News and Articles › Movies Paintings and drawings show-home

Around the time Edvard Munch died in his home at Ekely in the winter of 1944 — Edith Marie Nerdrum was interrogated by Gestapo due to her husband’s involvement in the Norwegian Resistance Movement. Eventually, she managed to smuggle herself out of the country in a tank truck and gave birth to Odd Nerdrum on the other side of the border, outside of Helsingborg, Sweden.

Later, when Odd grew up in postwar-Norway, he was tutored at the Rudolf Steiner School by the anarchist writer Jens Bjørneboe, who took special notice of him early on:

I cannot imagine that any of our teachers have ever witnessed children’s drawings akin to those Odd produced during this semester. […] Odd is very self-disciplined, and has a hard time understanding that this does not apply to everybody else. […] He is gentle, dreamy and kind-hearted; in all aspects an exceptional boy.— Testimony written by Jens Bjørneboe, 1952-53

SPOILER ALERT! This is the first in a series of six articles based on “The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum” (2018) which is available for streaming at vimeo.com/ondemand/oddnerdrum. I advise everyone to watch the documentary before reading this article.

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

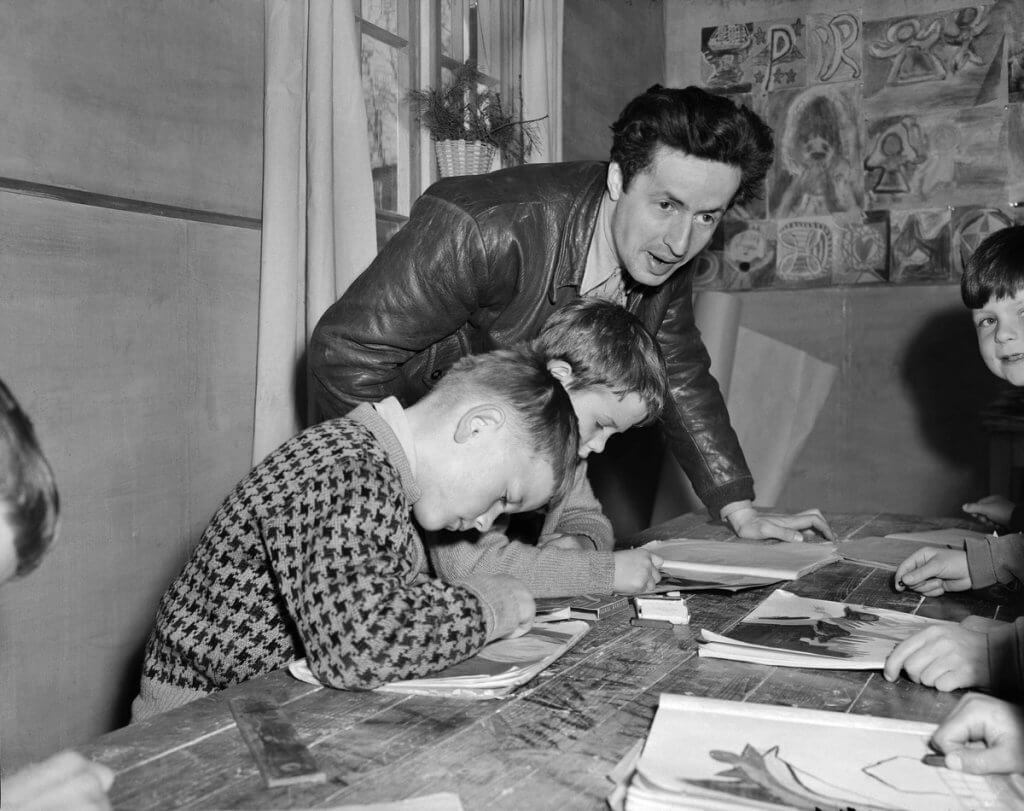

Jens Bjørneboe teaching at the Rudolf Steiner School in Oslo in 1952 Photo: Leif Ørnelund

Jens Bjørneboe photographed with his students at the Steiner School, probably from 1953. Can you spot Odd Nerdrum?

Around this time, Nerdrum’s stepfather takes him to the National Gallery in Oslo where he quickly sets his eyes on “The Sick Child” by Edvard Munch. This rough and melancholic painting — which bares resemblance with Rembrandt’s “Jacob’s Blessing” — is partly a memory of Munch’s own childhood, but the motif and the intensity he has captured in this picture is universal.

To put it in Nerdrum’s own words: “This work has been painted by a thousand sick hands.”

When Nerdrum is eight years old, Bjørneboe asks his students what they want to be when they grow up, to which Nerdrum replies: “I shall become the new Edvard Munch.”

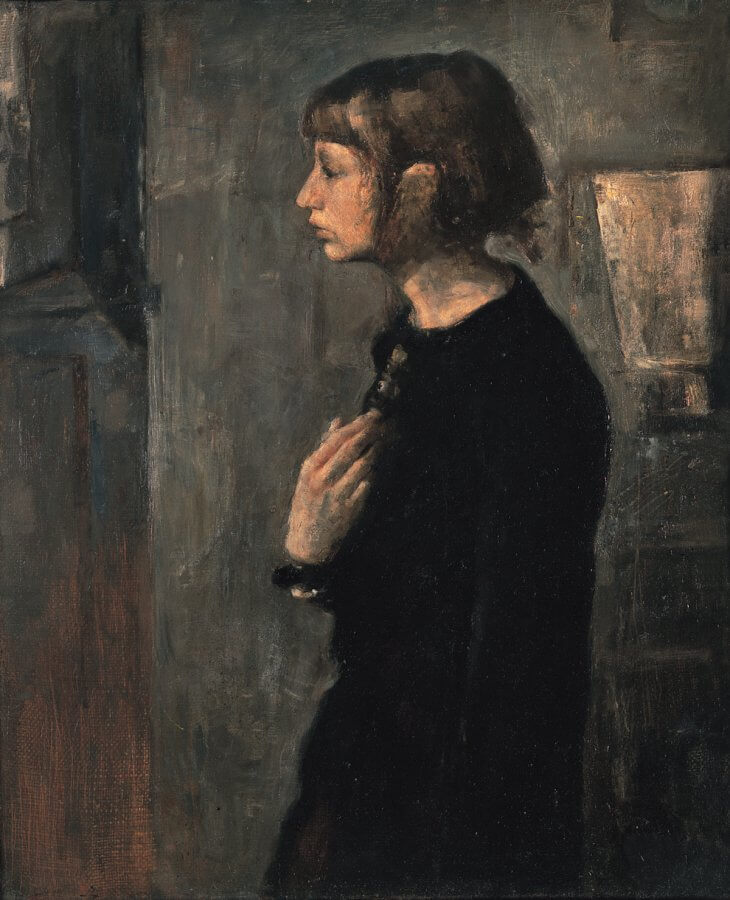

Ten years later, Nerdrum embarks on keeping his promises. The works he produces before, during, and after his short stay at the National Academy show a rough and subdued style of painting, familiar to the portraits done by the young Munch.

The portraits of young girls he made at that time… if you were to find them in a container 800 years from now, with a lack of historical precision, you would not be able to distinguish the two [Munch and Nerdrum].— Per T. Lundgren, interviewed for The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum

“The Sick Child” (1886) by Edvard Munch

Portrait Study by Odd Nerdrum — painted during his stay at the National Academy in Oslo in 1963.

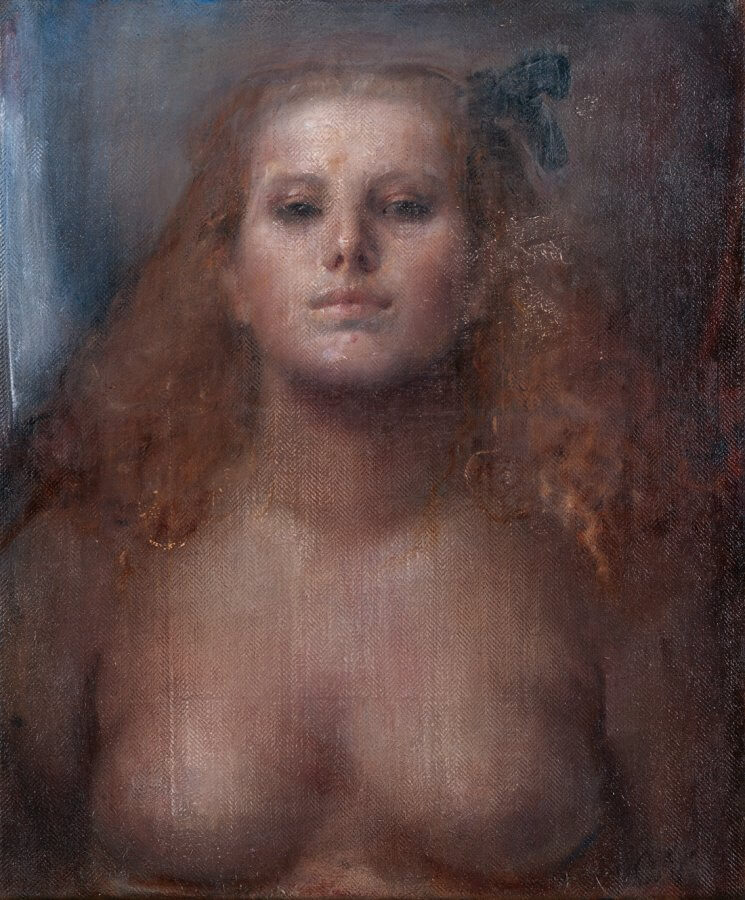

“Girl with Red Hair” (1966) by Odd Nerdrum

Photo of Odd Nerdrum in his late teens posing beside a self portrait hanging on the easel.

In the 1960s, the art world has more or less eradicated painting as a classical discipline within academies, and Nerdrum finds himself in a position where his love for the old masters is regarded as nothing more than a “protest” against contemporary aesthetics. His first solo-show at the Art Union in Oslo in 1967, generates the largest crowd rush to a contemporary painter’s exhibition in many years, although critics accuse him of pastiche, lack of anatomical knowledge, and of disobeying his own time.

But Nerdrum has a confident and sharp-tongued response to public criticism:

I have no compassion with poor people, but I have compassion with poor souls. I am therefore the Norwegian art critics’ very best friend.”— Odd Nerdrum, interviewed by Kåre Kivijärvi in 1967

One news paper article written by Øistein Parmann calls him a “young old master” when he exhibits his “Ikaros” at the Autumn Exhibition at the Artists House that same year and notes that “Some years ago it was still the mark of a radical to paint in a non-figurative manner in Norway. Today, most of the non-figurative painters represent the old-fashioned painting. They are our time’s ‘Düsseldorfers.’ And we see a whole group of our young painters turn their back on them.”

This movement of “our young painters” included names such as Tone Løvseth Ek, Karl Erik Harr, Frantz Widerberg, Arne Paus and Bjørn Ransve — many of whom would turn into abstractionists. Most of them were primarily influenced by Lars Hertervig’s fable landscapes which received recognition after the retrospective exhibition of his work in Oslo in 1961. Nerdrum was unfortunate enough to never see the exhibition, but he too was inspired by the Norwegian landscape painter and became the head figure of the romantic movement in Norway with his shameless imitation of the baroque masters. But even though Nerdrum painted landscapes directly inspired by Hertervig in the mid 1960s, he would not incorporate the mythical imagery of the 19th century painter into his work until twenty years later.

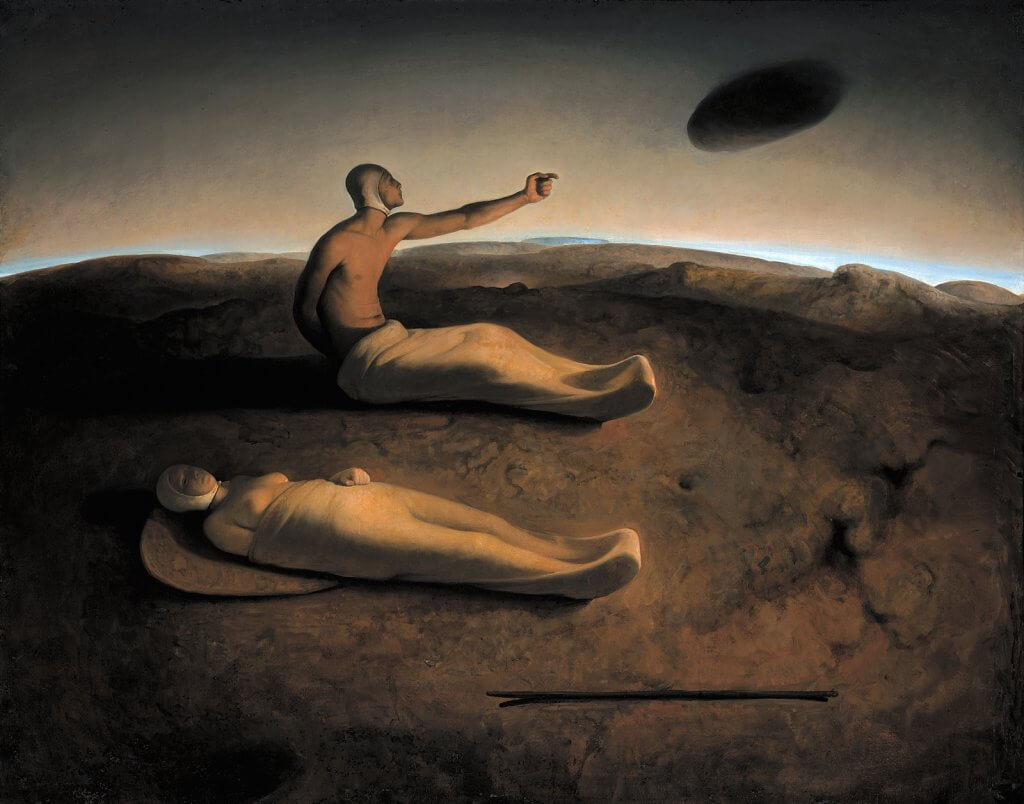

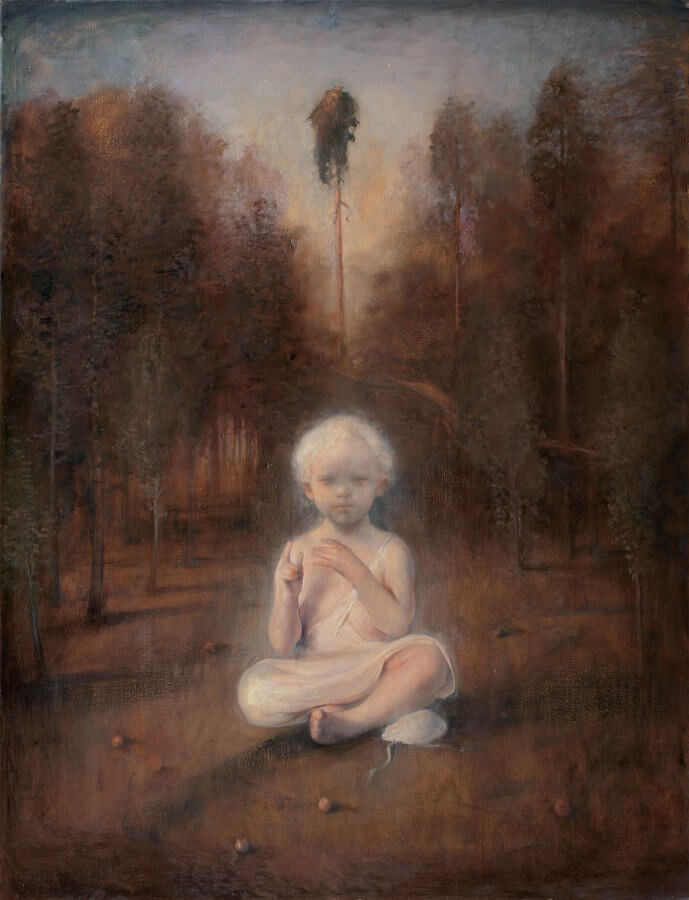

“The Black Cloud” (1986) by Odd Nerdrum

The cloud is man’s awakening dialogue with nature, because man has lost his language. Language has to begin anew, so that a cloud is a cloud, a tree a tree — you can almost name that cloud hovering the sky. What I am talking about is substance. I give each little object meaning. If you look at a tree, you can call it “Ole” and touch the tree to feel that it has substance. But if you call it “tree,” then “trees,” and then “forrest,” you remove yourself from its substance and you become like the modern human being who perceives everything in collective terms.— Odd Nerdrum, interviewed by Jan Åke Petterson in 1987

The Primal Landscape Painter

In the early 1980s — after a period of social realism — Nerdrum’s imagery took on an entirely different direction. In his new minimalistic compositions, his subjects were cast out into a barren landscape and mythologized by archetypal storytelling.

At the heart of this change was Hertervig’s individualization of nature, his way of highlighting even the tiniest object in a landscape and provide it with life and character.

Lars Hertervig, or the “Leonardo of landscape painting,” according to Nerdrum, was born outside of Stavanger, Norway, in the early 1800s to a deeply religious family. He was not the typical naturalist painter of the Romantic Movement in the 19th century; he played around with the landscape he saw in front of him in order to complete what nature herself could not bring to a finish. But Hertervig had to struggle with the world around him most of his life and he remained a social misfit until his unworthy death in 1902 as a poor, poor man, who glued bits of paper together for a drawing.

Many of his followers in the 1960s romanticized the “misunderstood genius” when Hertervig rose to some fame in Norway. Nerdrum was primarily interested in his peculiar representations of nature, and the delirious clouds and pine trees — shaped almost like human beings — are prevalent in his work throughout the ’80s and ’90s.

“The Tarn” (1865) by Lars Hertervig

“Old Pine Trees” (1865) by Lars Hertervig — a master of manipulating the perspective.

The painting that Nerdrum holds in the highest regard by the Norwegian landscape painter is “Old Pine Trees” (above) — arguably Hertervig’s most narrative landscape. A interesting feature in this painting is not just how the sky is pulled down to earth but also the distortion of the perspective. Immediately, nothing seems out of touch. But on the left-hand side of the picture there are two nearly invisible human figures walking up a hill, surrounded by trees. And upon a closer look at the size of these figures — in relation to the trees farther back and to those in the foreground — the proportions are totally absurd.

Madness was a condition Hertervig was diagnosed with when he admitted himself to a mental institution in 1856 after returning from his stay in Düsseldorf, where he studied with Hans Gude. Years later he found himself living at the expense of the workhouse and doing some service at a farm and a furniture shop, whilst painting in his leisure time.

But was he mad in reality?

Per Lundgren — a former student of Nerdrum’s and a follower of Hertervig — thinks that there has been a misconception among many to diagnose Hertervig as mentally deranged based on his fanciful sketches, which Hertervig probably would dismiss as minor attempts.

One story goes that Hertervig was painting in the outskirts of a forrest one day when his employees attempted to retrieve him to his social service on the farm. To this, he replied: “Look! It’s my father; he’s hanging from a tree in the thicket over there.” His employees realized that he was not of sound mind and as they left, Hertervig chuckled and continued to paint.

“Isola” by Odd Nerdrum. The cloud formations are inspired by Lars Hertervig’s fable landscapes.

“One and a Half” (2010s) by Odd Nerdrum

Hertervig and Munch are probably the nordic painters that directly inspired Odd Nerdrum’s work more than any others. A deficiency they both had in common, however, is that they lacked human drama and storytelling in their work. Nerdrum once pointed out that Norwegians are on the whole more concerned with poetry of nature as they lack the southern temperament, a temperament that dominates Nerdrum’s paintings from the 1970s.

Part two in this article-series will cover the period before the Hertervig-influence, which saw its crescendo in Nerdrum’s “Murder of Andreas Baader.”

Click here to read the next chapter.

This is the first in a series of six articles based on “The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum” (2018) which is available for streaming at vimeo.com/ondemand/oddnerdrum.

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum

Deciding to track down Odd Nerdrum’s sources of inspiration, his former pupil Jan-Ove Tuv and his son Öde go on a world tour, visiting the museums and people that crossed paths with the painter in his pursuit of the immortal masterpiece.

Genre: Documentary Duration: 4 h 26 min

Subtitles: English, Spanish and Chinese

Published on Friday, June 8th, 2018

I was not aware that the painting Murder of Andreas Baader was one of his works. I recall that work back when I was a US soldier stationed in Germany back in the late 70’s that painting had an effect on me and I remember it but haven’t thought about it over 40 years and now that I’m researching Odd Nerdrum I find he was the artist. Seems to indicate I’m on the right road with my research.

What a little shitrock is the way to make the money