News and Articles › Philosophy

I often hear classical figurative painters refer to The Allegory of the Cave by Plato – of course – always in a pretentious manner – as they think themselves to be among those who see the world for what it really is.

It would be an understatement to call this connection strange; it is as paradoxical as anything could ever be. Why is this so? The answer is clearly given in the allegory itself.

The Allegory

In Book VII from the Republic – Plato provides us with a dialogue between Socrates and Glaucon (the pushover that Plato wants you to be).

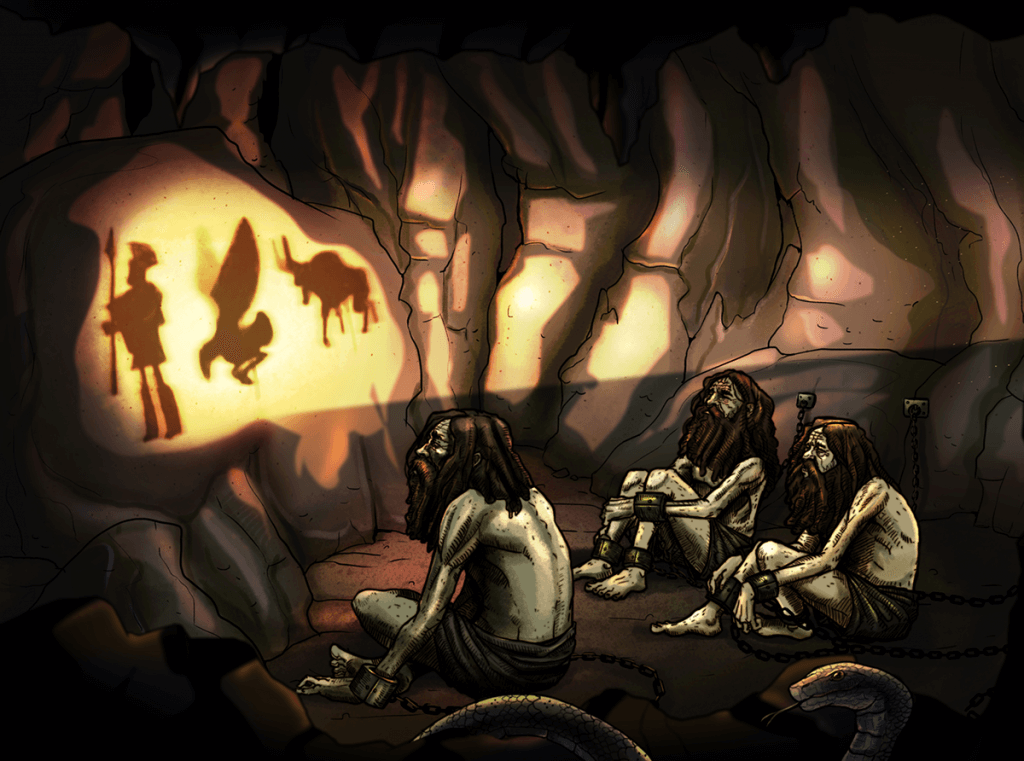

In short, Socrates tells the story of an underground cave where human beings are chained to necks and legs, forcing them to have their eyes fixed on a wall of moving shadows. The shadows, which are shaped as animals, are merely the shades of puppets controlled by marionette players in the background.

Socrates goes on to explain how much distress it would cause someone to be unchained and released out into the real world above and Glaucon replies “yes, I agree” to everything.

The allegory itself is fine. Plato’s conclusion, on the other hand, is disturbing.

According to Plato, the shadows on the wall represents the world of sight:

This entire allegory, I said, you may now append, dear Glaucon, to the previous argument; the prison-house is the world of sight, the light of the fire is the sun, and you will not misapprehend me if you interpret the journey upwards to be the ascent of the soul into the intellectual world according to my poor belief, which, at your desire, I have expressed whether rightly or wrongly God knows.

– Socrates, Book VII (The Republic by Plato)

It is strange that Plato – who called the world of sight a “prison-house” – would allow someone to make a portrait of him at all… does not that make him a hypocrite?

Aftermath

Plato’s attack on the sensory world in The Allegory of the Cave is just one of many.

In Book X from the Republic – in another dialogue between pushover-Glaucon and Socrates – Plato dismisses poetry altogether as an imitation of an imitation and he calls for a general ban on all poets that do not limit themselves to producing political propaganda.

The real world – in Plato’s view – is the world of ideas. But this noumenal world cannot be comprehended by human beings.

Aristotle – who was Plato’s student – has the exact opposite approach to philosophy. While his teacher would say that music and theatre deprives people from doing there duty as citizens – Aristotle would accept the joy of entertainment as a part of human nature and he would try to elevate music and theatre to their highest state.

All of this leaves a BIG question mark:

Why is it that so many classical figurative painters and sculptors hail Plato’s allegory – when each and every one of them would be doomed to a life in exile under the rule of his philosophy?

Published on Friday, November 10th, 2017

`music and theater deprives people from doing there duty as citizens`

I believe the solution to your dilemma consists of delineating between entertainment and art; the former debases, whereas the latter elevates.

This is a very powerful analogy.