News and Articles › Philosophy

Art teaches us to see into things. Folk art and kitsch allow us to see outward from within things.

— Walter Benjamin, literary critic

Top list

View the entire list

Imagine the film industry with an ‘artistic’ mindset. It would no longer be an industry, as the audience would not attend cinemas to be entertained. Film-directors would base moviemaking on arbitrary action, and reject the idea of competition in favor of pursuing self-fulfillment. After all, who needs an audience to affirm whether or not one’s succeeded when an art police can make those decisions instead?

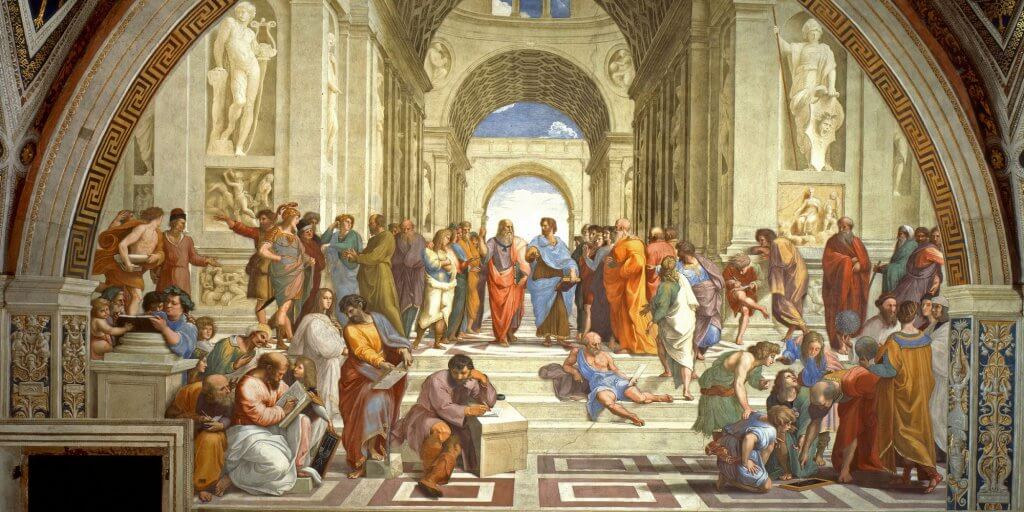

But ‘artistic’ ideas have yet to infect the film industry – an industry rooted in theater developed during the golden period in ancient Greece. Movies are not made for the sake of self-fulfillment or innovation. They follow the strict rules delineated by Aristotle’s Poetics and exemplified by tragedies like King Oedipus. In Hollywood they say: “Make it the same complex family drama – only different”. There are certain ways in which things are done and certain techniques that work, and these are favored over those that do not. From the film industry to the art world, distinctions are clear-cut – largely because each can be traced to two thinkers:

The first is Aristotle. He is the father of Hollywood, and the writer of the most influential book on poetry called Poetics – known for a strong belief in the empirical nature, and for a rational use of the Greek word ‘techne’ (meaning “skill”, “science” or “discipline” that can be taught and learnt, but mistranslated by many to ‘art’ in its modern sense).

The second is Immanuel Kant. He defined and formed fine art as we know it today, by promoting what has been called a “Copernican turn”: instead of studying the object (e.g. a painting), one should study the evaluating mind (subject) to find out whether a work of art is beautiful or not. Instead of learning from each other’s opinion, only one judgment is valid: the pure taste (a priori).

So, why the success with Hollywood but the flop with art? The answer is found in ten central distinctions:

1. Originality

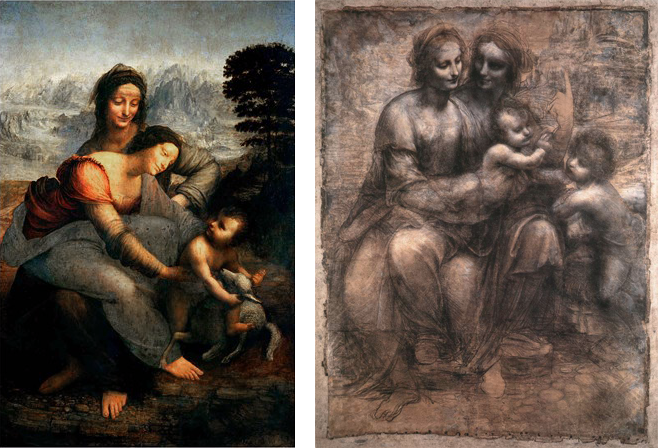

Let’s say a painter wants to remake St. Anne by Da Vinci – with the intention of making a better work than the original. This endeavor would, according to Kant, undermine “the idea” behind the original. In addition, Hegel would deem the poor man an outlaw for betraying the duties to his time. In contrast, a moviemaker could successfully remake Romeo and Juliet, given its basis on the natural rules of tragedy – and at best, make it even better than its forerunners (said to be more than a thousand!). Movie-directors do not, as artists, make movies to utter their own voices, but to reveal universal truths, irrespective of whether it’s been done before – as long as it’s of high quality…

Da Vinci himself remade several of his own paintings, including Mona Lisa and, not least; St. Anne (drawing), and the later painting of the same subject. (Left: The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, Right: The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist)

2. Plausibility

The Godfather is a story told and screened convincingly. If a movie aims at being true to life (or convincingly realistic), but fails to do so, the fault cannot be forgiven. Even figurative painters today are working in ways Aristotle would never tolerate, due to lack of plausibility. With symbolic depictions of animals and human beings in peculiar postures and objects tied together which never could be combined in real life; these painters belong more to fantasy than to poetry. According to Aristotle, a painting which contains impossibilities ought to make the viewer believe that it could happen, because this would bring it within the range of reason. The whole point of art, however, is that the product should not be credible to life.

STORYTELLING: If it works for Hollywood, then why not for painters too? (Image: a snapshot from Chaplin’s The Kid)

3. Storytelling

“But this is an obvious one,” you say, “of course a movie should tell a story, but things of that kind have nothing to do with art”. Quite right, as art is about design. Again, there are figurative painters who do not follow the ideas of Aristotle, as they take for granted that storytelling is something found in movies – and not paintings. In the movie-business the movie is the means and the story is the end. Modernists are of the opinion that art should be both the means and the end. As the Kitsch-painter and teacher Jan-Ove Tuv remarked after looking through a book on impressionist painters: “The only time a figure was depicted with an open mouth, was when the model was yawning”. Caravaggio is a prime example of a painter who almost could not avoid the narrative in his works, producing one historical painting after another. Human beings love to be told stories, and this is the main reason why they are drawn to movies and theater.

4. Irony

Although Hollywood produces comedies (which naturally are ironic), the industry does not have a problem with the more earnest forms of drama, and why should they? Tragedies are higher esteemed than comic movies, and have a greater tendency to become classics. Movie-genres are not a question of right or wrong, but a question of market. In art, right and wrong are as present as in religion, and an artist cannot be anything but ironic, as melodrama and sentimentality belongs to the more low-ranked and ‘kitschy’. Aristotle characterizes comedy as a distorted mask of ugliness, and as a representation of people that are inferior, while tragedy as a representation of superior and noble human beings.

5. Comparing

It’s a natural thing to compare; humans make comparisons of movies all the time, and these judgments create competition. Competition is forbidden in the art world, as great works are “beyond comparison”. A painting is in other words autonomous. Without competition, however, one would have a ruling opinion – commanding people to like this and to like that, without consideration of outside convictions.

The Prodigal Son by Rembrandt is poetically represented, and shows us something we know. You do not have to hold a close relationship with your father to like this painting, as it’s a universal depiction of an embrace between two human beings. (Image: The Return of the Prodigal Son by Rembrandt)

6. Identification

A basic rule in Hollywood is that the viewer must identify with the hero in the picture (if there is one), or in general with the dramatic events. Aristotle states in his Poetics that representations appeal to us because in representation we recognize something we’ve seen before, as opposed to something unknown. This ‘unknown’ – or divergence – is clearly visible in the art world, where direct identification between the spectator and the work is nonexistent. But a representational painter, yes, even a semi-representational painter has already committed himself to an objective principle.

7. Beyond the surface

Plato believed in a world outside our own – a true and unchangeable reality of ideas. Kant belongs to this tradition, with his “thing in itself”, which cannot be reached with our senses, but only graspable through pure taste and produced through genius alone. He described it as “the soul of the work” – Something beyond the surface of, e.g. a sculpture. But talking about the soul of a Hollywood movie like Gladiator would be absurd, as its aim is to evoke emotions of pity and fear. Thus it follows that people do not watch the movie to search for that which they cannot see.

8. Pleasure

Kant said that a work should neither be produced through enjoyment, nor taken in delight by the viewer. Attending an art-show seems equivalent to going to Sunday church, demanding a quiet contemplation, walking from one empty white-walled room to another. Cinemas are rather dramatic, with dark rooms, and aim at producing astonishment in the audience. On one side there is Kant, explaining all that is forbidden – while Aristotle, on the other, reveals the tricks of how one can succeed in one’s virtues, and impress one’s audience through “deceivable” features, such as –

When watching an excellent movie, is there ever more than that which meets the eyes and ears? (Image: a scene from Gladiator)

9. Décor

Sophocles was the first writer in ancient Greece to introduce scene painting to theaters, and was praised by Aristotle as the only playwright to use the choral element as a part of the story taking place on stage. He called staging an emotionally attractive attribute to a play. But, do not such attributes belong more to the scene painter or the musician, than to Sophocles? Kant demands the writer, or perhaps the painter, to stand naked in front of us with his art, excluded from disturbing features such as picture-frames, which rather interfere with our truthful consideration of the object. But what would movies be without the decorative musical element, provided by composers like Bernard Herman and Hans Zimmer? This source of intense pleasure, according to Aristotle, is a viable quality which Kant considers the least artistic form, as its only target is to please our senses.

10. Reason

To explain why a movie is well made is perfectly reasonable, but forming an opinion about a painting based on objective rules, is all of the sudden excluded. This difference is crucial. Aristotle, the father of reason, was also the father of Hollywood, with his short writing on poetry. Logic is found in how a movie scene is made, and the ways in which plots are constructed. It’s all about “what works.” The art world is different. From the genuine, to the unimaginable, to the unknown, and finally, to the noumenal world, Kant has neglected every logical route of deriving an explanation. Imagine now the art world with Aristotelian principles. It would no longer be art, but kitsch – according to the definitions of the two terms. If the art world functioned according to Aristotelian principles, museums of modern and contemporary art would be filled with visitors, just as movie-theaters are filled with people seeking entertainment. In exhibitions, paintings would be framed and presented in dark rooms with dramatic spotlights, in order to trigger the audience – indeed, why not include some music too? No more excuses for paintings to please on their own account, but competitions and prize winning awards to the most lifelike imitations, as in ancient Olympic Games. To paraphrase Ayn Rand – with Aristotle’s philosophy, we could have the greatest renaissance yet to be seen on this planet.

In his book Titian and Tragic Painting, Thomas Puttfarken argues it was Aristotle’s Poetics that changed the late Titian’s course in his work, not his increasing age. (Image: Detail of Titian’s Pieta)

Returning to poetry

Generally unknown, Aristotle’s Poetics first took on popularity in the 16th century, which became the work’s high point, and, according to art historian Thomas Puttfarken, inspired and caused the change of Titian in his late lifetime. Titian was certainly struck by Aristotle’s idea of elevation – to imitate the human form, but complete what nature could not bring to a finish. Might Aristotle have written his book in defense of poetry from other threatening ideas? Similar to his successor, Immanuel Kant, Plato emphasized the extra-sensory world, which to Aristotle was no more than an abstraction. Aristotle held that you have to look at the horse’s properties and what can be its use before you begin to look for what is behind it. But for Plato, poetry was less “authentic” than nature, as it was an imitation of an imitation. Consequently, poetry caused more evil than good to man and thus ought to be banished for the sake of “truth” – the “true” world behind our own (Plato’s Republic, Book 10). But what happens when civilizations favor the unseen to life on earth? Was it not this belief that induced the Christians to tear apart the Hellenistic culture – and the inventory of catholic churches during Luther’s reformation? (English translation by Anne Herrero)

Published on Thursday, July 30th, 2015