News and Articles › Cave of Apelles

Music draws tears more quickly than a painting. Tears must be held back. The eyes are needed to see.

— Odd Nerdrum, kitsch painter

Top list

View the entire list

In this month’s episode of The Cave of Apelles, host Jan-Ove Tuv has invited kitsch painter and member of the Memorosa Group, Nic Thurman, to the show. As a matter of fact, Thurman is the fourth member of the Memorosa Group to guest the show — in addition to Öde Nerdrum, Sebastian Salvo, and William Heimdal – yet the first one to explain more in detail what the group actually amounts to — such as the practices they exercise and the dogmas they follow.

Would you like to be credited as a supporter in future videos?

Become a patron

The Memorosa Group

Nic Thurman mentions that the Memorosa Group arranges “drowning competitions,” otherwise known as drawing competitions, on a daily basis.

– Drawing is an excellent way to learn things that are useful in painting. And the point of having a competition is that it really gets you in the mood to make a drawing, he explains.

The competitions last for 60 minutes. Nothing more, nothing less.

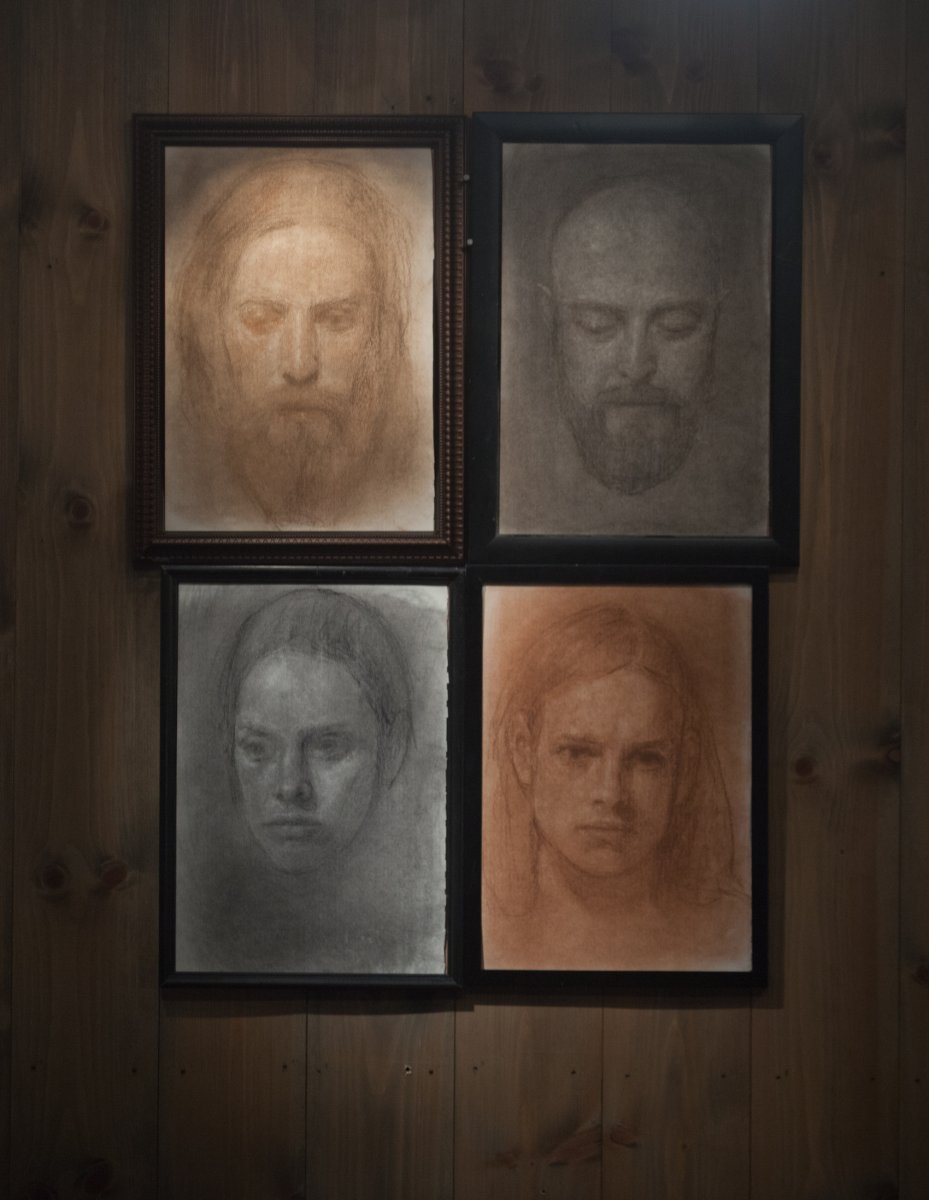

The Memorosa Group: Javier Adams, Sebastian Salvo and Nic Thurman competing to make the best one-hour drawing. Photo: still image from the documentary “The Memorosa Group”.

– It is mostly spurred by Odd Nerdrum. When he has students in his studio, he wants to draw live models. but he will also invite the students to compete alongside him, Thurman says, elaborating that what the Memorosa Group did was simply to continue the same routine in Nerdrum’s absence.

– One should start with getting the form, Thurman explains.

Having outlined the whole head, and marked where all the features should go, Thurman has a structure to work on. Using a technique he learned from Odd Nerdrum, he then wipes out the face with toilet paper to soften all transitions and lines. With this technique, one gets a good baseline, from which one can continue by adding highlights and marking sharp lines.

Watch the bonus material with Nic Thurman

Avoiding the color blue

The Memorosa Group has a clear set of dogmas which came to attention and spurred debate after a video of Öde Nerdrum talking on behalf of the group and their set of rules was broadcast on national television in Norway.

– The dogmas are guidelines to how one can make the best painting, explains Thurman, before listing up some of them:

- Paint timeless and archetypal motifs

- Paint from life

- Avoid the color blue

– The ultimate goal is the eternal masterpiece, so all of the dogmas are leading towards that, he continues, calling them guiding principles.

Thurman points to Aristotle, who stated that one should make one’s own empirical observations:

ON THE WALL: Four one-hour drawings by Nic Thurman

– We encourage people to try these dogmas and see how it changes their work. We don’t say “You have to do this”, you know, be-all-end-all, but if you want to make a masterpiece, this is the guidebook on how to do it, he says.

#KITSCHIFIED

In the first days of February, the #kitschified campaign impacted some figurative painting communities, raising awareness around the personal costs of obedience to the rules of the art world. Many people shared their stories about why they stopped conforming to the values of art and refused the label “artist”.

– The goal of the #kitschified campaign is that we want to distinguish between the values of art and the values of kitsch. The way we are doing that is by showing that paintings which are made in the kitsch value system, are not art. Particularly the old masters, says Thurman.

Detail of Nic Thurman’s one-hour drawing of William Heimdal.

What Nic Thurman is referring to is how “kitsch” came into play after the coinage of the term “artwork” in the 1700s, which broke with the old master values and paved the way for the modernist tradition that is dominating in today’s culture.

Thurman points out that the individual stories in the #kitchified campaign is the personal component, whereas the main point is to emphasize the impact that philosophy has on people’s lives.

– If someone doesn’t want to call themselves a kitsch-person for some reason — good or bad — at least people should understand that Fine Art is an invention of the 18th century that broke radically with the old masters. If we can get that far, a lot has been established, says Tuv.

– That’s the goal of the kitschified campaign, Thurman replies.

You can read Nic Thurman’s own story about why he stopped calling himself an artist here.

Edvard Munch’s old master painting: “The Sick Child” (1886)

The Greek Edvard Munch

In November of 2019, Thurman visited the Munch exhibition I oss er verdener in Bergen, which happened to coincide with the opening of an exhibition by the Memorosa Group at Kunsthuset Wendelboe.

Thurman was struck by the painting Inger on the beach, and how Munch had clearly imitated the old masters in this painting.

– What are the technical similarities between Munch and for instance late Rembrandt, asks Jan-Ove Tuv.

– First of all it is the totality, that he is focused on life, concerned with the single figure, and he always puts the focus on the face, Thurman responds.

He also mentions the sense of space in the painting as another aspect that Munch has in common with the old masters, as well as the softness of the form. Munch often used the canvas as an integral part of the painting, letting it blend things together.

– This is basically a Greek way of thinking, Tuv points out, before mentioning that the ancient Apelles is known to have painted in a rough manner. Thus, the rough manner of painting has always been regarded as more living as opposed to the stiffness in paintings that are outlined in detail without a focal point.

“Bathing scene from Åsgårdstrand” (1936) by Edvard Munch. Showing the painter’s decline.

Edvard Munch’s decline

When comparing the early works of Munch with those he made later on in life, there is a clear transition. Tuv and Thurman ask themselves the question: What happened with Munch?

– If you look at the grand scale of his life, it is very clear that there has been a philosophical change — that he actually had a change in his mind and therefore he is painting things very differently. To put it simply, he went from kitsch to art, says Thurman.

ON THE SHELF: Three stages of Munch’s career. “The Dance of Life”, “The Sick Child”, and “Bathing scene from Åsgårdstrand”.

He thinks Munch was negatively influenced by his friends, such as art critics.

Tuv points out that Munch was highly cultured and had an amazing talent, yet he went along with the fashions of the time.

– One would think that the two strengths that he had would be sufficient to protect himself from fashion. Munch is a good case study of what goes on if you don’t have your metaphysics, your sense of life, in order, says Tuv.

– Munch didn’t have his philosophy very clear. He had certain ideas, like when he painted Sick child, I think he had very clear Aristotelian ideas about how to make a great painting. But then, he gets this outside influence, which starts to create a battle. And so he wanted to turn towards modernism to be more accepted, Thurman adds.

Nic Thurman, interviewed by Jan-Ove Tuv for The Cave of Apelles.

Artification

To Thurman, it is important to make it clear that Art, as in Fine Art, was a term that came into existence in the 18th century. It was initiated by the wish to separate certain arts from mechanical craft:

– Their original purpose for doing that was that they wanted to be on an elevated level compared to those people, but the consequences were disastrous, because they introduced the idea that being in the fine arts, they had a certain spirit, as if it was a divine gift, explains Thurman.

At some point, Jan-Ove Tuv coined the term “artification,” which denotes a classical figurative painter who betrays his talent to be accepted in the value system of Art.

One can, for instance, paint a good face, before putting a dot on it or draw a line over the face, explains Thurman. Another example, Tuv adds, is to use very sharp, unnaturalistic colors in a figurative painting.

The painters who turn to “artification” are afraid of ending up as outcasts.

Tuv asks if Thurman has any advice to painters on how to tackle the situation of being an outcast, having difficulties to sell, etc.

– First and foremost it is the philosophy, to actually know what you are doing and what your goal is. And following that, it is all about the will. if you have the will to make masterpieces and you stick to that, and you don’t compromise with galleries or collectors or what have you, and you stick strongly to your values, then you will have success, says Thurman.

What is Kitsch?

According to Hermann Broch, the evil in the value system of art is kitsch. Why is the kitsch value system considered evil by people within the art community, and what are the values of kitsch?

– It is not a problem for Rembrandt to paint like he did, because that is what you were supposed to do at that time, says Tuv, pointing out what he considers to be the consequences of the Hegelian idea of the Zeitgeist — the spirit of time.

– In the art world, or the art value system, they are not concerned with the object. It is not about the painting at all. You see that when they praise works, and also when they call works evil, Thurman replies.

Tuv adds to Thurman’s point by citing the philosopher Tomáš Kulka: “Another difference is that kitsch does not inhabit any art historical space, that it is oblivious to what goes on in the art world. Kitsch ignores its competitors, it lives outside the context of art.”

Kitsch is faced with many accusations. One of them is that kitsch is a lie.

– Basically, when they talk about that it is a lie, they say that this is a vicarious experience, because it is just a fictional story, nothing is real here, and therefore, the emotions which it invokes are also not real, says Thurman.

This is completely untrue, he continues:

– Just because it’s a fictional story doesn’t mean that your sentiment or your emotions that are evoked by the story aren’t real.

A more pietist critique of kitsch is that it can arouse unethical feelings and emotions, such as being aroused when seeing a painting of a sensual woman. Thurman agrees that someone has an ethical problem with kitsch, but yet, he states, it serves its purpose.

– It is not as if you are going into this tragedy without expecting it to be a tragedy. So you’re not going into the unknown completely. The point of actually going there is that you’re going to have those emotions. Then, you can reach catharsis if it is good enough. So, if you have suppressed emotions related to the play, or emotions invoked by the play, then it is going to release those. And so you can go about your life with a certain relief or a relaxation for a while, he says.

Nic Thurman and Jan-Ove Tuv for the 16th episode of the Cave of Apelles.

The Cat

Tuv comes back to the philosopher Tomáš Kulka, and his example of how to paint a kitsch cat.

– He’s basically saying that if you are a kitsch painter, what should you do? And he lists the things that you should do and shouldn’t do, like Don’t paint washing machines – it has to have an emotional content, says Tuv and continues:

– And then he says that if you should paint a cute kitten, obviously, in order for the kitten to be cute, it has to look like a kitten. Then, imagine if the painter was so bad that the “kitten” just became blotches of paint – then, it wouldn’t be kitsch anymore. Right?

– Then I thought: “Well, what if it is not kitsch anymore, what is it?” Basically, it is describing abstract art, Tuv elaborates before concluding: The worse kitsch gets, the higher the art percentage gets.

Previously on the Cave of Apelles: The Kitsch Designer Eline Dragesund wants to Shape Men into Cathedrals

The Greek values

Tuv concludes by asking Thurman to sum up in what way kitsch represents the same value system as that of the ancient Greeks.

– If you look at the Poetics by Aristotle, then you will find these exact same aspects of kitsch, Thurman responds before listing some examples of Greek and kitsch values, opposed to the modernist Art values.

- Originality is not of much value — the opposite to the original genius

- The goal is to utter universal truths — the opposite to Hegel’s Zeitgeist

- In tragic paintings you should try to evoke feelings of pity and fear — as opposed to the Kant’s aesthetic indifference

Aristotle simply gives tips to poets, which in a way can be compared with the dogmas of the Memorosa Group. In the end, however, the thing of most importance is that poets study for themselves. That they study nature.

Thurman points out the necessity of aristotelian values to resurface in today’s society:

– Even as early as primary school, they’re teaching — not only in art class but also throughout the school — with a Kantian approach and they’re instilling those values. So one big thing would be to actually allow for this Aristotelian value system to be taught in school, Thurman says.

– And you’re part of the change, says Tuv.

– Yes, Thurman responds.

– Yes, we can, Tuv concludes smiling.

This article was first published at the Herland Report.

Published on Thursday, February 20th, 2020