News and Articles › Gripping Film Moments

Life without Kitsch becomes unbearable.

— Friedensreich Hundertwasser, artist

Top list

View the entire list

Seasons and trends come and go.

Political opinions that were popular a 100 years ago are subject to the most anger and touchiness in 2016.

Regardless of people’s resolutions for the new year they will change according to the latest trend in society.

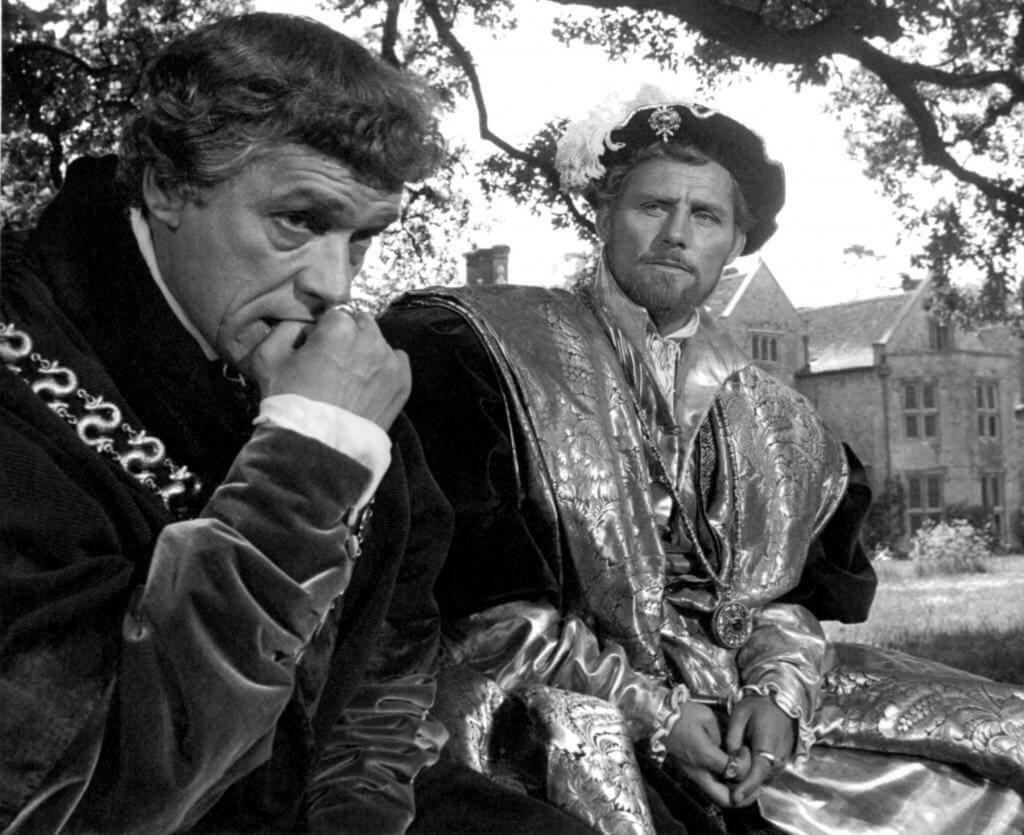

One man that will not do this – however – is Thomas More in A Man For All Seasons (1966).

Robert Bolt – who also wrote the screenplay for Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965) – explores the great dilemma of civilisation in his historical play about Henry VIII and Thomas More – which could be considered the best form of dialogue written since the days of Henrik Ibsen.

Viewed as a saint by Catholics and heavily denounced by others – Sir Thomas More is not exactly the ideal for a superhero-portrayal in a historical drama but that is exactly the genre Bolt chose and he did it well.

I have watched some of the scenes from this movie more than a twenty times and it never fails to entertain me. Every moment is filled with either witty remarks or philosophical pearls that will stick to your mind and always have relevance to your own life.

And on top of all this: the sequence of events are perfectly combined.

Structure Analysis

Opening – London. Cardinal Wolsey is writing a letter to Sir Thomas More. A messenger boy brings the letter by boat.

More’s home is lively and the discussion of the King’s marriage is openly discussed around the fireplace. More is summoned to Hampton Court by Wolsey to discuss matters of state.

Catalyst (9:50) – Cardinal Wolsey says to More: “The King wants a son – what are you going to do about it?”

Thesis (12:30) – Is More too principle minded to become the chief adviser of Henry VIII? Wolsey seems to have his doubts about his possible successor.

Debate (16:00) – Richard Rich is scraping at the doors of social power. Henry VIII desperately wants a male heir but in order to marry mistress Anne Boleyn he needs a blessing – to divorce Queen Catherine – by the Holy See of Rome.

Will Thomas More succeed Wolsey as Lord Chancellor of England and will he obey the wishes of breaking with Rome so that the King can remarry?

Antithesis (23:00) – The lawyer Sir Thomas More is officially handed the office of Lord Chancellor of England by his friend the 3rd Duke of Norfolk.

B Story (26:00) – The King arrives at More’s estate but leaves as soon as he understands that More does not want to bend the laws for the benefit of his own King.

Mid Point (46:00) – Hampton Court accepts the Act Of Succession which lets the King remarry and Thomas More gives up his position as Lord Chancellor. An excellent Point of no return!

Bad Guys Close In – Literally everyone attacks More because he by principle will not bend to the King’s marriage. His enemies tries to get him hanged – his friends leave him – even his family criticise him. He stands alone against the tides of change.

All Is Lost (111:00) – More is put behind bars in The Tower because he will not accept The Act of Succession.

Synthesis (120:00) – Everything is opposite of the antithesis. More’s family comes on a visit in his prison cell. He no longer holds the title as the most powerful statesman of England – even his wife and daughter are entitled to more rights than he does.

Since most things at this state have changed – More breaks down crying for the first time.

This scene is in many ways the kitschy moment everyone has been waiting for. The hero’s wit and “inhuman” courage is what we admire about him but it is the vulnerable side to his character that we truly revere. The breakdown of the hero completes the identification.

And no synthesis without a great showdown. More’s trial can be seen here:

You might ask why I analyse so many old movies.

But I would not consider anything neither old or new but rather good or bad.

When you study past masters you are more prone to see through the trends of their time than of those of your contemporaries’ and you will be able to pick out the quintessence of what they mastered.

Published on Saturday, December 31st, 2016