News and Articles › Cave of Apelles

If the embodiment of the fundamental idea of our age were to be found in Victorian architecture […] then our age would undoubtedly be called the ‘age of kitsch.’

— Hermann Broch, author

Top list

View the entire list

Co-founder and former Academic Director of the Florence Academy of Art in Gothenburg, Joakim Ericsson, is a creator of fantasy worlds and peak moments. In the Cave of Apelles, he shares his story of how he went from being a classical painter and successful instructor to becoming a digital painter working in the gaming industry.

When Jan-Ove Tuv asks where his interest for science fiction and fantasy came from, Ericsson can point to an exact life-changing experience that took place when he was five years old:

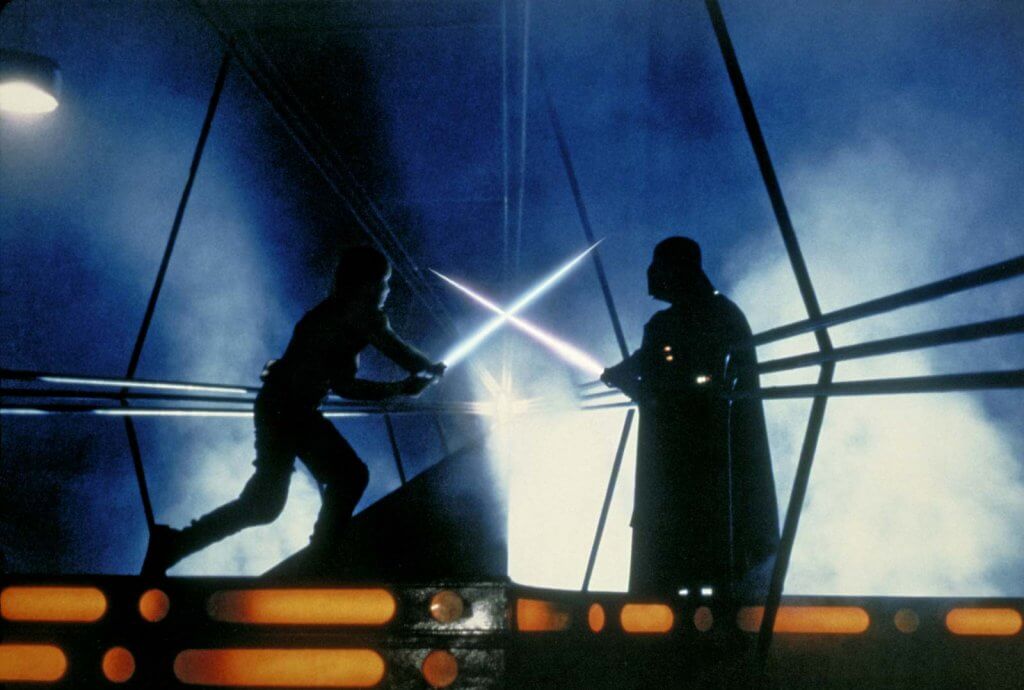

When the first Star Wars movie hit Sweden in 1977.

– In that moment, my life was changed. I was completely mesmerized. I was obsessed with it and drew Darth Vader and Stormtroopers for years and years, says Ericsson and continues:

– From that [moment] on, I preferred to live in that fantasy world than to live in the real world.

Would you like to be credited as a supporter in future videos?

Donate now

“What… this is a guy who is alive today?”

After having received a preparatory education at The Stockholm Art School at age nineteen, Ericsson decided that he wanted to pursue a career in painting. But several years of frustration and confusion would follow. He applied to several academies but did not get accepted anywhere.

– I got a job in the library in the Royal Art Academy in Stockholm. One task was to register returned library books, says Ericsson and continues:

– And one day, there was this big dark cover of a book saying “Odd Nerdrum.” It was written by Jan Åke Pettersson.

Ericsson thought that it was an old master whose work he had not seen before.

– Instead of filing it and putting it back into the shelf, I started going through it, wanting to see all these amazing paintings, says Ericsson, remembering that he was shocked that he had not heard of the painter before.

Then, as he read the description of the paintings, he realized that he was looking at a contemporary painter. He was stunned, thinking: “What… this is a guy who is alive today?”

– That was like the Star Wars moment. I was completely blown away, because I thought I was the last idiot left on earth who wanted to work in this way.

– So did you apply to the Nerdrum School?, asks Tuv.

– I realized that I am going to contact this person one day, and try to figure out if I can study with him, but first I have to get better, answers Ericsson.

L’Innocence by William-Adolph Bougueareau Photo: Christies

A Flyer from Florence

While improving his painting, Ericsson continued working in the library. One day, as he was sorting mail, he coincidentally came across a flyer from the Florence Academy of Art.

– I could see right away that this was the only place I knew about where I could go and learn what I needed to learn, basically.

In the fall of 1998, Ericsson moved to Florence, Italy and received a three-year program of academic training at Daniel Graves’ school.

– It’s a very strict curriculum they have, says Ericsson when being asked about the academy’s way of teaching.

He explains that it is much about learning accuracy in the beginning – especially in regards to drawing, values, and edges. The students start out using black paint. Later, they may add white to their palette. Gradually, they are allowed to expand to other colors.

– Florence Academy tries to reestablish the 19th century academic tradition, but most of that knowledge was lost, says Ericsson.

The Pink Egg

After attending the Florence Academy, Ericsson thought his skills were sufficient to finally apply to the Nerdrum School, so he sent Odd Nerdrum a letter.

– I was like a man waiting for his death sentence, Ericsson remembers.

But he did not wait long. Two days later, he received a letter in return. Nerdrum liked his work and invited him to come to study with him.

Something that struck Ericsson when he attended the Nerdrum School was that Odd Nerdrum could start a painting in a way that to someone who has limited experience would not make any sense whatsoever: – With his experience and talent, he has really no restrictions in terms of technique.

Odd Nerdrum working on his composition “Arch”. Photo: Öde S. Nerdrum

He recalls the first painting he saw Odd Nerdrum paint.

– It was a blank canvas. Only the gray surface. […] he had a big blob of salmon pink on the palette, and he just dipped his fan brush in this. Then, he just painted a big pink egg on the canvas. Then, he stabbed the fan brush in pure black, and made two dots for the eyes.

Ericsson says that he was looking around for the candid camera, thinking “What the hell is going on?”.

– It looked so bizarre. It was just this pink egg with two dots.

“I have better starts than that” he thought, somewhat cocky. But after about an hour and a half, the tables had turned.

– By then, I was almost crying because all of a sudden he had taken this pink egg and developed it into this amazing form, amazing drawing, amazing color – everything was there!

Although shocked by the method, he understood Nerdrum’s method: doing everything at the same time.

Co-founding FAA in Sweden

After his time at the Nerdrum School, Ericsson went back to Florence to teach and when the academy opened a new branch in Gothenburg in 2006, he was appointed as its academic director — a position he held for ten years.

– One of the things Daniel Graves told me when I started teaching was that that’s the first time you will realize what you know and what you don’t know, because if you are not able to explain it to a person, you don’t know it.

Teaching for one and a half days a week, Ericsson enjoyed being a mentor for his younger colleagues. They solved problems together, improving the students’ work as well as his own.

But the position of academic director also meant that Ericsson had to deal with a lot of paperwork and bureaucracy. What he thought was just the startup face, turned out to be an endless challenge.

– I completely underestimated how much time and energy that would take. […] To be really honest, he [Andreas Birath] took most of the practical work, so it could’ve been much worse for me.

But in the long run it took too many hours away a week, I think.

Joakim Ericsson: “The Burning Horse” (2012), Oil on canvas, 115 x 125 cm.

Joakim Ericsson: “Alone in the Wasteland” / “Lilith” (2012), Oil on canvas, 110 x 145 cm.

Returning to childhood

While serving as the academic director, Ericsson’s work started shifting more towards fantasy imagery. His childhood, playing role-playing games, and living in the dream of Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings, had haunted him for quite some time.

– In my own work I started to make more imaginative paintings, like The Burning Horse. I realized that I don’t want to paint another still life in my whole life. I just got so fed up with still lives.

– I remember when you had painted The Burning Horse, Tuv replies, – How you managed to get that extreme coolness of the warmth where it’s hottest. This is really storytelling and painterliness coming together.

In 2012, Ericsson exhibited his burning horse and “Lilith” (based on Babylonian mythology), at an international show in Florence.

He recalls that he had looked at them and thought “these are actually the two best paintings I have ever done”.

The exhibition would prove, however, to be the defining moment for Ericsson’s decision to end his career as a painter.

– Six months later, I am sitting in my studio, and “Lilith” and “The Burning Horse” are wrapped in bubble wrap, unsold, collecting dust. It just felt like the imagery that I wanted to do, is not really wanted in the gallery world.

Ericsson resigned his position at the Florence Academy of Sweden, he stopped painting, and entered the gaming industry as a digital painter.

Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader in “The Empire Strikes Back” (1980) Photo: Mary Evans Picture

– When I switched digitally, my motifs switched as well. Because I started making illustrations rather than paintings.

Tuv remarks that in the fantasy genre, one has more options to be timeless, pointing to the introduction of Star Wars: “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…”

– Yes, replies Ericsson. – If you have a sci-fi or fantasy universe, you can strip away all that noise that can be distracting for the story.

Joakim Ericsson: “It is Time” (2017), digital illustration. Source: Art Station

This article was first published at the Herland Report.

Published on Sunday, September 15th, 2019