braindead.”

It took one month, he says, before the press began to realize what was actually going on:

“They started to say that it was nationalistic… kitsch paintings. I even think that they claimed that it was nazi painting or something like that. They had all those buzzwords.”

The exhibition quickly evoked controversy in Sweden, especially among the media and the art establishment, as it was neither aesthetically nor politically correct. The paintings were figurative and without irony, while the people depicted were regarded as politically suspicious by the media. The reactions to Andersson’s paintings culminated in a judicial process lasting for ten years, going all the way to the Supreme court.

“The real poetry will be lost because all painters and writers will only try to do what is politically correct,” says Andersson, arguing that the judicial process and character assassinations he faced were attempts to silence him.

Jan-Ove Tuv gesturing at “Swedish Scapegoats” during his conversation with Markus Andersson. Photo: Cave of Apelles

The Scapegoats

I wanted to paint something that had been hidden from the media. The people were from quite different backgrounds. There was no connection between them, except that the media had used them as scapegoats, or that their voice had been silenced.

– Markus Andersson, Cave of Apelles 2019

One of them, which ended up being the most controversial painting, was a painting of Christer Pettersson, who was accused of murdering the Swedish Prime minister Olof Palme in 1986. He was sentenced to lifetime imprisonment, but was later acquitted and released.

The media, however, continued to claim that he probably was the murderer.

Markus Andersson’s painting “Swedish Scapegoats” (Svenska Syndabockar), 2005Photo: Anna Bergqvist

Christer Pettersson was from the lowest of the lowest part of the society. I think the reason why they took him was that he was an easy target, and because he has an archetypical look.

– Markus Andersson, Cave of Apelles 2019

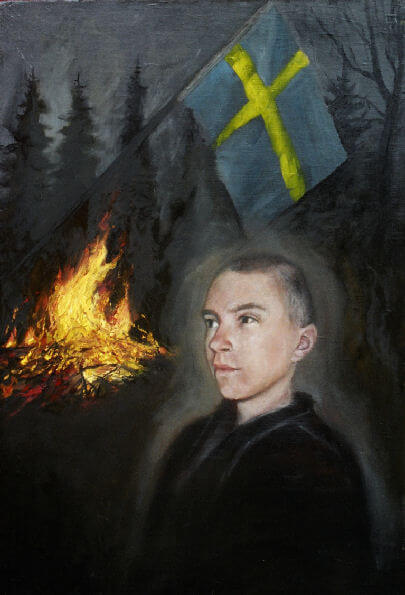

Markus Andersson’s portrait of Daniel Wretström, also known as “De Förlorade Drömmarnas Skog”, Oil on canvas, 70 x 95 cm, 2005 Photo: Anna Bergqvist

Another “scapegoat” portrayed by Andersson was the 17 year old Swedish boy Daniel Wretström, who was lynched and killed by a group of around twenty by-passers. The media claimed that the reason why the boy was assassinated was that he was a right-wing extremist.

“It is absurd to discuss what opinions that boy might have had,” Marcus Andersson says, “he was murdered and lynched on the street in a horrible way. And what he thought and his private opinions should not matter. It is as ridiculous as if a woman gets raped, one starts discussing that her skirt was too short.”

Making the Scapegoat series was about the principles. Although one strongly disagrees with someone’s opinion, they should be safe from being lynched and killed in the streets.

– Markus Andersson, Cave of Apelles 2019

There’s something rotten in the state of Sweden

The first reactions to the exhibition were epithets from the media and art critics. Not only did they react to the scapegoat paintings, they also reacted to a classical painting of a nude blonde woman in a Swedish landscape. One critic said that when painting a blonde nude, one “idealizes the Nordic”, the implicit message supposedly being that “something else is dirty, ugly and weak”. His painting of a boy by a rune stone was also attacked for having Nazi connotations.

They had different kinds of ammunition against me. They started with the political, claiming that I am a right-wing extremist, or something like that. Then, they reported me to the police for copyright infringement.

– Markus Andersson, Cave of Apelles 2019

Still photo of Markus Andersson. Photo: Cave of Apelles

For one of his “scapegoats”, his portrait of Christer Pettersson, Markus Andersson had painted after media pictures. One particular was taken by the photographer Jonas Lemberg, who belonged to an influential media family in Sweden. Lemberg reported Andersson to the police for copyright infringement.

The photographer, who accused Andersson of copyright infringement, posing in front of the painting “Swedish Scapegoats.”

The police, however, did not take the case, as it obviously is no crime to paint from a photograph. “Then, they found a prosecutor, who did an investigation for eight months. But she also concluded that there had been no crime, no copyright infringement. At that time, I thought it was all over,” says Andersson. He could not have been more wrong.

One day, one of the largest newspapers in Sweden, Expressen, publishes an article about him, best described as one large and nasty character assassination. The following day, the head prosecutor in south of Sweden, argues that it is necessary to start a new investigation of Andersson’s painting. “The police have to do their homework,” the prosecutor argued.

Andersson ended up being interrogated at the police station.

It was absurd. My lawyer told me that I did not need to lie, because I had done nothing wrong. I told them that I found pictures in the newspaper and used them to paint from. The interrogation lasted for one and a half hour. Can you imagine? And this was at the police station, where they interrogate bank robbers, murderers… and painters!

– Markus Andersson, Cave of Apelles 2019

In 2008, he was informed by mail that his case was obsolete. “So, they did not acquit you explicitly? They just concluded ‘we cannot touch him?’” asks Jan-Ove Tuv.

“Correct, and again I thought I was done with the case. But in 2013, five years later, I received a new letter from the civil court. The photographer wanted a new process against me.”

During a period of more than two years, the case went from district court (where he lost) to the court of appeals (where he won). But the photographer appealed again and one year later, the Supreme court accepted the case. “They accept very few cases,” says Andersson, and continues:

“If there is a question whether this is copyright infringement, then the majority of the modern art scene is copyright infringement. So why did they pick me, then?”

“This must be absurd for you,” says Jan-Ove Tuv, and elaborates: “You make this painting series about character assassination and hypocrisy… You can include a self-portrait in the series!”

Detail from Markus Andersson’s painting “Swedish Scapegoats”. Photo: Cave of Apelles

The verdict from the Supreme court, however, was clear as day: “The statement from the Supreme court was like a legal precedent: You can use, or get inspiration, from media pictures or whatever, as long as you make something unique. It is that simple,” says Andersson.

“Students often ask me if they can paint a rabbit from a picture in a book, for example. Now I have the verdict I can show them!” he says, bursting into laughter.

– Freedom of Speech is Inconvenient

“You were stripped of all talent in the newspaper, you were accused of being politically suspicious. In short, the partisan blog mob went after you. It was not given that you would survive this,” says Jan-Ove Tuv.

“In today’s society, people accept accusations too early, without a real fight, without defending themselves as hard as they can,” says Andersson and continues:

“If they can scare people and make them fear expressing themselves, it would stop every kind of interesting creativity. For example, in a normal bookshop today, we don’t have any brave writers. Or, it looks like we do not have any, but I know that we do. Actually, I know some of these brave writers, but their books are not sold in the book shops in today’s society.”

“The same people honor Solzhenitsyn, who had to hide his manuscripts from the government. It’s a heroic act if it happens there, but not if it happens here,” says Jan-Ove Tuv.

Still photo of Jan-Ove Tuv. Photo: Cave of Apelles

We need freedom of speech to be able to breath in an intellectual way, and almost in a physical way as well. […] If we don’t have freedom of speech, we cannot create any culture at all. Everything will be only propaganda. There will be no independent creators.

– Markus Andersson, Cave of Apelles 2019

“The situation where one doesn’t understand the proportion of crimes, knowing what is actually serious and not, is a problem,” says Tuv, as he emphasizes the absurdness of Andersson’s painting ending up in the Supreme court.

“There are many people who don’t like freedom of speech, because it is somewhat inconvenient for them. Freedom of speech is inconvenient,” says Andersson.

“Has this ever scared you, or prevented you for doing something in fear of reprisals?” asks Jan-Ove Tuv.

“I’ve not been scared personally. But I’m scared of this dark movement where freedom of speech is not that important anymore. I’m scared in general for the future, for society,” Andersson concludes.

This article was first published at the Herland Report.

Published on Monday, May 13th, 2019