News and Articles › Paintings and drawings

One of the characteristics of kitsch is precisely the neutralization of ‘extreme situations’, particularly death, by turning them into some sentimental idyll.

— Saul Friedländer, historian

Top list

View the entire list

In 1990, Nerdrum visits the Titian exhibition, “The Prince of Painters” in Washington. By this time, he has been through many stages of painting, from Hertervig’s understanding of form and Caravaggio’s clair-obscur technique to Rembrandt’s glowing skin painting. Now it was time to return to the dissolving style he had experimented with in his youth, with Titian’s late technique — dubbed “pittura di Macchia” by Vasari — as his new role model.

Titian is the first free painter who paints directly on the canvas without under-paint. He has used a pretty rough canvas with herringbone pattern, giving the painting its own beauty in the structure. After he had finished preparing it with dark ochre, he waved around with the brush, a bit disjointed, flickering, to then finally collect it to a whole. The painting has of course many “mistakes.” One example is that the nymph’s legs are way too small. However, it is the incredible overall feeling that makes him the world’s greatest painter. — Odd Nerdrum, commenting on Titian’s “Nymph and Shepherd”

Nymph and Shepherd (1576) by Titian

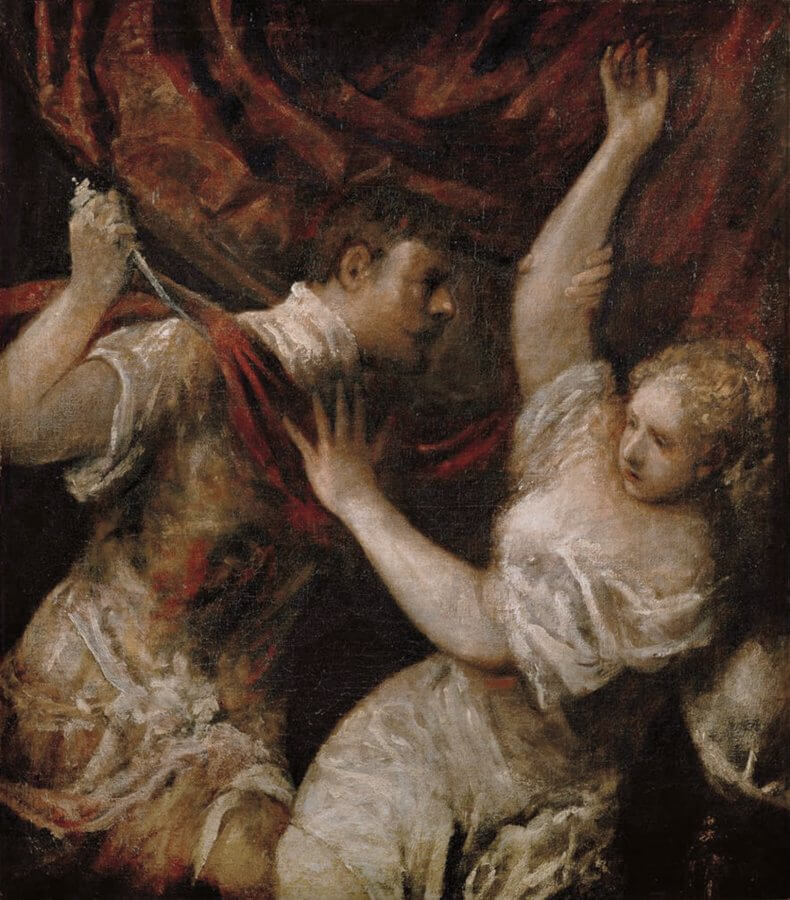

Tarquinius and Lucretia ( 1571) by Titian

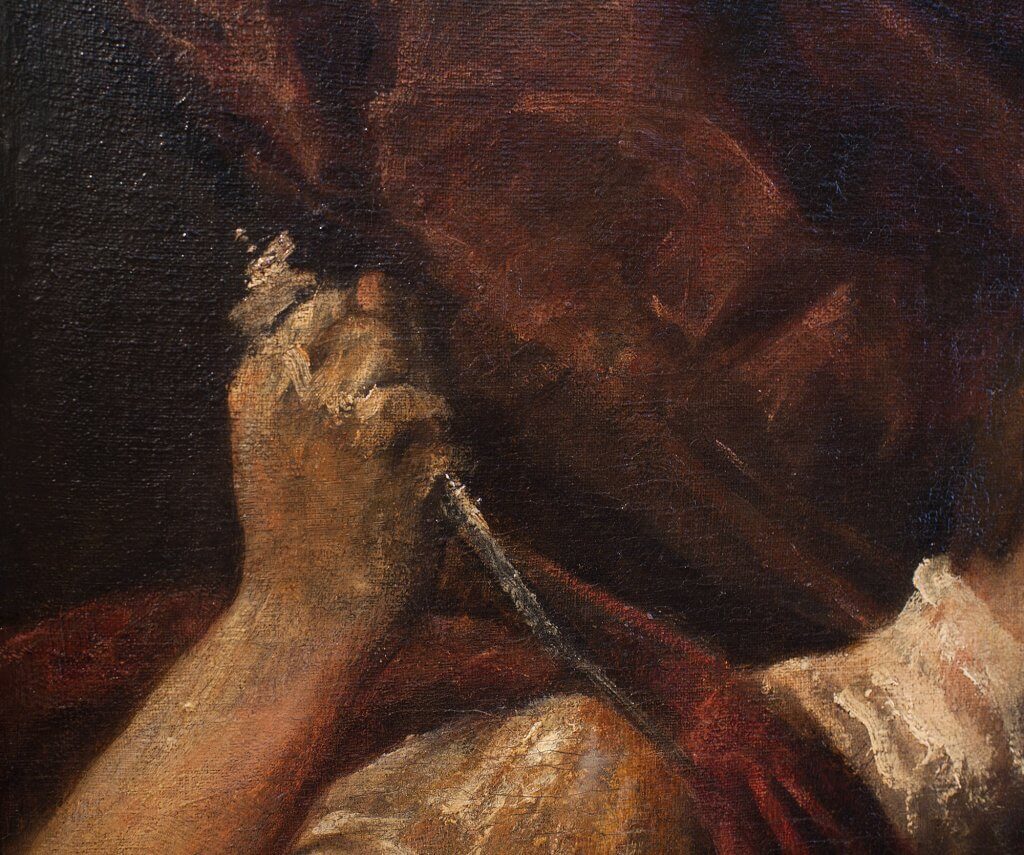

Detail from Tarquinius and Lucretia ( 1571) by Titian

As with Nerdrum, Titian’s mythical figures are placed in nature. Cloth folds, colors, tears, and blood are subdued so that the focus is on the facial expressions and the narrative of the painting. The “underworld mood,” with the sun as a vanishing point in the horizon is one of many attributes of the ageing Titian which has been of interest to Nerdrum in the last few years.

The figures are often naked or covered with loose pieces of cloth on a sketchy background. Despite the sometimes weak execution of hands and feet, he is exquisite in the details, and supposedly, a big part of his late production was made without the use of a brush.

Historians usually claim that the rough style was due to the painter’s failing sight and weakening arms. On the contrary, other historians have affirmed that the rough style was intentional, that the method is not a precursor for Impressionism, but originates from an older handcraft tradition.

But who inspired Titian to paint in the dissolving style?

It is time to take a trip to Italy to look at the painter who not just influenced Titian and Caravaggio, but also the works of Nerdrum.

SPOILER ALERT! This is the fifth in a series of six articles based on “The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum” (2018) which is available for streaming at vimeo.com/ondemand/oddnerdrum. I advise everyone to watch the documentary before reading this article.

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

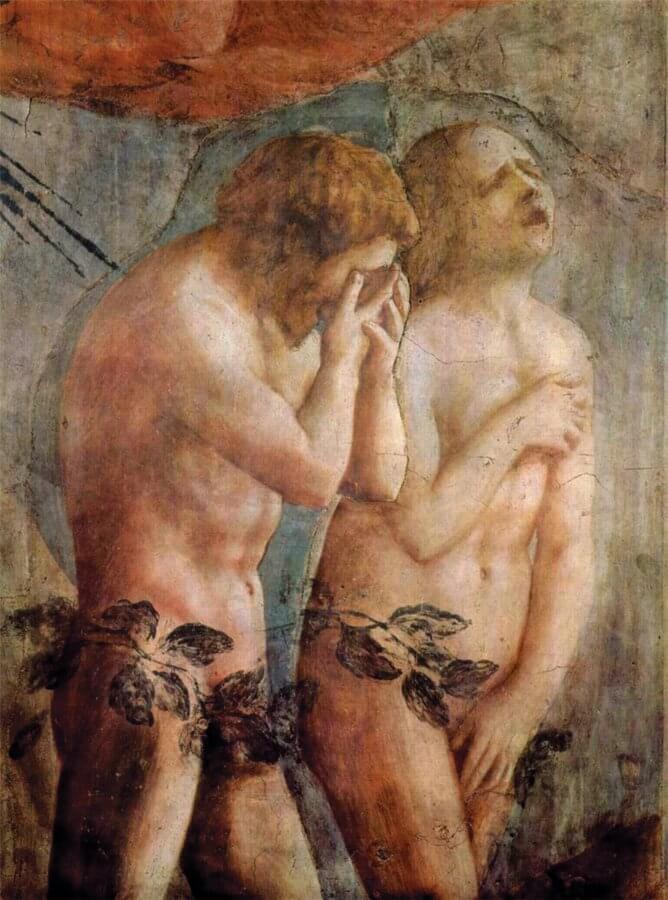

Adam and Eve (1425) by Masaccio. This photo was taken before the cleansing of the chapel in Florence.

The First Humanist Painter in Europe

Masaccio is often regarded as Giotto’s successor and initiator of realistic painting in Italy, a hundred years before the High Renaissance. The frescoes in the Brancacci chapel display a humanism that, in the year they were painted, had been unseen since antiquity. The work was started by Masolini and finished by his 18-year-old colleague who would surpass all painters during his time. The rough perception of form is clearly visible despite the conservation work done in the 1980s. But the frescoes have undoubtedly been damaged by the restoration. Picturesque transitions have been removed and the works, as a whole, have become flat and garish.

According to Nerdrum, who saw the chapel prior to the cleansing, elements of the dirty appearance have always been present in the works of Masaccio, which Titian might have seen more than a hundred years after their conception.

Masaccio is one of the first who softened the strict medieval rules. A realism that made it necessary to work much more than previously with the paintings. Before, no image was supposed to surpass nature: God’s creation. But then came the Renaissance, and one began to put the world underneath oneself. This is a transitional work towards the great mimetic period in which they imitated nature, a period that began in the Renaissance and gradually ceased in the 1890s. — Odd Nerdrum

In 1428, Masaccio dies at only 26 years old. Little is known about his life, but legend has it that he was poisoned by a jealous colleague during his stay in Rome. Perhaps Masaccio’s humanism came to early for an Italian culture not quite finished with the Middle Ages. But while contemporary society did not value the Florentine painter, the future generations would be forever grateful. Verrocchio, Botticelli, Leonardo, and Michelangelo, all based their work on this chapel, which, according to 16th century biographer Vasari, displays the first lifelike imitations in European painting.

In the summer of 1546, when Titian is passing through Italy on his way to Venice, he visits Florence and is greatly impressed by the city’s wealth of painting and sculpture. Eventually he loosens up his paintings, a method he would take to such a high level it may not have been reached since. Titian, who was widely known for his sense of details and coloring, became a laughing stock towards the end of his life due to his smudgy, dim paintings, and the students who imitated him did not have the experience to handle the effect.

Dissolving in a Mythic Landscape

When Nerdrum adopted the rough technique in the 1990s, the purpose was to make new paintings look like they had been made centuries ago. The pictures are scraped down with sandpaper, giving a sense of motion to the surface. In contrast to the sketchy works from his youth, these pictures are marked by decades of Rembrandt-inspired brushwork and the solidness of Caravaggio.

Five Singing Women (2002) by Odd Nerdrum

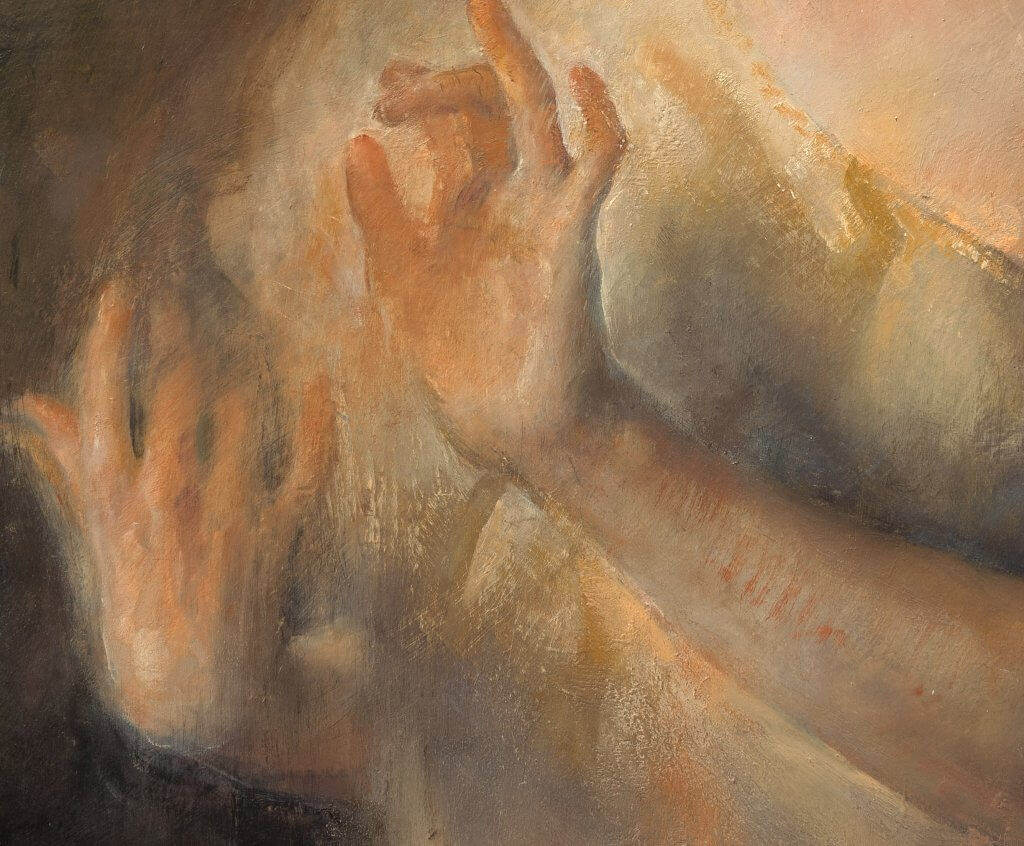

Detail from Five Singing Women (2002) by Odd Nerdrum.

A turning point in Nerdrum’s dissolving style is the nearly four-meter-wide painting “Five Singing Women.” Here, the Caravaggesque strictness has been replaced by a foggy effect, in which the transitions between flesh and background are merged. Light vibrates throughout the entire composition, just as in the last works of Titian. To a higher degree than before, the model is an impersonal being, which, together with the crazy perspective, enhances the timeless expression.

When Nerdrum painted this picture he had withdrawn from the public and he soon moved to Iceland where the motifs were pushed out into the universe.

In the following period, the paintings increasingly loosen up.

Tourettes (2011) by Odd Nerdrum

Detail from Tourettes (2011) by Odd Nerdrum

A Long Tradition

Masaccio, Titian, and Rembrandt have in their respective centuries worked in the dissolved tradition, which Nerdrum continues in the 21st century. From where the technique originates, however, remains a mystery, which Masaccio’s frescoes on their own, do not fully reveal.

First: detail from Adam and Eve by Masaccio — second: detail from Pietá by Titian — third: detail from Simon in the Temple by Rembrandt — fourth: detail from Memorosa by Odd Nerdrum

Up to the 1540s, the works of Titian are characterized by symbolic content. As the Greek myths take over his narratives, the figures move out into a dramatic landscape that resembles the underworld. Even motifs with religious content get a touch of humanism, which separates them from similar depictions at the time.

Titian’s close friend and comedian, Pietro Aretino, writes his first tragedy during these times, just one of many examples that intellectual life in Italy is changing. But what was it that made writers and painters in the 16ht century interested in the tragic? And why where they increasingly depicting stories from myths instead of historical events? To better understand, we must take a look at the philosopher who defined a world of ideas, including imitation and pathos, long before “kitsch” existed, and who would lay the foundation for the Renaissance.

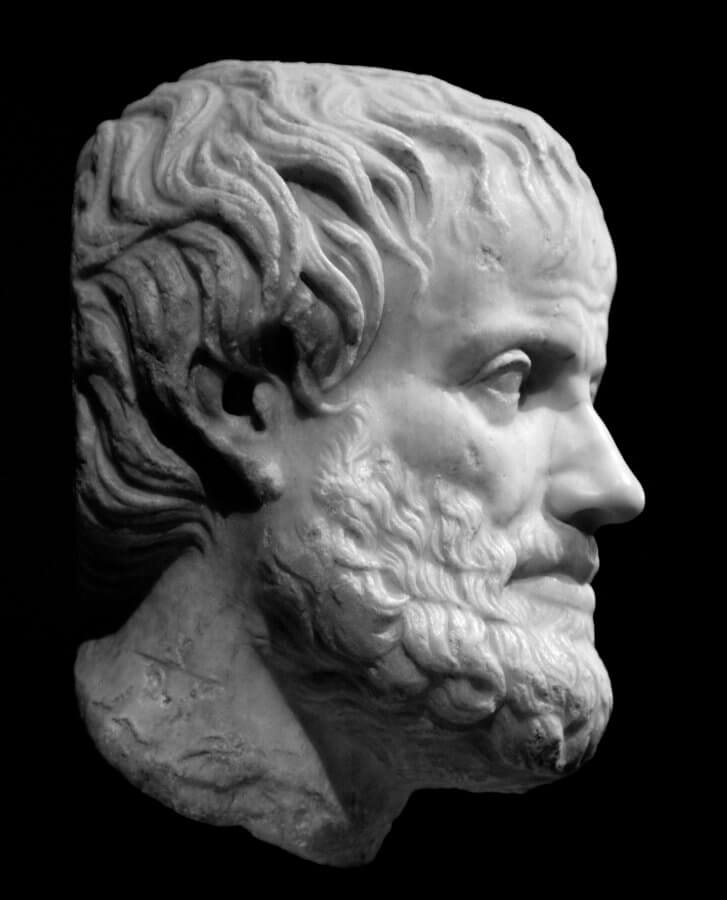

Bust of Aristotle, Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

The World’s most Influential Writer on Poetry

Aristotle was a scientist and empiricist who lived in Greece, 300 years before Christ, and is considered by many to be the most significant philosopher in Western history. In contrast to his mentor, Plato, who rejected the rational reality, Aristotle is only concerned with the world of the senses.

Though a large part of his work is destroyed after his death, the Greek philosopher has his glory days in 16th century Europe, when his treatise on poetics comes to the forefront of cultural life in Italy. In “The Poetics,” Aristotle writes that imitation is the main characteristic of a poet. The spectator takes pleasure, not in the original, but the recognizable aspects in the depiction. Further, he claims that all imitations must serve a purpose, as for poetry, that means to portray universal truths about humanity.

According to the German historian Thomas Puttfarken, Titian likely studied “The Poetics” and other writings of Aristotle as he developed the rough technique. Above all, Puttfarken points out the importance of drama. The sketchy effect in the works of Titian becomes, in the Aristotelean sense, not a goal in itself, but a means to serve the storytelling in the picture.

The Flaying of Marsyas (1576) by Titian

To reinstate Aristotle in culture could lay the foundation for a turnaround in the perceived usefulness of painters and sculptors. Today, storytelling is evident in cinema, something that could also have been the case for painting and sculpture if the philosophical prerequisites for the craft had been different.

When Nerdrum embraced the kitsch concept in the 1990s, it was an attempt to leave the idea of art for art’s sake. With the influence of Titian he has taken a decisive step in this direction. What Masaccio started in the 15th century has led to a classical tradition from which Nerdrum has handpicked the essence of European culture. It can be argued that all development stops when the level of late Titian and Rembrandt is reached, that the idea of Pre-Impressionism in the Renaissance was always an illusion to raise the modernist above that which came before.

But is there still a possibility… a method of taking it yet another step further?

Beyond the old masters.

This is the fifth in a series of six articles based on “The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum” (2018) which is available for streaming at vimeo.com/ondemand/oddnerdrum.

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum

Deciding to track down Odd Nerdrum’s sources of inspiration, his former pupil Jan-Ove Tuv and his son Öde go on a world tour, visiting the museums and people that crossed paths with the painter in his pursuit of the immortal masterpiece.

Genre: Documentary Duration: 4 h 26 min

Subtitles: English, Spanish and Chinese

Published on Tuesday, July 3rd, 2018

THANKS MASTER, I BELONG TO THE CATEGORY OF WHO IS STOP IN PAINTING BUT YOUR WRITINGS HEAT ME THE HEART