News and Articles › Paintings and drawings

Kitsch is the great hedonist vehicle of our time.

— Philip Crick, author

Top list

View the entire list

For more than 2000 years, the Western Classical Tradition has overcome some of the darkest ages in history.When Nerdrum left social-realism in the 1980s, he had seen that contemporary elements obstructed his archetypal message. Contact between nature and man has since been reinforced by the four-color palette, and the rough technique of Titian’s late paintings. Like his predecessors, Nerdrum has built on the idea that one can always improve. Leonardo, Titian, and Rembrandt enjoyed dramatic improvement towards the end and died in front of their major works.

But the Western Classical Tradition, of which Nerdrum became a part in his teenage years, did not have the Renaissance as its source. Transparent draperies, naked people with harmonious proportions and half-dreamlike faces, are some of the aspects that characterize a different epoch farther back in history.

What is the very cornerstone of Europe, then. The Greco-Roman culture? This is what has made us humanists, where knowledge is our greatest source of pleasure. The Greco-Roman individual takes pleasure in viewing and understanding an object, while an art-individual seeks to reveal the reason for how and why they are personally affected by the object. Everything that is going to last forever, as they say, is the Greco-Roman culture. — Odd Nerdrum, TRAC2014 in Ventura

SPOILER ALERT! This is the last in a series of six articles based on “The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum” (2018) which is available for streaming at vimeo.com/ondemand/oddnerdrum. I advise everyone to watch the documentary before reading this article.

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

You See We are Blind (2011) by Odd Nerdrum

The Dawn of Western Civilization

In a distant time… at the border of the Oriental World, Western civilization was born around 500 BC, in Ancient Greece. The archways, columns and armless statues that remain, testify to the reckless treatment of Athens, which on several occasions fell into Persian hands. Coming from a reality of war, plague, and destruction, the Athenians created a society which encouraged thinking and individualism. Sculptors and painters such as Zeuxis, Apelles, Myron, and Lysippos worked here in an age which placed the craftsman above the official. In an age which saw the birth of democracy, with philosophers such as Socrates and Aristotle. It was in the stronghold of this city, around 2500 years ago, that the classical culture would change the world for all future time.

Athens, Greece. View of Acropolis.

Parthenon at Acropolis, Athens. The temple is dedicated to the goddess Athena.

Parthenon, located at Acropolis in Athens, was erected by Ictinus and Callicrates in the age of Pericles, and is one of the most impressive constructions from the Golden Age of Greece. The temple arcs along the doric orders to the foundation, and does not reveal a single straight line in the construction. The reliefs were carved out by Phidias, who is generally credited with the sculptures of the pediments, including two gigantic statues of the goddess Pallas Athena.

Paintings by Polygnotus were exhibited to the public on the walls of the gateway, which had remained unfinished since the Peloponnesian war.

Taking the Roman Pausanias’ travel writing into account, one can conclude that Polygnotus’ works resembled Phidias’ Parthenon marbles. Like Apelles, he is supposed to have used few colors, and may be the first painter to make faces with open mouths and wrinkled eyebrows.

The major buildings at Acropolis include Erechtheion, the Temple of Athena Nike, and Parthenon, which is the highlight. Following its conversion into a church and a mosque in the Medieval Period, it was severely damaged during the Morean War in the late 1600s, when an ammunition storage exploded.

The Parthenon Marbles by Phidias. The ruins were brought to England by Lord Elgin in 1801 is now on display at the British Museum in London.

The classical architecture of Acropolis has continually been the backbone of European building techniques. In the 15th century it was mixed with the Gothic style, and has since been continued in the Baroque, the Rococo, and the Romantic Period, until the dissolution in the 20th century. The principle of harmonious proportions, however, has not been dominant throughout the ages. Several thousand years of history prior to the Hellenes has in large part left us with primitive sculptures and paintings from civilizations that inexorably have expanded, and vanished. In Antiquity, a few historic events would come to refute every assertion of a constantly developing world.

The Beginning of the End

The Battle of Corinth in 146 BC, marks the end of the Golden Age of Greece, and the rise of the Roman Empire. Under Roman dominion, the Greek ideal is transformed into Realism. Ennoblement of the model, with elongated torsos and godlike faces, is replaced by a reality-constrained depiction. The new style quickly becomes dominant in the Mediterranean, and 200 years after Christ the sensuous imitation of the human body has all but ceased to exist. The busts of the emperors are stripped of sentimental content, showing kinship to rigid Egyptian statues. Apart from some style reactions, the emaciated eyes reveal the resignation of the times. The Roman style is gradually replaced by hard-lined heads with rigorous face, which signals the beginning of German Antiquity, and 600 years of Dark Ages in Europe.

Following Christianization under Constantin I, and the Germans’ entry into Rome in the 400s, Greek cultural treasures come into the hands of the Middle Ages.

The once tolerant society of Rome becomes subject to vandalism. Bronze and marble figures are disgraced, by the lopping off of limbs, burn marking, and elimination. Pantheon is converted to the Orthodox faith, whilst other temples are left in ruins.

From the Sacred Chair in Rome to Jerusalem, the Christians destroy almost all trace of the Greeks, destroying the library of Alexandria, and a millennium of recorded knowledge.

“Course of the World: Destruction” by Thomas Cole

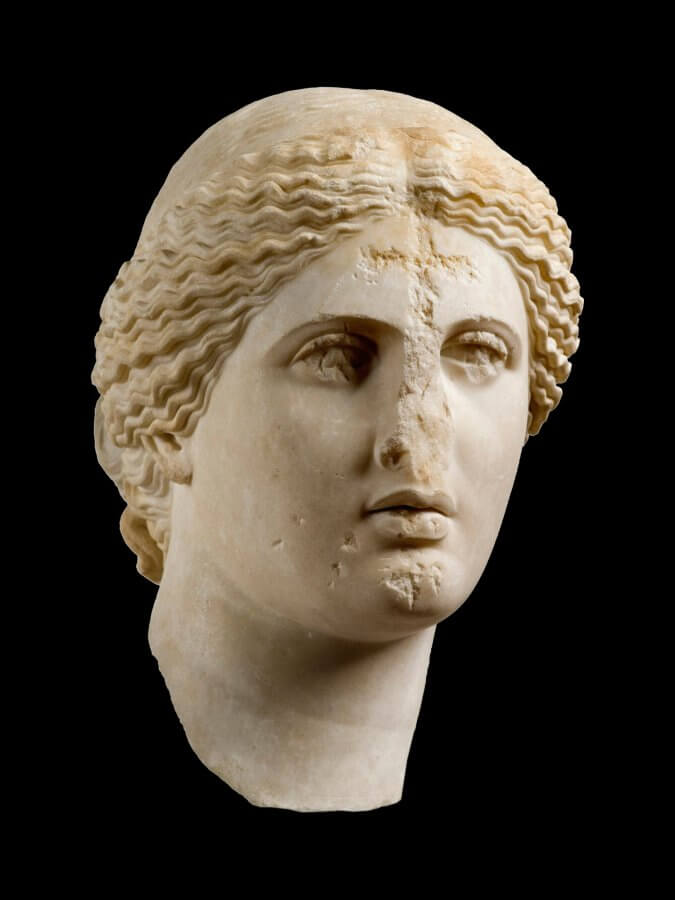

Head of Aphrodite. Greek, 1st century CE. Marked with a cross on the forehead.

The Resurrection of Antiquity

As Europe awakens many centuries thereafter, the self-extinction has had enormous consequences. A golden age of sculpture, architecture and painting is lost for eternity only to be replaced by some of the greatest sufferings in human history.

In the 11th century, ancient writings are rediscovered, which survive the Medieval Period due to the Islamic civilization and the Byzantine Empire. The ideas of Aristotle are unified with Christianity by Thomas Aquinas, and from Germany to Italy, cathedrals inspired by Antiquity rise from the ground.

In the 15th century, Greek temples are re-erected by architects such as Brunelleschi, Michelozzo di Bartolomeo, and Leon Battista Alberti. The sculptors contend in enlivening the Hellenistic ideal.

In 1506, Michelangelo becomes witness to the uncovering of the Laocoön group on a vineyard in Rome. Later he sees the Belvedere Torso, and recreates it in several figures on the Doomsday Fresco in the Vatican.

Painters, sculptors and architects in the Renaissance are perhaps the greatest imitators to walk the face of the Earth. With Leonardo da Vinci and Tiziano Vecellio, the 16th century marks the peak of European culture, and the rebirth of humanism in the Western World.

Left: the Belvedere Torso (c. 100 BC). Right: detail from The Last Judgment by Michelangelo

When Nerdrum grows up, half a millennium later, civilization has undergone dramatic changes. Towers and arches are replaced by flat, concrete buildings, which reflect the deviation from imitation of nature in the 20th century. Sculpture and painting has intentionally become subject of sloppy handcraft and metaphysical abstractions. The viewer has got a distant relationship to the work.

They play for you a play of boredom. It’s very interesting to have used boredom to attract the public. In other words, the public comes to a happening, not to be amused, but to be bored. — Marcel Duchamp on the daddaists, BBC Interview in 1968

Immanuel Kant’s portrait painted by Döbler, 1791. German Prussian philosopher, 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

The prevailing thought is that Modernism arose as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution and the invention of photography. However, intellectual currents dating back to the early 1700s tells a different story. A book which reflects the philosophical movements at the time is Immanuel Kant’s “Critique of Judgment.” In paragraph 46, Kant writes that “the Genius cannot indicate scientifically how it brings about its product, but rather gives the rule as nature. Hence, where an author owes a product to his genius, he does not himself know how the ideas for it have entered into his head, nor has he it in his power to invent the like at pleasure, or methodically, and communicate the same to others in such precepts as would put them in a position to produce similar products.”

The philosopher Hegel adds to Kant’s idea a few decades later with the assertion that “even a useless notion that enters a man’s head is to be more highly regarded than any product of nature.”

By the turn of the 20th century, the ideas of the Enlightenment became prevalent at Western universities. As the First World War began in 1914, the atonal composer, Arnold Schönberg, writes about his colleagues Bizet, Ravel and Stravinsky:

Now comes the reckoning! Now we will throw these mediocre kitschmongers into slavery and teach them to venerate the German spirit and to worship the German God. — Arnold Schönberg, in a letter to Alma Mahler in 1914

In the matter of a lifetime, the German idealists left the Classical Tradition in ruins.

In the 1930s, the Soviet Union demolished many churches and temples in a witch hunt on religion.

In the postwar-era, the demolition wave reaches the rest of the world.

Destruction of Orthodox Church of St. Michael the Archangel, Kharkiv. Part of the USSR anti-religious campaign (1928–1941)

Sagerska Husen in Stockholm, Sweden. The photo on the left was taken in 1968 — the photo on the right was taken in 2009.

The Renaissance… was the intellectual result of the Aristotelean influence, the influence of Aristotle’s philosophy, which in effect destroyed the Middle Ages and broke the way for the Renaissance. But ever since then, while men, while the culture in general were achieving incredible progress, culminating in the 19th century, on the basis of that Aristotelean influence, the intellectuals, ever since Immanuel Kant were going progressively more and more against reason. The trend started of course before Kant, but I consider Kant the crucial destroyer and the crucial turning point. He was the philosopher who undercut the validity of reason. […] By declaring that what we perceive is only an illusion, created by some special kind of categories and forms of perceptions in our own mind. […] That any object which is perceived is thereby false. It was in effect an attack on the whole concept of consciousness, not only human consciousness, but any consciousness. It was the denial of the reality or the validity of our perceptions. — Ayn Rand, TV-interview at the University of Michigan (1961)

In a world which yet again has abandoned the Classical Tradition, there are still glimmers of hope. The American painter, Andrew Wyeth, lived and worked until his death in 2009, and has, along with Nerdrum, Ai Xuan and Antonio Lopez, inspired a generation of young painters across the continents.

A similar awakening is experienced within architecture in several European cities, but in order to recreate the Renaissance, one must look at the people and ideas that enabled the humanist project.

Andrew Wyeth’s “A Crow Flew By”

A painting by Ai Xuan

Returning to the Greeks

From the rigid “Egyptian” statues, the Greeks developed an unrestrained fluidity, which rarely has been mastered since. Canova, Bernini, and Michelangelo did all approach Hellenism, despite the lack of original sculptures.

The last 150 years, archeologists have found numerous Antique masterpieces, still not causing a development of the Greek ideal. Instead, the Classical Tradition has become victim to musealisation, a trend which Nerdrum has tried to reverse throughout his career. Lately, in hope of reconstructing ancient painting, he has brought elements from Greek sculptures directly into his own work.

The Greeks’ Influence on Nerdrum’s Work

In Homeric times, Peloponnese became the center of Zeus worship, and initiated the Olympic Games in 776 BC. The Archeological Museum in Olympia shows finds from the area, including the pediments of the Temple of Zeus, and two hellenistic wonders:

Praxiteles’Hermes and the Infant Dionysus, c. 4th century BC. The sculpture was discovered in 1877 in the ruins of the Temple of Hera, Olympia.

Nike by Paionios. Excavated at Olympia in 1875–76.

Paionios’ Nike, the goddess of victory, was made about 420 BC and resurrected after an excavation at Olympia in the late 1800s. The posture is mirrored in several of Nerdrum’s recent works, where the distortion of the figure is emphasized. While the other front foot rests, the hind foot is actively pushing, strengthening the movement in the almost stagnant posture. As in late classical sculpture groups, Nerdrum’s figures are transformed into a single organism. The scene is captured in a dramatic image where past and future fuse, and man remains, in a floating moment.

Sleepwalker (2012-13) by Odd Nerdrum.

The Shot (2010) by Odd Nerdrum

The project of the Greeks seems more and more to be concerned with the middle state of nature. The transition between men and gods in the mythological depictions is almost indistinguishable, which thus separates Hellenism from previous cultures. The sculptures of Ancient Greece usually reconcile in a common denominator, which characterizes all the painters that have been studied in this series of six articles. In Praxiteles’ Hermes figure, the head is almost measuring 1/8 of the body, to create the effect of a man who extends from the ground. Hermes, who has a son together with Aphrodite called Hermaphroditos, is seen in an elevated posture at the Archeological Museum in Olympia. The ambiguous anatomy is reflected in the face, which changes from smiling to a gloomy stare, from a different angle. Painters such as Leonardo, Titian, and Rembrandt have been preoccupied by ambiguity, which is seen in a large part of Greek depictions. Nerdrum has often depicted himself and others in his paintings, as androgynous.

Left: Praxiteles’ Hermes. Middle: White Hermaphrodite by Odd Nerdrum. Right: Androgynous Self Portrait by Odd Nerdrum.

History is like a deep breath. We breath in and out. The Renaissance was a long-awaited inhalation after the Middle Ages, and then another exhalation before Odd comes along after 100 years with Modernism, that is, if you include Naturalism. And then there’s finally another inhalation. — Öde S. Nerdrum, The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum (2018)

But the inevitable question needs to be addressed: from where did the Greeks receive all the great knowledge of sculpture and painting? What were the ancient ruins and artefacts from a great civilization in the days of Aglaophon and Polycleitos?

Except for the influence form the Egyptians, history tells us little about any preceding culture that had a major impact on Classical Greece.

However, if sensuous, contrapostic depictions of man as an elevated being is an outstanding invention by the Ancient Greeks, then Aristotle’s idea of imitation as the creator’s foremost quality, must be strongly reconsidered. Is the greatness of the old masters, after all, their originality… their ability to portray reality in their own personal way?

Conclusion

After the sudden collapse of the Bronze Age, around 1200 years BC, the Greeks find themselves in the period designated as the Dark Ages of Greece. Little is known about this period, but human depictions disappear from the vases, and is replaced by abstract decorations.

In the Archaic Period which comes afterwards, the Greeks develop the Classical Tradition, which hits the Mediterranean people like a lightning strike in the 5th century BC.

Compared to the awakening in Europe 500 years ago, the idea that the Golden Age of Greece occurred out of thin air is an unsatisfying explanation. But is it possible that the first Renaissance was not in Italy in the 1500s, but in Ancient Greece? Considering the small amount of 2500-year-old sculptures that have survived, then it is likely that almost anything significant, prior to the Hellenes, has been eradicated by contemporary iconoclasts. Perhaps some old busts from Egypt bear witness of a humanism prior to Antiquity, and our knowledge of past cultures.

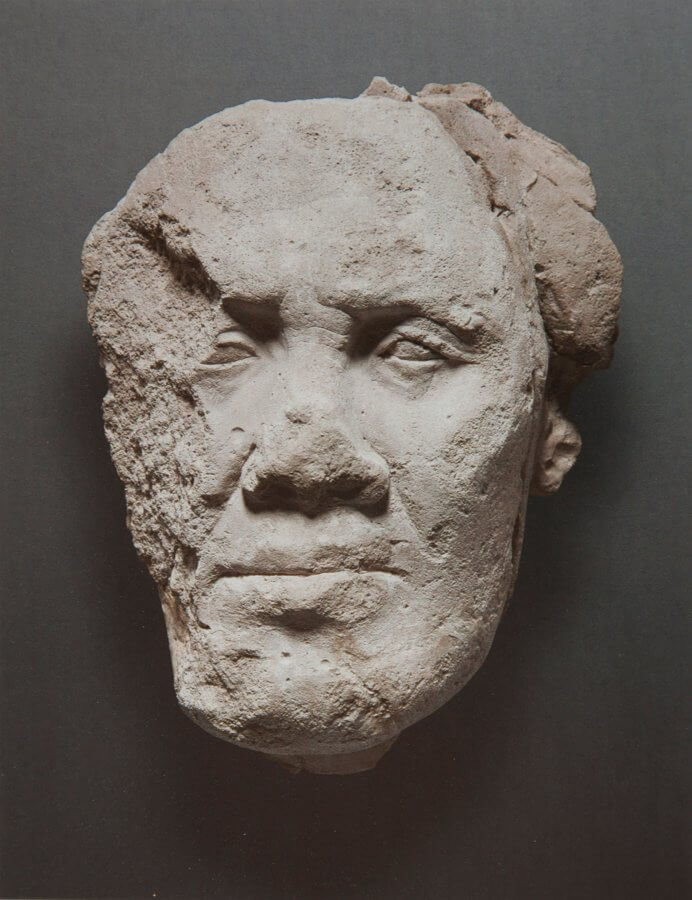

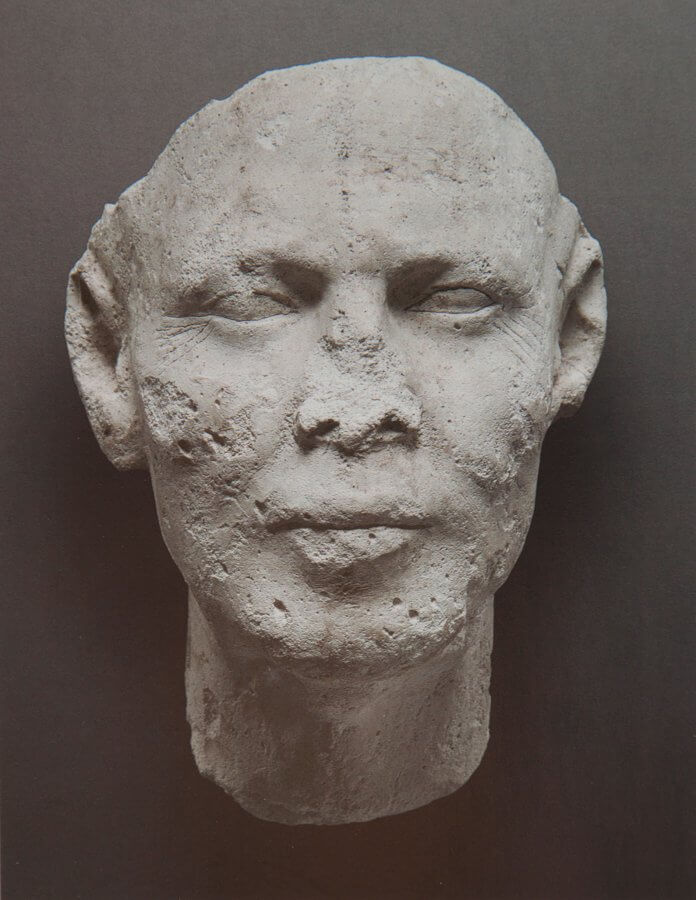

Model of a man from Amarna. Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin

Model of a man from Amarna. Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin

Is it possible that the ruins of the Amarna Period in the New Kingdom of Egypt, which flourished around 3000 years ago, are the reminiscences of a lost Atlantis, which goes even farther back in history…

Is it possible that all the golden ages of history are the results of great cultures of the past, that the Ancient Greeks will come again sometime in the future to overwhelm this world once more?

This is the last in a series of six articles based on “The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum” (2018) which is available for streaming at vimeo.com/ondemand/oddnerdrum. Read the previous article “Odd Nerdrum and ‘Pittura di Macchia.’

Members of WWK get 25% off any purchase. Send an e-mail to nerdrum.bork@gmail.com for more information.

The Hunt of Odd Nerdrum

Deciding to track down Odd Nerdrum’s sources of inspiration, his former pupil Jan-Ove Tuv and his son Öde go on a world tour, visiting the museums and people that crossed paths with the painter in his pursuit of the immortal masterpiece.

Genre: Documentary Duration: 4 h 26 min

Subtitles: English, Spanish and Chinese

Published on Sunday, July 8th, 2018