News and Articles › Paintings and drawings

We cling nervously to the melody, but we don’t handle it freely, we don’t really make anything new out of it, we merely overload it.

— Johannes Brahms, composer

Top list

View the entire list

I had to make an important choice. I could hide in the background and work quietly, but no! I would guaranteed fall apart somehow. That is why I chose the raw and rowdy way — like Goya. The time I lived in was not for a Leonardo walking around and producing pretty studies. I have seen too many examples of our time’s distaste for the sensibly profane. That is why I chose the uninhibited. I wanted to do it in a grandiose way and stand on! I would rather take the chance and commit mistakes, with the risk of breaking my neck.— Odd Nerdrum interviewed by Jan-Erik Ebbestad Hansen in 1995-96 about his time at the National Academy in Oslo

The young Edvard Munch’s influence on his early years was not the only reason why Nerdrum’s paintings were rendered in such a rough manner throughout the 1960s. At age 15 he had discovered Goya’s “Chronos Devouring His Children” in a magazine and instantly fell in love with the horror and brutality of his pictures.

A recurring theme in Nerdrum’s body of work is the union between the beautiful and the grotesque. By his mid twenties, this aspect takes the shape of people run over by cars or shovelled away with combine harvesters.

SPOILER ALERT! This is the second in a series of six articles based on “The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum” (2018) which is available for streaming at vimeo.com/ondemand/oddnerdrum. I advise everyone to watch the documentary before reading this article.

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

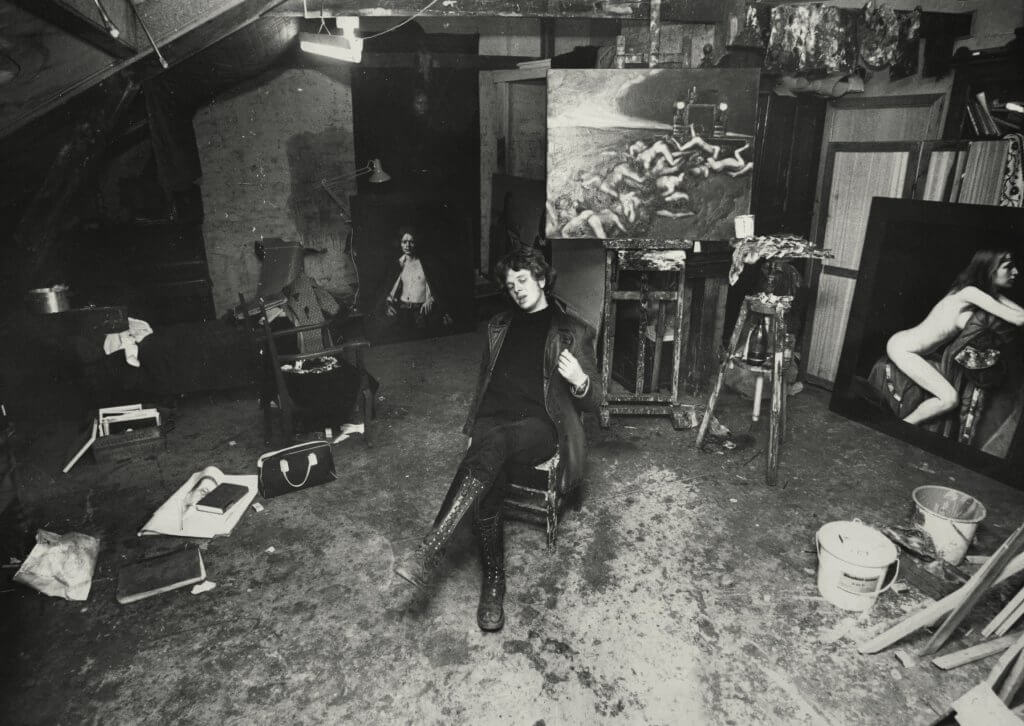

Odd Nerdrum in his studio in 1968. “Auschwitz” is hanging on the easel behind him.

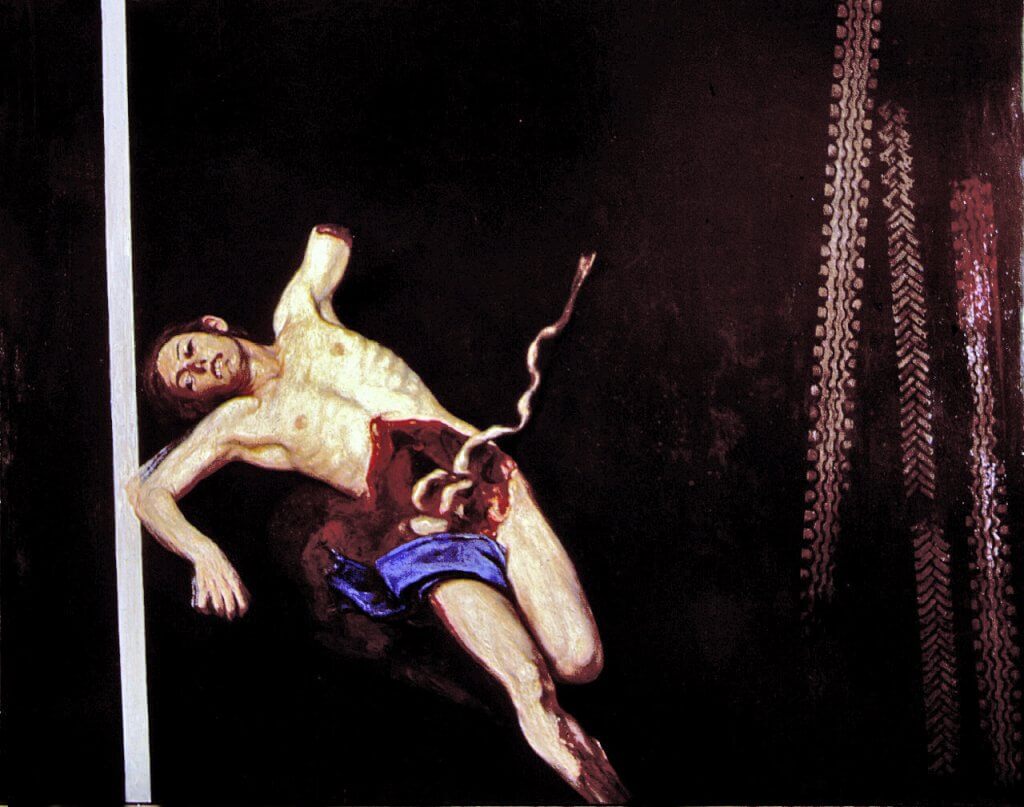

“Amputation” (1968) by Odd Nerdrum.Photo: Robert Meyer

With his painting entitled “Amputation,” Nerdrum put himself in the driver-seat of the romantic movement in Norway. The confrontation with human suffering in this picture bares resemblance with some of Goya’s works, such as “The Third of May,” and “Severed Heads and Limbs” by Théodore Géricault.

But neither a frenchman nor a spaniard would come to shake the very foundation of Nerdrum’s painting method and his ability to convey stories. For that, we need to look at an influence with origins further south in Europe that coincided with the student revolt that would pave the way for a period of terrorism in the Western World.

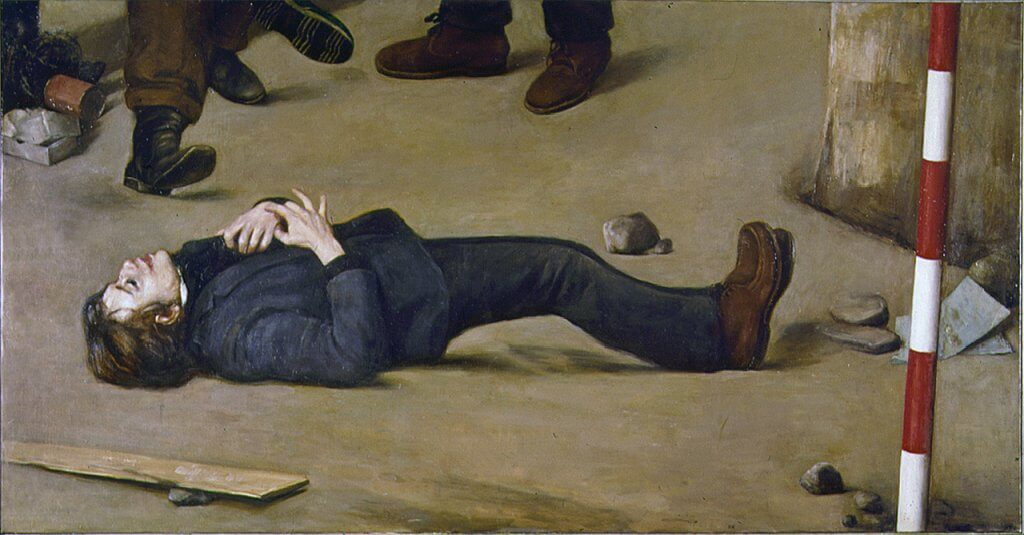

Auswich by Odd Nerdrum (1968?)Photo: Robert Meyer

A few years earlier, in 1964, Nerdrum had acquainted with the well-established sculptor, Joseph Grimeland, who had seen his younger colleague’s work in a group-exhibition at the Art Union. A meeting between the two at Theatercaféen in Oslo marked the start of a long-lasting friendship and together they discussed the idea of merging the classical tradition and contemporary motifs.

One of the markers in Nerdrum’s career takes place four years later when Grimeland invites Nerdrum to go to Italy to look at the masterworks from the Renaissance. They travel to see Titian’s “Pietá” in Venice, then Masaccio’s frescoes in Florence, and further on to Pisa.

But Nerdrum is not thoroughly contended with their journey and Grimeland has to conquer the leaning tower by himself whilst his companion takes the building into view from the ground.

Nerdrum feels that he has only been looking at pictures — instead of living through the grandiose moments.

At the next stop in the Eternal City, however, he has an epiphany.

A Masterpiece must consist of 85% Black

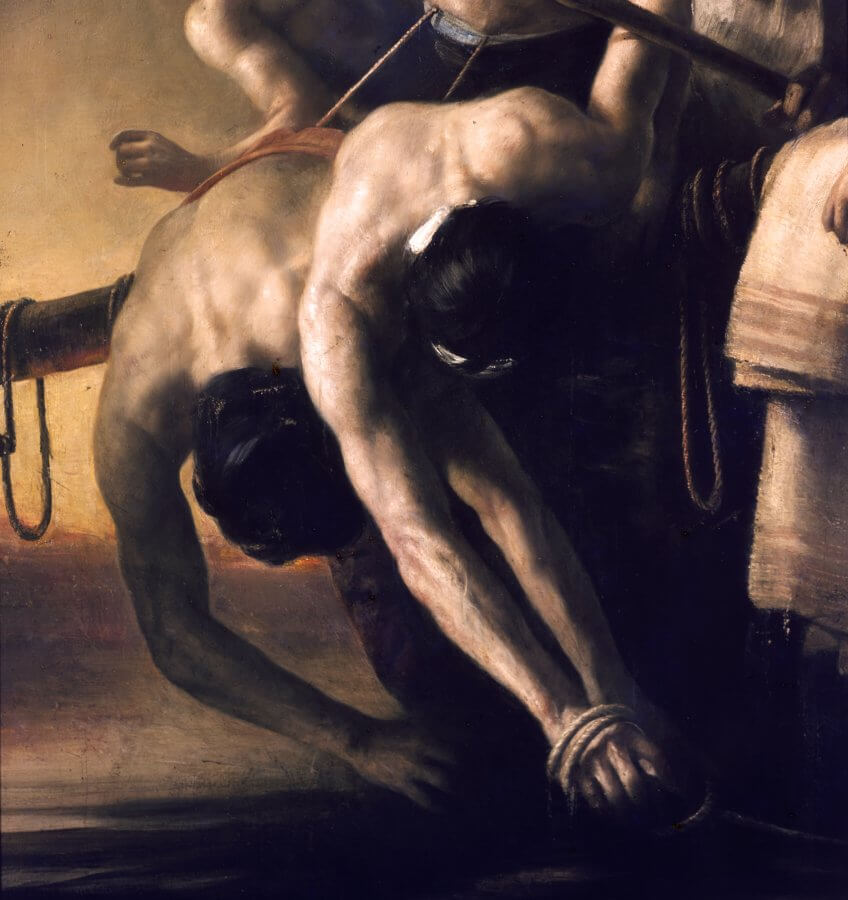

Near Piazza Navona in the Contarelli chapel of the San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, there are three grand paintings with scenes from the life of St. Matthew. Hanging on the right-hand side is “The Martyrdom of St. Matthew,” an outstanding composition with spiral-like movements that that has hung in the church since the turn of the 16th century.

The master behind this full-scale drama is none other than Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio; the rebel among painters who makes his fellow Italian men seem like sweet-tempered Scandinavians in comparison.

“The Martyrdom of St. Matthew” (1599-1600) by Caravaggio.

I brought some students here [Cerasi Chapel], and as we were studying these pictures, something struck me. Returning to Norway, I met Nerdrum and said that “I’ve now understood that a masterpiece must consist of at least 85 percent black.” And then he says, a bit nervous: “What percentage, did you say?! — Jan-Ove Tuv, from episode 2 of The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum

As he takes Caravaggio’s works into view for the first time, Odd Nerdrum is gripped by the grand theatrical drama in his paintings. “What happened,” he recounted decades later, “was an inexplicable recognition of something which is comprehensible. This was mine, something I had always longed for.”

The youthful expression in his dark church-decorations had some kind of Stendhal syndrome-effect on the 24-year-old Nerdrum, who instantly had to cancel the rest of the trip and go home to work on a series of new paintings.

It was The Martyrdom of St. Matthew that had caught his special attention.

“The cry is repeated in the face of the boy who is facing us, which actually is a precursor for The Scream by Munch,” he said and called Caravaggio’s painting “the dark archetypal scream.”

“Stefanus, The First Martyr” by Odd Nerdrum (1970)

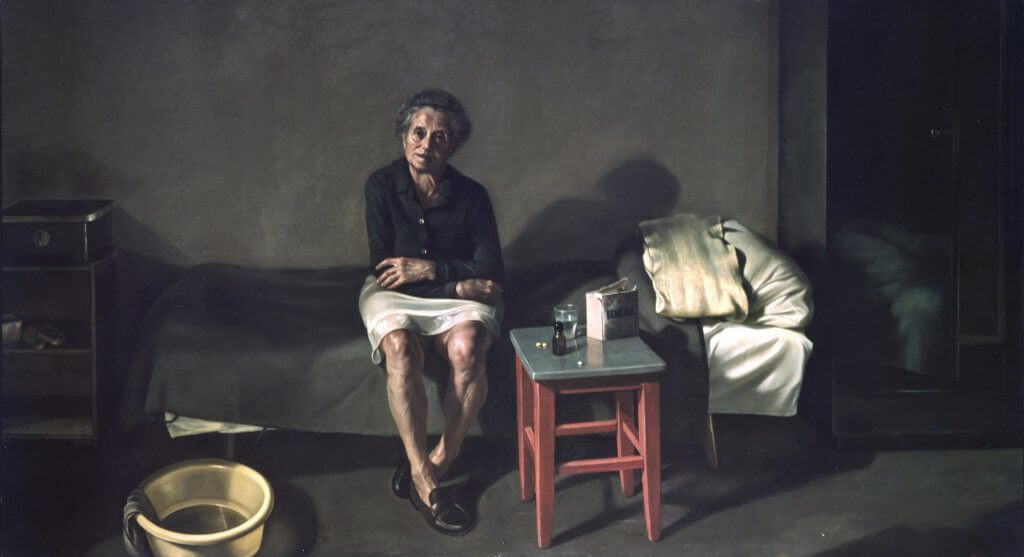

“Social Security” (1973) by Odd Nerdrum. In the collection of the National Gallery in Oslo.

In contrast to his earlier works, these paintings display sharper contour lines, and mark the beginning of a period of social-realism, where Nerdrum brings the classical expression together with scenes from contemporary life.

In my work I attempt — with the abilities that I have been granted — to make fundamental depictions of human beings from their everyday-lives. That is to say the parts of life that go unnoticed by the present time, which are nonetheless present. — Odd Nerdrum, interviewed by Lasse Henriksen in 1976

The up-to-date imagery prompts the National Museum to purchase several works, and for the first time, the critics’ reception is balanced.

The exhibition reviews that stem from this period, however, reveal a hope among critics that Nerdrum is developing into a “modern” painter. But Nerdrum has little to spare for his own time and he publishes several articles, attempting to diagnose the cultural paradigm of the West. In his essay, “Rationality and Art” from 1972, he points to science, technology, and the invention of photography as the causes for the fall of classical painting. But despite his pessimism, he goes on to say that “the blinding situation of mankind,” with its “foolish rationality,” and “peculiar contradictions in thought and movement,” could possibly open up for the visual arts in the future.

Portrait of a naked man by Odd Nerdrum. (mid 1970s?)

“Liberation” (1974) by Odd Nerdrum. The male figure’s posture is similar to that of the figure in Caravaggio’s “The Conversion of St. Paul.”

By the mid ’70s, Nerdrum narrows his focus down to pure skin-painting, as seen in the above examples. The faces are caught in the emotional climax of the scene and the painting-method, as well as the choice of composition, gradually become more similar to those of his role model from the Baroque.

He addresses contemporary issues related to sexuality, often taking central figures directly from Caravaggio’s postures.

The significance of a work of art is its ability to depict life. The life in it must emerge so strongly that the artwork enters into the background.— Odd Nerdrum, interviewed by Lasse Henriksen in 1976

The major works from this period no longer concern everyday events, but people’s conflict with modern society, and the position of the individual within the collective.

“The Arrest” (1976) by Odd Nerdrum. The posture of the central figure in the white shirt echoes the main figure in “The Flagellation of Christ” by Caravaggio.

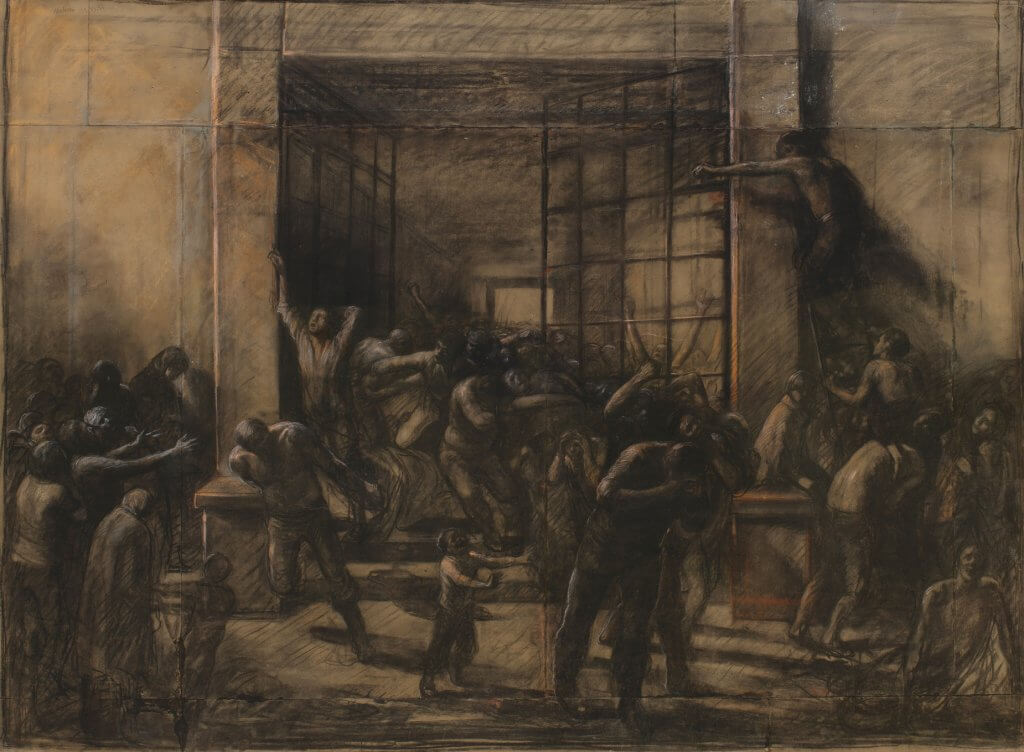

Sketch for “Opening of the Prisons”

The Murder of Andreas Baader

Throughout the ’70s, Europe is shaken by terrorist attacks, and with authors like Bakunin and Kropotkin on his bookshelf, Nerdrum, too, becomes engaged in the revolutionary atmosphere. He defines himself far to the left of other radicals, and shares his former teacher Jens Bjørnebo’s view on the outcasts of society.

When it is reported in October 1977 that the German terrorist Andreas Baader has committed suicide in prison, many react with scepticism, and Nerdrum starts working on a martyr picture of the RAF leader.

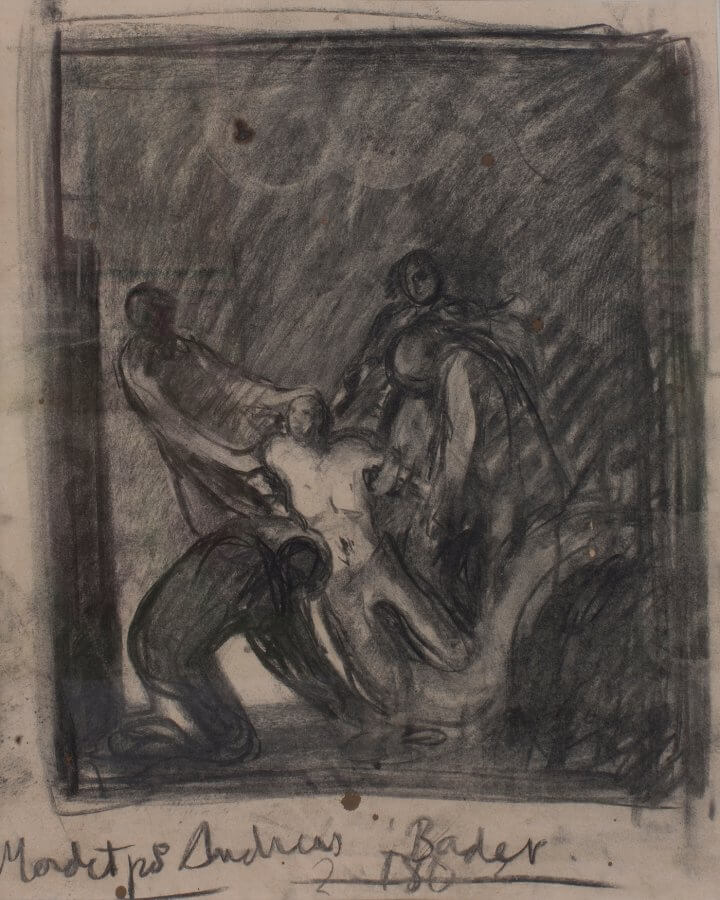

Sketch for “The Murder of Andreas Baader” (1978)

In the process, he visits a shooting range to experience firing with a weapon and discusses the Stammheim suicides with the businessman Trygve Hegnar, who models for the executioner.

The painting is kept secret in fear of reactions, until it is revealed at the Autumn Exhibition of 1978 in Oslo. But the painting receives no remarkable attention until an exhibition at the Culture House in Stockholm, a year later.

The Swedes are excited and the painting reaches newspapers far beyond Scandinavian borders.

In Norway, critics scold the picture as “murder in brown sauce,” and a “grotesque mishmash.” They find fault with the motif on a technical as well as ethical level — even the radical leftists question what they see as a glorification of terrorism.

The debate continues when the Haaland brothers want to buy the painting and give it to the University of Bergen. But the decorating committee rejects the offer, and despite the interest from the student council, uncertainty involving the installation of the picture prompts Nerdrum to withdraw his painting. The University of Bergen abruptly asserts ownership to the painting, which leads to a legal settlement where the Ministry of Education concludes that the government cannot lawfully claim ownership.

HEADLINE: “The Murder of Andreas Baader Reported to the Attorney General’s Office” — a heated debate about the Baader painting and the placement of the picture nearly ended with a lawsuit between Odd Nerdrum and the Haaland brothers.

“The Murder of Andreas Baader” (1978) by Odd Nerdrum. In the collection of the Astrup Fearnley Museum since 1996.

What was it about this painting that caused so much furore?

“The Murder of Andreas Baader” was painted at the time when the caravaggesque influence reached its peak in Nerdrum’s work. It is a typical St. Andrew’s Cross composition and the placement of the figures echoes “Crucifixion of St. Peter” by Caravaggio. Besides this influence, an interesting fact to consider is that Scandinavian painting has no tradition whatsoever for dramatic, narrative painting on a grand scale.

But when Nerdrum himself was asked to make a comment in the heated debate of 1979, he had a different angle. He said that “I don’t think they react to the old-master aspect of it, nor the title. The reaction has to do with the human drama and lack of irony.”

Chiaroscuro meets nature

A year after “Baader,” Nerdrum is able to finance a five-meter-wide dusk-image of victims of the Vietnam War. The idea of “contemporary drama” also characterizes this painting, but the motif has been moved out of the dark room, and into nature. “The Ferry” by Jakob Jordaens, which young Nerdrum saw in Copenhagen, illustrates the same mood that he tries to achieve in his own painting.

“Refugees by the Sea” (1979) by Odd Nerdrum

Detail from “Refugees by the Sea” (1979) by Odd Nerdrum

When “Refugees by the Sea” is completed, after half a year of intensive model studies, it has become the most complicated composition of his career. With his refugee painting, Nerdrum proved to himself that he managed to solve the most advanced compositions, technically, and he could consider the painting as his final certification.

From that moment on he could loosen up his technique and focus on other challenges. He claimed that his view of man had been problematic for a long time and expressed his thoughts about the painting six years later:

I will never make another picture like that [Refugees by the Sea], because not a single individual on board the fleet can guarantee for the quality I gave them. I transformed all of them to heroes, to beautiful saints seeking the good. But I have now come to a different conclusion. I do not think that man is good, but that he can become good. I cannot continue to sanctify one crook after another through my way of painting. The idea was naive.— Odd Nerdrum (Gateavisa, March 1985)

On this foundation he decided to leave nation, culture, and civilization once and for all, and cast humanity out into a brutal reality.

This is the second in a series of six articles based on “The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum” (2018) which is available for streaming at vimeo.com/ondemand/oddnerdrum.

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum

Deciding to track down Odd Nerdrum’s sources of inspiration, his former pupil Jan-Ove Tuv and his son Öde go on a world tour, visiting the museums and people that crossed paths with the painter in his pursuit of the immortal masterpiece.

Genre: Documentary Duration: 4 h 26 min

Subtitles: English, Spanish and Chinese

Published on Wednesday, June 20th, 2018